By the beginning of the 1990s, the broad front had never been broader. Sections of society that had long been firmly anchored within the ruling bloc were dislodged and engaged in mass actions against the state. In this period the struggle for a non-racial, democratic South Africa entered a new phase.

These gains came at a cost: half a decade of unprecedented warfare between the people and the state. Yet the commitment to a non-racial democratic future is now even more deeply embedded in South African history. The fervent defence of non-racialism by the latest generation of activists is a powerful sign that non-racialism will flourish in the future.

The largest and most potent new UDF affiliate was launched in early 1987, in total secrecy at the height of the State of Emergency — the first national youth movement since the ANC Youth League. Recalling the Youth League 'Class of '44', which included Mandela, Tambo and Sisulu, the South African Youth Congress leadership was dubbed the `Class of '87'. Four decades after the Youth Leaguers opened the debate on non-racialism, SAYCO closed it, by pledging its two million supportersi to uphold the non-racial principles of the Freedom Charter.

How and why did SAYCO adopt the Freedom Charter? SAYCO was formed on the basis of the existence of youth organizations in local townships and villages. Many of these local youth congresses had already adopted the Freedom Charter. The youth have always been in the forefront, the most radical elements within the UDF.

The other factor is that SAYCO arose after COSAS, which adopted the Freedom Charter and non-racialism from its inception. This idea of non-racialism was implanted in the youth congresses and taken up by our youth. When COSAS was formed, non-racialism and the non-racial approach to the struggle made a breakthrough. This was similar to the breakthrough in 1955 when the Freedom Charter was adopted. In 1956, when the Charter was adopted — not by the Congress Alliance, but by the ANC in particular — non-racialism won over what we call narrow nationalism. But the banning of organizations suppressed the idea of non-racialism and brought up racial approaches again — until non-racialism made another breakthrough. So this informed the formation of SAYCO, as it did the youth congresses throughout the country. Every campaign, every action we take, is guided by our understanding of the Freedom Charter. All other documents, like the so-called Azanian Manifesto, could not compete with the Freedom Charter. Non-racialism triumphed over the racial point of view.

The Charter refers to the coloured people, the Indian people, the African community and the white community as 'national groups'. National groups have nothing to do with races, but they have everything to do with the divisions which exist in South Africa today, created by apartheid. They are the building blocks of the future South African nation that will be neither coloured, Indian, African or white — it will be one South African nation. We need to understand how each of these apartheid-differentiated national groups have come to lose their rights in history. This helps us not to gloss over these apartheid-created divisions by simply ignoring them in quasi-revolutionary sloganeering.

It is this understanding that has actually helped us to formulate clearly and unambiguously the only solution to these divisions, which is unity of our people as a people, irrespective of race, colour, creed and sex: non-racialism. In this respect, non-racialism is the only possible South African liberation scenario which calls for the complete destruction of racism and ethnicity, and which is derived from the realities of the South African situation itself.

`SAYCO speaks on the Charter, SASPU National publication on the Freedom Charter, 1987.ii

Within a year of its founding, SAYCO became one of seventeen anti-apartheid organizations banned by the government.iii Much of SAYCO's leadership was either detained or forced into exile, and youths accounted for 80 per cent of the thousands detained under the Emergency regulations.

“I was arrested at 3.30 in the morning. There were four whites and two black police and South African Defence Force personnel surrounding the house. When they came inside the house they asked me my name, and then I was beaten up for something like 45 minutes. I was beaten with fists, kicked, and hit with the butt of a gun.

I was then taken to an interrogation room at Tembisa Police Station and they started interrogating me, beating me up for something like five hours. They asked me if I know something about the African National Congress, and about the campaign which maybe the students' congress is planning, and again about others whom they can't find. When I refused to answer I was beaten and given electric shocks from handcuffs. All my comrades were released. I stood firm, preferring to die.

On the second day I was again given electric shocks. I was stripped and put in a rubber suit from head to foot. A dummy was put in my mouth so I could not scream. There was no air. They switched the plug on, my muscles pumping hard. I couldn't see anything. When they switched the plug off, they took the dummy out and said I should speak. When I refused, they put the dummy back and switched on again. After a long time they stopped. I was stripped and put into a refrigerated room, naked, for something like thirty minutes. Then they put me back in the electric shock suit and I was taken into another interrogation room. My hands, feet and head were tied around a pole, and bright searchlights turned on. I felt my mind go dead. I couldn't see. I was dizzy. I was beaten again for the whole day. I have scars on my right hip, in my head, and on my back. I cannot even read at this present juncture.

Did you become at all anti-white as a result of that treatment?iv

You'll find that even I can be tortured to such an extent that maybe I can be paralyzed, but I don't want to see South Africa only being the blacks there. I want to see South Africa with all races living there in peace and harmony. So that is why I'm not going to change my ideology.

People inside the township, they'll tell you straight that, 'Look, you say you want to drive the whites to the sea — where are our children today? Some are dead, some are in detention, some are in exile, some are in hiding. They are for an ideology of a non-racial democratic South Africa.' I mean, my parents were politicizing me, and what I know now is that I and my parents are following one ideology, which is the ideology of a non-racial society in South Africa.”

BURAS NHLABATI, student activist from Tembisa township, north of Johannesburg.

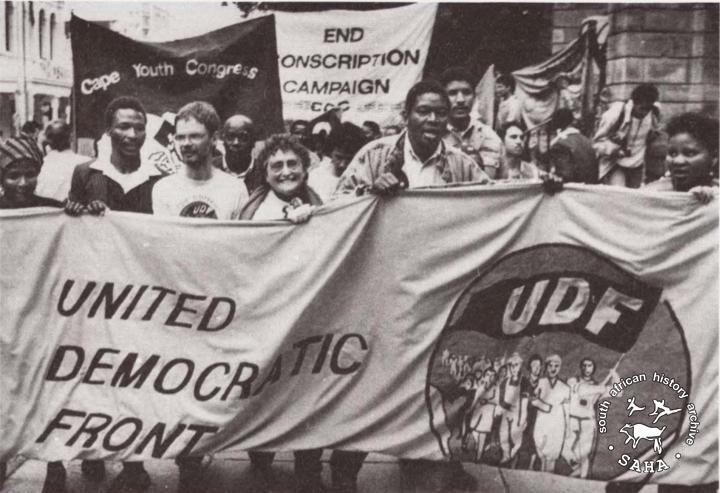

The ever-broadening struggle for a non-racial future, now known simply as the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM), gathered extraordinary momentum in 1989. A hunger strike organized in the prisons and supported by activists and professionals succeeded in freeing detainees. A Defiance Campaign brought the de facto unbanning of restricted people and organizations. Executions of political prisoners and censorship of the media decreased in response to unrelenting pressure. A local battle to desegregate a whites-only Johannesburg secondary school drew all races into a nation-wide open schools movement. In all these campaigns, non-racialism had never been more manifest, whether in the composition of crowds or the articulation of aims.

“There is a need to clarify what the MDM is: the MDM is a movement, not an organization. At its core is the strategic alliance between COSATU and the UDF. These are mass-based organizations based on sectoral lines: for example, youth, workers, students, women and civics. The core is committed to a unified ideological perspective, namely a commitment to non-racialism, democratic practices and grassroots accountability, the primacy of African leadership and leadership of the working class, and a commitment to the Freedom Charter.

The MDM also recognizes the centrality of the ANC in reaching any solution in the country, and we have a common position on negotiations. We are also united by a programme of mass action aimed at smashing apartheid and rebuilding South Africa along the lines of the Charter, and asserting socialism in the country. The ANC is the primary vehicle for building a non-racial, democratic and unitary South Africa. The releases of ANC leaders have sharpened this perspective and have created the conditions for building non-racialism. The people in this country are ready for a non-racial South Africa and we need to put a lot of energy into building non-racial sectoral organizations.”

JAY NAIDOO, COSATU.v

The wave of mass demonstrations in 1989 took popular protest out of the black townships and into the white city centres. Black and white protesters joined together in 'Open City Campaigns' in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, defying apartheid in residential areas, buses, hospitals, schools and beaches.

“You know, the struggle cannot be fought and won in the black townships. You have to fight in all areas of South Africa, and the white community must be involved in the struggle. You have to take them into the struggle and they must know there's a war going on in South Africa, because they're living a privileged life. They must be involved so that they know that there's a need for change. You know, it's not the African people who are going to fight and die for the liberation of the country alone. It belongs to all of us, and all of us must play a role either to liberate it or to keep it in bondage. But those who like to keep it in bondage must feel the pinch of the position they're taking. Once the struggle's waged across the country and crosses into white residential areas, people become aware. They don't only see it in their own TV screens at night when they're relaxed, you know. That is the point."

STEVE TSHWETE, ANC.

“The old argument was that if one does try to work in the white areas, one is trying to disorganize whites, to basically demoralize them and that was it. But whites have become much more querying, a lot more aware that the golden life cannot continue for all time. In many ways they are beginning to catch on the rebound some of the effects of the repression that they impose on blacks. Whites are actually feeling the war now. One is seeing the quality of life for whites, ironically, being affected by the privileges which they are being compelled to defend, and it's the price of defending them that's getting high. That's an interesting development, which makes for new possibilities.”

JEREMY CRONIN, SACP.

“I think that it's important that whites continue to generate ferment within white ranks, broadly. The kind of work being done by organizations in the white community actually means tremendous gains for our struggle, because democrats are being generated in that process, and unlike the force of events in the black community, it's actually far more difficult for whites in South Africa to come to terms with the reality.

At another level, I also think it is very important for us to take our ideas about current events into the white community. By way of example, I addressed students at Stellenbosch University. The meeting started with a lot of hostility — some forty or fifty rugger-buggers marched into the hall, completely kitted out in their rugby outfits, boots slung over their shoulders, placards, etc. I went there because I thought it was very important to be able to speak to these people. I understand the isolation that Afrikaners, especially, grow up with and live with for their entire lives. I understand the need to break through that. I also understand the counterrevolutionary role that people like that can play — not through any fault of their own, but because they haven't been exposed to any other ideas. My own experience at Stellenbosch illustrated this point very clearly.

You know, I was caught up in discussions there for two hours, long after the meeting had broken up. The people who remained to talk to me were the same rugger-buggers who marched in there intent on disrupting the meeting. They were asking very basic questions like, 'What would happen to us as whites if there were a take-over in this country? Are you going to chase us into the sea? What will happen to our language, Afrikaans?'

It is a difficult situation to read into, but we have to go in there to try and bring them over. We cannot allow an important section of South African society to be written off because of their birth or heritage. We have a political responsibility to present alternatives to them. I think in the longer term this will yield results by giving us the ability to stave off counterrevolution as well.

It's important to try and create as many schisms in the ruling bloc as possible. It's also important to lay the basis for a future non-racial South Africa. I do believe that whites, like everybody else, have made a contribution to South Africa, and that South Africa truly belongs to all who live in it.”

TREVOR MANUEL, UDF.

Disintegrating alliances within the ruling bloc offered another opportunity for intervention. Big capital was being forced to rethink its strategies, and the traditional alliance with white workers was redundant to its future plans. COSATU saw this as an opportunity to begin implementing a long-term strategy aimed at winning these workers into its ranks.

“I've studied the history of the working class here in South Africa, and I have actually noted periods where the white workers were revolutionary — until they were bought, bribed with privileges, job reservations and things like that, so that they will identify themselves with the ruling class rather than the working class. Now in terms of the national question — that of whites oppressing blacks — you start to understand that actually it's fear that makes the whites react in this way. Because they see themselves as a drop in an ocean, and they have that fear of the day this ocean will swamp them all and their identity will actually be lost. The whites need to be free, they need to be liberated from this fear.

I think the reason why we have actually taken a stand on this question is because we don't see this thing in a short-term period — we see it in the long term. In the long term the working-class struggle cannot be only black workers — it'll be workers in general, whether yellow, green or whatever. If we are really sincere about the working-class struggle, that the worker can only be free when he is the one who controls the political power and then he'll be able to change the economic policies, then of course the white workers come in. That is why we are presently engaged in the national democratic revolution, because before we move to socialism or anything like that, the workers themselves have to unite.”

THEMBA NXUMALO, COSATU.

The success of the broad front strategy suggested a tactic unthinkable only a short time ago: recruiting support from within the repressive arm of the state itself. Changing conditions inspired the confidence to venture into enemy territory. In late 1989 a coloured lieutenant won popular acclaim for denouncing police brutality, demonstrating how an enemy of the people could join the people's camp!vi A black former Security Policeman confessed to his involvement in the assassinations of political activists; then a white former police captain admitted he had commanded a secret military `death squad', fled the country, and announced that he had joined forces with the ANC.vii These unprecedented developments unfolded against a background of rising rural resistance. Demands for the reintegration of the homelands into a unitary non-racial South Africa and the rejection of `ethnic' separation sparked general strikes and coups throughout the homelands in early 1990.viii In one striking incident in the Bophuthatswana homeland, police burnt their uniforms to protest the killings of demonstrators at a peaceful rally.

You have been told that you are defending the people — but are you not living in shame, rejected and isolated by your own people? Haven't many of your colleagues and family perished at the hands of the oppressed people? You have been told that the racists are superior and invincible. But is the regime not starting to crumble, has it not failed to protect you? You can liberate yourself from this shameful life and become part of the people once more. Brother soldier, policeman: choose now before it's too late. You can and must join the fight for freedom:• Refuse to shoot your own people, point your guns at the enemies of freedom.

• Join the mass and armed actions of the people.

• Give information about enemy plans and actions.

• Take action against officers and commanders, sabotage equipment and logistics, disrupt transport, communications and energy.

You can and must become part of the organized fighting contingent.

Start now, take a small step forward: pass this leaflet on!

"Black Soldier, Policeman: Stop Killing Your Own People!", ANC pamphlet produced inside South Africa and distributed at the mass march on John Vorster Square Police Headquarters, Johannesburg, September 1989.

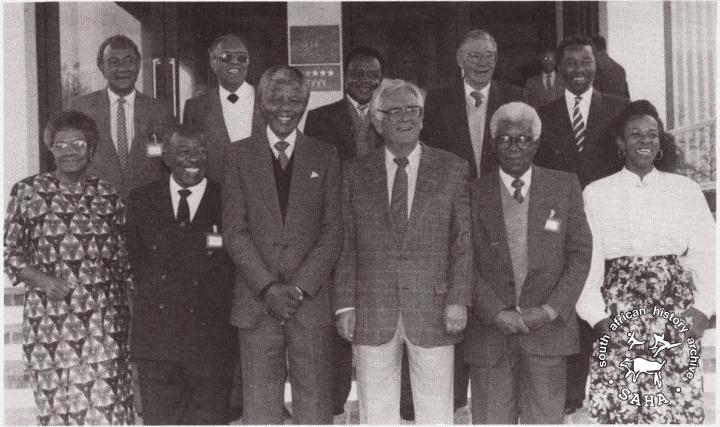

In February 1990, the South African government succumbed to political and economic pressure: President F. W. de Klerk unbanned the ANC, PAC and SACP and released Nelson Mandela. Blacks were jubilant. For whites — aside from the increasingly isolated right wing — initial shock turned to anxious optimism. The South African struggle had entered a new phase, marked by the first talks aimed at negotiating an end to white minority rule. The momentum was clearly irreversible: the long-cherished ideal of a non-racial democracy was shaping a new South Africa.

We are committed to building a single nation in our country. Our new nation will include blacks and whites, Zulus and Afrikaners, and speakers of every other language. ANC President-General Lutuli said, 'I personally believe that here in South Africa, with all of our diversities of colour and race, we will show the world a new pattern for democracy. I think that there is a challenge to us in South Africa, to set a new example for the world.' This is the challenge that we face today.

NELSON MANDELA, addressing a mass rally in Durban, 25 February 1990.

“We tend to refrain from engaging in predictions about the future, but what we do believe is that we prepare for the future in the present — and that is one of the big arguments why we believe that the non-racial approach to our struggle is quite important. We believe that the building of a new South Africa does not have to wait for liberation, whenever that will come, but the process has to be begun whilst we are engaged in struggle. The fact that we have white comrades who fight side by side with us, that builds and develops among us that commonness that we hope to see in a future South Africa.Many whites are withdrawing into their shells precisely because they have a fear of losing whatever privilege they have. And no doubt about it, there is no way an equitable society can come out of South Africa without a relinquishing of some of these privileges which most of the whites have — privileges which nobody could claim they have a legitimate right to be having. Now the question is, how does one do that without being insensitive or inconsiderate of people's views and feelings, or taking things away from people who should be having what they will say belongs to them?

For us to bring a new social system about in South Africa can't be done unless we actually tamper with those privileges. That is why when one looks at the Freedom Charter, on the clause that has to do with economy it talks of the nationalization of monopoly industries. That is something which addresses itself both to the question of imperial domination of foreign capital in the country and also to the fact that we need to develop our own national economy, which would also be able to sustain itself with its own initiative. So I think that, taking that into account, it would be an effort towards streamlining our production relations up to a point where we would be able to distribute equitably the resources that are there. We seek to develop a South Africanism that would, at the point of take-over, not give us problems of having to consider people on the basis of colour. And we have to begin building that now in struggle.”

MURPHY MOROBE, UDF.

“The point is that we're not simply fighting for non-racialism, because if you fight for non-racialism it becomes simply a civil rights struggle. Ours is a struggle for the seizure of power and its transference to a majority of the people. Non-racialism is a form that the struggle takes, but it is not the content of the struggle, it is not the objective. We're not simply fighting for non-racialism for non-racialism's sake — no, we are fighting to put an end to a situation which prevails where we are foreigners in our own land, where we have no votes and no say, no nothing, and we are simply beasts of burden for the benefit of a minority and the multi-national corporations. Non-racialism does not mean that the ethnic or the national question disappears. The fact of the matter is that there are these national cultural differences — non-racialism emphasises the fact that these are not fundamental. The fact that you are white or black is simply one of those accidents of history, which should not determine who runs the country or who gets what share of the national cake.

Will there be an effort to ensure black representation in the structures built after apartheid has been dismantled?ix

Yes, a total lack of discrimination on the basis of race is going to be meaningless if you're not going to do something in order to redress centuries of oppression. To say that the doors of learning will be opened to everybody is meaningless when people have no means of going to school or of buying books. It means you must create those conditions to make the doors really open and enable people to enjoy these benefits. You'd have to do something to redress that imbalance, otherwise apartheid is going to continue in reverse. It will be removed from the statute book, but it will remain if the economy still remains in white hands. So what you need to do in order to destroy apartheid is to destroy it as a political, social and economic system.”

MAX SISULU, ANC.

“People ask me what is it like being a white working for black freedom: 'What is a nice white person like you doing in a movement like that?' There was something about that question that just jolted me, something all wrong about it. But it made me think, well, what was I doing? I thought about it and thought about it and I thought, no, I had not been fighting for the black people — I had been fighting for myself. I had been fighting for the right to be a free person in a free country, and the only way that could be achieved would be through the liberation of the black people. And the reconstruction of South Africa.Nobody fights for somebody else. You participate in a cause, and there are lots of cultural problems and questions that have to be handled, and they are not easy and it never ends. It is not something you can say, well, now I am there, it's over.

Non-racialism is not just a bland thing. It is not just an absence of racism — that's empty. In fact, the reality of developing a non-racial culture in South Africa is much richer than that. It is much more active, more dynamic. It includes language, song, it includes dance, movement, it includes laughter, a way of telling a story, a way of making a political point. I enjoy seeing a way of working that maybe takes a little longer, but involves people much more. It has a richness, a strength. It is popular in the sense of being people-oriented, people-participatory.

I feel very enriched. I am gaining, I am not coming into a movement bringing left-wing political ideas which are then imposed on people. The people are grabbing those ideas, they are looking for an explanation of their country in terms of the world. They want to get out of this pure white-black, black-white thing. They want to shatter the limits that apartheid imposes, not simply on what you can do, but on what you can think.

I think a major achievement of the ANC leadership, the source of its great strength in recent years, has been to combine these cultural trends: the culture of resistance and the African culture. It's the talking things through. It's the patient way of involving everybody. It's a respect for every participant. It is looking at the people and knowing they have an immense variety of experiences and backgrounds, and some are Christians and some are anti-Christians and some are non-Christians and some are Moslems, and some have grown up in the ghettos in the cities and others are rural peasants — so all these cultural styles and traditions come in.

It is much more than non-racialism in that bland, neutral sense. Non-racialism doesn't mean that it is a society of `non'-something. It means you are eliminating all the apartheid barriers, in terms of access to government, in terms of freedom to move, and then you feel that this is your country. But it doesn't describe the quality and personality of the country and people. That is not a non-something — that is a something, and that is a South African personality that is being constructed.”

ALBIE SACHS, ANC.

“What I know is that being blacks alone, we can't reach our goal. The workers alone, they can't liberate our country. Students alone can't liberate our country. Women alone, they can't liberate our country. So you'll find that no party can just lead the struggle alone and liberate the country, but we shall go there to our liberation goal all being united.”

BURAS NHLABATI, SAYCO

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 24 AS A PDF

NOTES

iAt its launch, held clandestinely on 28 March 1987 in Cape Town after three last-minute changes of the venue, SAYCO claimed a signed-up membership of 600-700,000, with a support base of three times that, in 500 youth organizations all over the country. Its potential power was amplified through an alliance with COSATU, whose leadership welcomed the organization of the militant youth as the 'strongest, best and most reliable allies of the working class'. In a new departure for legal opposition politics, from its inception SAYCO operated underground. Nevertheless, its support and status in the townships continued to grow, participation of coloured and Indian youth was greater than ever before, and some of its affiliates even attracted white members.

iiThe South African Students Press Union (SASPU) is a NUSAS project to which the English-language universities' official student newspapers are affiliated; SASPU National is the national student publication.

iiiAll but two of the organizations banned on 24 February 1988 (AZAPO and the Azanian Youth Organization, AZAYO) were UDF affiliates.

ivThe first part of Nhlabati's comments is excerpted from his testimony to the International Conference on Children, Repression and the Law in Apartheid South Africa, 25 September 1987, Harare, Zimbabwe. With this question, the interview with the author begins.

vFrom 'Forward to Freedom: The Tasks After Victory', an interview in New Nation, 20-26 October 1989.

viLieutenant Gregory Rockman of the Mitchell's Plain police station founded the Police and Prisons Civil Rights Union (POPCRU) and laid a complaint that led to two senior riot control policemen being charged with assault. They were acquitted and Rockman was suspended, then fired from the police force in early 1990, while POPCRU led the first police and prison warders' protest strike in more than 70 years.

viiButana Nofomela was a death row prisoner when he made his confession in late 1989, naming Dirk Coetzee as the field commander of the secret unit responsible for the assassinations of, among others, Durban human rights lawyer Griffiths Mxenge in 1981, and Ruth First in 1982. Coetzee then confessed to the progressive Afrikaans newspaper, Vrye Weekblad, before fleeing the country. A judicial inquiry revealed that an elite military unit tasked with assassinations had been responsible for some 200 operations aimed at anti-apartheid figures outside South Africa.

viiiThe homeland governments of Ciskei and Venda were toppled in coups, while Gazankulu was paralyzed by a general strike.

ixEfforts to ensure this goal are often known as 'affirmative action', a term coined in the US in reference to policies implemented by government and other employers to hire certain quotas of ethnic 'minorities', i.e., African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, Native Americans, etc., as well as women and disabled people.