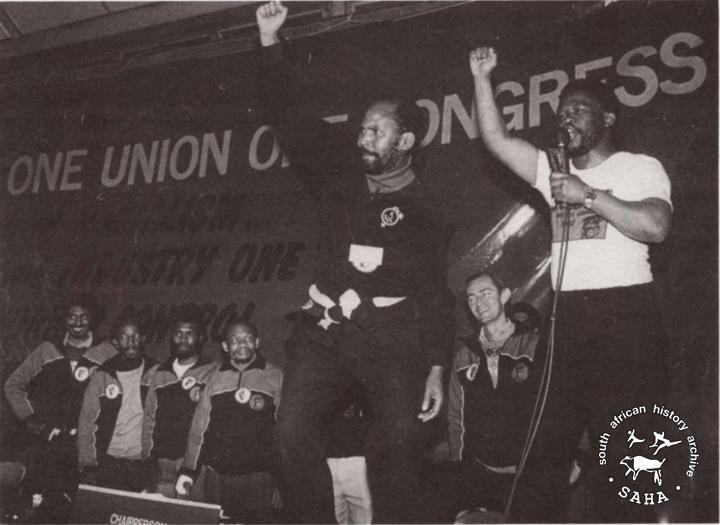

The end of 1985 saw the formation of the largest labour federation in the country's history, the Congress of South African Trade Unions.i Nonracialism was one of its founding principles and at its first annual conference COSATU formally adopted the Freedom Charter as its lodestar.

“If we pursue a racially exclusivist philosophy it will mean that we are not recognizing reality. What we say is workers require allies. If you look at it purely from a worker's point of view, from a purely tactical point of view, the idea is to strip the ruling class of all props that it has. Take the churches, for instance. The churches are a formidable force, having approximately sixteen million members. The vast majority are workers, peasants and so on, and therefore to exclude the church would be suicidal for the working class.

As a parallel, take the patriotic movement that developed during the last world war against Hitler and Mussolini — the forces were wide-ranging. The church played a very important role in those popular fronts. Monasteries, for instance, were used to store arms. And in Nicaragua the clergy actually sat in the cabinet, for you had a popular front government in power. So for the working class at this stage to suggest that they want to be exclusivist and espouse a pure workerist lineii, it would be just simply not adresing themselves to reality.

The ruling class actually wants allies desperately — hence the tricameral parliament and so on — and they succeeded in getting only a small segment of that middle class. Our approach is more scientific. The very shifts that are taking place in ruling class circles are indicative of the correctness of our line, the non-racial policies we are espousing.

Do you believe that non -racialism can best be achieved at the workplace?

No. You may have a tentative non-racial thing for eight hours a day, but this is mitigated by the fact that you are in a wider racial set-up, so unless you actually smash the wider prison in which the workers are engulfed, you are not going to have real non-racialism. Unless there's an across-the-board solution to our problems, any piecemeal solutions at the factory floor are not really going to answer the problem. Those concessions that the ruling class makes simply evaporate unless you have a broader democracy to protect those hard-won rights of the workers.

Now this is the challenge that the workers face, and this was the problem that SACTU faced in the '50s and '60s: do they, in the face of repression, say, 'Look, we have to preserve our hard-won rights and not engage the enemy until we are ready for it?' The question then arises: when would you be ready, if you're not prepared to engage them on a day-to-day basis? The workers cannot extricate themselves from the community, because they are part of it.”

BILLY NAIR, a former SACTU organizer who spent twenty years on Robben Island for Umkhonto we Sizwe activities, and upon his release was elected to the Natal UDF executive, working closely with COSATU

“Do the domestic workers you deal with really care about non-racialism?

I'll tell you something: our people never have any hatred. That should be understood clearly. The only thing they've got is a problem that the whites don't pay them well. But we also come out clearly on the fact that the Africans who employ domestic workers also don't pay them well. Now we discuss along those lines: those Africans, are they not exploiting us too? The workers' understanding of non-racialism is that we cannot do away with whites simply because they've got more experience on jobs than we Africans. Even if there are whites who maybe refuse to agree with us now, it's a reality of our country that we cannot afford to lose them.”

SHASHA MEREYOTLHE, an organizer for the South African Domestic Workers Union (SADWU), a COSATU affiliate

“At the first NUM congress we debated the question of a clause in the constitution — whether we would like to say 'black workers' or 'all workers' — and there was an overwhelming rejection of 'black workers'. The feeling was that if a white worker who renounced the apartheid system wanted to be a member, his application could be considered.

What do you think is the source of that commitment to non-racialism on the part of black workers?

It's very difficult to answer the question: where did they get that from when they are working in such an oppressive and racialistic environment? What came out from our congress was that the nature of the mines is such that the white person is only seen as an enemy because he's oppressing them and exploiting them. I remember at congress one man stood up and said that, 'We are going to re-educate those whites because they are workers like us. They are just being used and they need to come to a realization that they are being used.'”

CYRIL RAMAPHOSA, General-Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), South Africa's biggest and potentially most poweiful union

NUM's support for non-racialism was such that it pulled out of the Council of Unions of South Africa (CUSA), a Black Consciousnessioriented federation, and joined COSATU. CUSA and another small BC grouping, the Azanian Council of Trade Unions (AZACTU), refused to join COSATU because of its explicit support for non-racialism. The National Council of Trade Unions (NACTU), the labour federation formed through a merger of CUSA and AZACTU, pledged its support instead to the principles of 'anti-racism' and 'black working class leadership'.iii

“In my first union, the Food and Beverage Workers Union affiliated to CUSA, I was trying to push for a direction that will be pro the national liberation movement, especially the ANC. But when COSATU was formed and CUSA did not agree to be part of that, I had no choice but to move towards COSATU.

Non-racialism is a very important issue, one of the basic issues. You can't talk of class consciousness if you don't have a base for it, which will be a non-racial society. It's a non-issue if you already have class consciousness. That's why the ANC is talking about African leadership — it's not in a narrow sense, but we need to see our black people, who are the majority, coming up. And only then, when they are actually holding the bull by the horn, then one will know that one will be going somewhere. We mean that they are the lower stratum of the oppressed, so if they shake, the whole pyramid is shaking.

Was COSATU wise to refuse to compromise its non-racial stance at the time of its formation? Would it not have been more expedient to concede on non-racialism and accept other ideologies as well, thereby gaining COSATU greater membership?

Look, after discussing the difference between 'non-racialism' and 'antiracism', finally it was agreed that okay, let's embrace them both — we will say one of our objectives is 'non-racialism/anti-racism'. So there was a compromise. But still CUSA and AZACTU pulled out. So it means they were not sincere. When unity was achievable they wanted a pretext of running away, because they realized that its achievement will mean losing some of their personal gains. So it's not really a question of a compromise — it's a question of dedication, commitment and honesty.”

PULE THATE, who served five years in prison for ANC activities, and after his release in 1981 became a factory shop steward

“In NACTU we believe in a non-racial future, but first we accept the status quo. The land belongs to the indigenous masses — that must be accepted. Secondly, we believe that the colour of a person should not be the issue. Look at the Pan-Africanist Congress approach of saying that you recognize the human race, irrespective of the colour of the person. If you accept that you pay allegiance to Azania, then you'll be part and parcel of that country. The Africanist approach is that first they are looking at themselves as the African people who belong to the African continent, without saying are you black, white, whatever.

The Freedom Charter says the land belongs to everybody — I mean, that's totally wrong because the land should belong to the people of the country, the indigenous masses. I can't go to America today and claim part of the land. Now if you take the arrival of the settlers — that is, the white people in South Africa — to say that those people actually now are part and parcel of our country, it's a distortion of history. The black people are the owners of the land.

By black people, do you mean only Africans, and not Indians or coloured people?

I would say it's people who are black like myself, and coloured people. The coloured people are the people of Africa because they emanate from Africa.

Where do Indians fit in?

I'm not leaving them out altogether — if an Indian accepts that he should not be called an Indian, he should be called an African.

And if a white person says, ‘I see myself as an African'?

I think it's a question of a person himself accepting where does he belong. Maybe on the political scene I might not be able to give a clarity, because I'm not a politician, I'm a worker.

If you take a black personnel manager and a black worker, would you say both of them are Africans so they're both with you in the struggle?

Yes, they will be together, there's no difference. The division that will come in, it's purely in terms of practicalities, because one has got certain privileges. But it doesn't necessarily mean that he's totally being dissociated from the masses.

What is your view of white involvement in the trade union movement?

We don't recognize a question of colour within our federation. We are saying that every person who accepts that he's a worker is welcome. But for us to go out and appoint or employ a white and say he's a general-secretary,--that will not do because it's something that has been imposed by the leadership.

White manipulation has its history in our struggle and I reject that hidden agenda: it's the control of the black people's struggle. In actual fact those people are neutralizing the militancy of the people. The SACP, it is there within the ANC with its own purpose. It's a question of trying to implement Russian policies in our country — which we will not accept. Because immediately we involve a superpower, then the other superpower will try and come in and destabilize, and that's exactly what is happening in countries like Ethiopia, Angola, and Mozambique.

So what is your advice to whites who want to fight apartheid?

I think they should mobilize their own white community, whilst the blacks are mobilizing themselves. They've got leverage because they've got voting power — they can change the status quo within that. Basically there would be no development on the part of a black man if there is a white man in our organizations — so it is to safeguard, and to try and promote that development, self-confidence, self-determination, that we promote black organizations.”

JAMES MNDAWENI, a former CUSA leader who was elected NACTU president

This 1940s-style Africanist position eclipsed 1970s-style Black Consciousness as the dominant tendency within NACTU. In 1987, NACTU's leadership met with the PAC in Dar es Salaam and emerged with a joint statement of mutual support, giving rise to claims of a revival of Africanism in the trade unions. These were soon discredited, however, by evidence that NACTU's strength had been greatly exaggerated. With the disclosure that COSATU's members outnumbered NACTU's by more than five to one, it became apparent that the critics of non-racialism represented a minority view. In 1988, NACTU met in Harare with SACTU and the ANC, concluding in a joint communique that 'unity in action is a prerequisite for the quick defeat of apartheid'. Soon thereafter COSATU launched a policy of conciliation, stressing the need for cooperation between the two labour federations.

The ugly head of disunity, a cancerous leadership disease of the '80s, has received another death blow in the last six weeks. NACTU, after a historic meeting with the PAC in Tanzania in October 1987, took the next step on the road to worker unity by talking to the ANC in Zimbabwe. The main issue was the need for unity in action within the labour movement. In explaining the basis of unity, it was agreed that the Freedom Charter was not a prerequisite for unity. Further, that all legitimate organizations of whatever persuasion have a meaningful role to play in the national liberation struggle. To support this, ANC National Executive member and SACTU General- Secretary John Nkadimeng said, 'Certain people think it is a prerequisite that anyone who wants to join the new united front must support the Freedom Charter. We say this is incorrect.' Asked if this meant that the ANC believed groups like AZAPO and NACTU, who counterpose the Freedom Charter with the Azanian Manifesto, should cooperate with COSATU and UDF, who have adopted the Charter, Nkadimeng said, 'Yes, that is exactly what the united front stands for.' Nkadimeng claimed that the front is something that brings people together to fight a common enemy. This does not mean that they agree one hundred per cent with each other. These developments have no doubt been welcomed by all serious and mature militants in the liberation movement.

`United Front: Fight vs. Common Enemy, Solidarity: Voice of the Cape Action League, June 1988

COSATU could afford to make concessions over non-racialism in theory because of its substantial gains when it came to non-racialism in practice. An important index of COSATU's non-racialism was the unwavering support of its predominantly African membership for an Indian as its general-secretary.

“It is very important that non-racialism, as a concept, was built up by SACTU and by the other Congress parties. It was an important principle really defended by workers — even though that principle is constantly being broken by whites, even though other race groups are treating African workers like pieces of garbage. But workers still defend non-racialism.

But I don't think we can disguise the fact that there are tensions between Indian and African, African and coloured, Indian and coloured, between the different groupings within the African community itself. On the factory floor there are differences between Indian and African workers. There's a lot of suspicions as well, and it's a long struggle to overcome that.

There was very strong solidarity in the '50s between Indian and African workers. In the '60s, through the manoeuvring of the state and capital, divisions started to appear: one, by separation of the communities by the Group Areas Act, secondly, by promoting Indians to more skilled positions. And that created tensions. So overcoming those tensions at one level, and overcoming the fact that people are staying in separate areas, has been a long and difficult struggle, and is still a big problem for us, even today.

In the garment and clothing factoriesvi ,where it's the most substantial concentration of Indian workers, though they were very, very militant in the '40s and the '50s, in the '60s and '70s the unions catering broadly for Indian workers became very bureaucratic, very much benefit societies, and the perception of Indian workers started to change. So that if you talk to Indian workers who are in these unions you have an enormous problem, because their first question is, 'What benefits do you have?'

With African workers it's a question of an organization that is militant, that is able to mobilize workers, that's able to win things in the factory — not a question of benefits. With Indian workers, it's whether you have a doctor, do you have funeral benefits? Because this is what they've become accustomed to. And it's a big battle to break through those barriers.

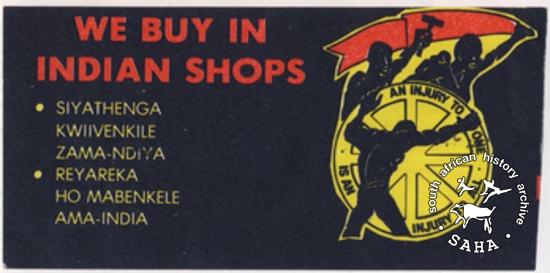

In strike situations you would have Indian workers coming under very much more pressure than African workers from management to scab. Like what happened with the tricameral parliament: even though the majority of Indian and coloured people boycotted, the manipulation of those collaborators was played up very much by the press and the TV and so forth. So for African people, they don't look at the fact that eighty per cent of the community boycotted, they look at the fact that there's people there who are selling us out. Although the majority of the Indian community are workers, the problem that we have now is that the exposure of African people to Indian people is through the traders, so their perception is of a group where every Indian person is a trader — which is a is understanding”

JAY NAIDOO, COSATU General-Secretary since the founding of the federation

At present, Indian workers are employed increasingly in skilled, supervisory and clerical jobs. But in many industries and many factories there are large enough numbers of Indian workers in production to prevent unity when they don't join up with African workers. Management tries to win over Indian workers through offering promotions, perks like loans, and through trying to keep a friendly, patronizing relationship. The bosses' actions encourage workers to see each other in racial terms. When Indian workers don't join unions or become involved in strikes, African workers see Indian workers as a problem. This increases the distance already existing between Indian and African workers.

But in many cases where Indian workers have joined, they are strong union members and have helped to organize other Indian workers. What these workers have come to see is that Indian workers can't get any improvements for themselves using the old ways of keeping in the bosses' good books, taking samoosas and biryani for the boss and so on. The Indian workers are in the minority and the only way they can win any real improvements for themselves is by joining with the African workers in the strong, fighting unions.

COSATU sees that the struggle of workers can be won only through unity among all workers, and by linking up factory struggles with community and political struggles. One of the main tasks of this new federation is to fight the divisions that exist amongst workers of South Africa and to unite them into a strong and confident working class. In the words of an organizer: For Indian workers the choice is clear. A ham :u1 have the option of standing with the bosses as managers and foreman against the workers and their unions. But for the majority, a better life can be won only through strong organizations in the factory and in the community.'

Divide and Profit: Indian Workers in Natal, Worker Resistance and Culture Publications booklet, Shamim Marie, 1986

“Another indication of workers' support for non-racialism is their acceptance of white union officials. Whites had focussed on shop-floor struggles in resuscitating the dormant labour movement in the 1970s; by the 1980s, some whites found another role, in building a community support base for a new brand of militant mass-based trade unionism. `Community unions' like the embattled South African Allied Workers Union (SAAWU) in the Eastern Cape encouraged their members to support township political structures, thus linking up community and workplace issues.

Although academically I'd done a lot of work on industrial relations, it was very, very different going into a union office. I remember one of the first meetings I attended, a lot of the workers were a bit surprised to see a white guy there — it was quite clear from the way in which they looked at me as they walked into the room and kind of gave me a sideways glance. Later on when we sang the songs and shouted amandlas, there was a different kind of response: you know, `You're really welcome amongst us!' In a way, it's as much of a problem, because until people start treating you normally, you can't actually properly do work with people.

Another problem was that management, in negotiations, they'd address a lot of what they say to me. I suppose they find it easier to talk to a white person than they do to a black person. You have to do things actively to break that down: I'd have to just keep quiet and not say anything, and they would just have to talk to the other union officials.

Why do you think it is that most whites who joined the trade unions first got involved with FOSATU, and not the community unions which later aligned with the UDF?

Well, let me go back a bit. In the early '70s, a lot of white students and university lecturers were involved in helping to set up trade unions, people who came from a background which intellectually stressed the fact that it was really important to organize workers. The broader political climate in the early '70s was also slightly different: there wasn't the kind of contact between civic groups, youth groups and trade unions that emerged in the '80s.

At the same time, a lot of those white people had just walked from a fairly academic environment straight into setting up trade unions, and they didn't want to mix political issues with trade union issues — basically because they felt the union movement couldn't survive if it got involved in political issues. Whereas in what eventually became the UDF-aligned unions, there was a much greater focus on linking up to the broader struggle.

Sometimes our people made a lot of mistakes on a basic sort of trade union level, because people were so involved in a whole range of political commitments it was difficult to spend the amount of time that was necessary to just build up the union side. On the FOSATU side it was quite clear that you had a very strong base, a fairly large number of ordinary workers taking charge of things in their own workplace, who were being influenced to remain distant from the broader political struggle. The politically active trade unionists' perception of whites in the FOSATU unions was that they were pushing for a direction that was anti the ANC and the tradition that that represented, and anti-SACTU.

Now I happened to be one of the few whites who went into the non-FOSATU unions. There was always the problem that you had to be very careful of the type of role you played, as one, an intellectual, but two, just a white person who comes out of an environment where you have a lot more skills and education — which would enable me to do things, like hire a car or find a venue in town. Now I saw that happening in the FOSATU unions. Whites were elected general-secretaries, and the reason was basically because it's easier to just put somebody in who's got those skills than to try and train somebody else who hasn't. There was a big stress on non-racialism, so it seemed to be quite a progressive thing, but I think in the long run it's a problem to just absorb whites in and to dump them in those kinds of positions, because it actually blocks the growth of other people, it divides the organization. And that meant we would fall back into exactly the same kinds of tensions that had emerged within NUSAS at the time when SASO broke away.

So I didn't think that non-racialism was a kind of unproblematic, treat everybody- as-equals business — it wasn't that at all. We were working in a situation where there were big inequalities, where there was a developing political struggle, which quite clearly had to ensure that ordinary grassroots people were actually being trained to take on the whole range of tasks. So I think it's going to remain a big problem because, despite the fact that whites are and should be accepted as full citizens of a liberated South Africa, the reality is that we've got to overcome a whole process in which whites still are dominant, in terms of the kinds of skills that they have, the sort of background, the educational opportunities.”

MIKE ROUSSOS, who worked in SAAWU and other community unions from the early 1980s, and in 1987 became national organizer and then education secretary for a revived SACTU affiliate, the South African Railways and Harbour Union (SARWHU), as well as a member of the COSATU Central Executive Committee

By the 1990s, there were far fewer white officials in the progressive unions than there had been in the 1970s: the intervening decade had produced more black worker leaders. As for white union members, their numbers were tiny, but the fact that there were any at all represented a significant gain for non-racialism.

We speak about our commitment to non-racial, working class unity. But can we honestly make any progress among white workers? Consider recent developments. In militant struggles black workers make gains despite the difficult times, while collaborating white unions lose ground. True, white workers still earn far more than blacks. But the wage gap is narrowing. It is no longer just black workers but whites, too, who increasingly feel the effects of the economic crisis.

White workers are a fairly small and decreasing section of the working class. But they have a strategic importance because of their economic position and place within the white bloc. In earlier periods, some white workers developed traditions of non-racial class struggle. Today they have generally been corrupted and confused by racial privileges over many decades. But the situation is beginning to change again. White workers now realize the regime is more concerned to please big capital than them?ix This sense of betrayal is used by the ultra-right to make gains at the expense of the NP [National Party]. But is this recruitment of white workers by the ultra-right inevitable?

The contact of growing numbers of white workers with COSATU unions shows it is not. In fact, we ourselves can begin to win over sections of white workers to more progressive positions. But this requires a clear strategy. Any significant headway will be made in the first place by appealing to white workers' growing sense of economic hardship. Moral appeals to non-racial justice or equality will almost certainly fail at this point.

Existing progressive organizations in the white sector are not well equipped to address white workers. The progressive trade union movement is better equipped for beginning to approach white workers. This in turn means addressing the understandable doubts of black workers who daily confront white workers as supervisors, racist bullies and strike-breakers.

Above all, we must remember the strategic possibilities in winning over white workers. One example: imagine the confusion of Afrikaans-speaking riot police, themselves from working class backgrounds, finding not just blacks, but their own brothers and sisters on a picket line or in a factory sit-in!

Can We Win Over White Workers?; Umsebenzi: Voice of the SACP, Fourth Quarter, 1988.

It was the government's escalating attacks on unions toward the end of the decade that deepened the spirit of cooperation in the labour movement. In 1989 COSATU called a Workers' Summit where all workers — and no union officials — were invited to speak. Members of eleven NACTU unions defied their executive's decision not to attend and sent representatives to meet with their counterparts in COSATUviii — a rebellion in the ranks that took the NACTU leadership by surprise. The message from NACTU's workers was clear: opposition to non-racialism was not seen as an uncompromising point of principle, even by those with a Black Consciousness or Africanist background. In the drive toward worker unity, support for non-racialism was accepted as the dominant trend.

There are many things which have kept us apart, but our very coming together is a powerful statement that our differences are nothing compared to our commitment to the principle of working class unity. As unions, we cannot deny the fact that the actions by management affect all workers. Issues facing all sectors demonstrate clearly the need for workers to act jointly to defend and advance our interests. It is this drive for unity among rank-and-file workers everywhere that has brought us to the summit, which represents an important consolidation of the labour movement.ix

COSATU President ELIJAH BAYARI, convening the first Workers' Summit in Johannesburg to protest against new labour legislation, 4 March 1989.

This transcendence of ideological differences extended beyond the trade unions. COSATU and the UDF joined with church leaders and Black Consciousness supporters in convening an historic 'all-in' conference to round off the decade. Invitations were extended to all groups that endorsed the 'Unifying Perspective.

All organizations committed to the reunification of our country and a democratically constituted government and adhering to the unifying perspective are invited to the conference.Unifying Perspective:x

• One person, one vote in a democratic country

• The lifting of the State of Emergency

• Unconditional release of all political prisoners

• Unbanning of all political organizations

• Freedom of association and expression

• Press freedom

• Living wage for all

Call by the convening committee of the Conference for a Democratic Future, November 1989.

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 22 AS A PDF

NOTES

i At its foundation COSATU comprised 33 affiliates, including the eight affiliates of FOSATU (which dissolved) and the other independent unions, with 500,000 signed-up members and 450,000 paid-up members. By the end of the decade its strength had more than doubled.

ii An approach that argues for exclusive working-class organization and political mobilization, i.e. that workers should give priority to building a solely worker-controlled trade union movement, which when strong enough should assume an independent, leading and directing role in the struggle against apartheid. This philosophy is generally opposed to broad alliances, and to workers taking up community and political issues.

iii While the merger was effected in late 1986, CUSA-AZACTU was not renamed NACTU until the next year.

iv At its 1988 conference NACTU conceded that the membership figures routinely quoted by the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) were greatly overstated, and released a new national paid-up membership total of less than 150,000 (as opposed to COSATU's more than 750,000). The lower figure also reflected a decline in support for NACTU's BC-oriented affiliates.

v SACTU had operated from exile since the 1960s.

vi The South African Clothing and Textile Workers Union (SACTWU), formed in 1989, was the first COSATU affiliate to unite large numbers of coloured, Indian and African workers.

vii The crisis in profit rates due to black labour militancy motivated big capital to push the state for concessions to reform apartheid — at the expense of white workers. The waning influence of the white working class also stemmed from demographic factors: lower white birth rates, emigration of white professionals, and decreasing European immigration.

viii The NACTU leadership had responded similarly to the October 1988 all-in Anti-Apartheid Conference, which was banned by the government. In interviews with South African Review: 5 (Ravan Press/South Mrican Research Service, 1989), Africanist leaders conceded 'a reluctance to risk diluting this one source of strength (NACTU) — which would certainly occur if unity developed with the far more powerful COSATU'. By the time of the August 1989 Workers' Summit, held to map a response to the white, coloured and Indian parliamentary elections, NACTU was working closely with COSATU.

ix A smear pamphlet allegedly issued by the (non-existent) 'Concerned Workers Association of South Africa' in the Western Cape in early 1989 bemoaned the union unity moves: 'We have no room for leaders like Mndaweni who changes like a chameleon overnight and listens to the ANC.' Another apparent indication of the government's antagonism towards NACTU's rapprochement with COSATU came with another fake document: a letter claiming to be from the PAC (though the PAC Harare office denied any knowledge of it) posted to NACTU shortly before the first Workers' Summit, urging its affiliates to resist attempts by the ANC to co-opt them.

x The conference traced its origins back to a resolution taken by delegates at a UDF National Working Committee conference in May 1987, leading to a planned Anti-Apartheid Conference in September 1988 which the government banned.