Although the Second World War was fought against fascism, few whites made the link between Nazi persecution of Jews in Europe and the oppression of blacks in their own country. The Army Education Service aimed to 'inculcate a liberal, tolerant attitude of mind'i to counter the considerable Nazi support in South Africaii, but the only effort to organize soldiers in a way that related their war experience to the situation back home came from a group called the Springbok Legion.

"We started what we called a Union of Soldiers. Then we heard about the Springbok Legion that had started almost simultaneously, from servicemen who for one reason or another found themselves back in South Africa, and from then onwards we were busy recruiting for the Springbok Legion. It became a vehicle in the South African Army for a lot of progressive thinking, on the race issue as well, amongst white South African soldiers.

You see, when you look at the problem of bringing the whites across, as an abstract theoretical thing you can see all sorts of bloody problems. But given the right climate, as existed, for instance, amongst soldiers during the war, we were able to do an enormous amount of work in a progressive direction amongst them. We took up all sorts of issues there - not only the question of increasing family allowances and things that were hitting their pockets and their families, but on political issues calling for sterner measures against the Broederbondiii and against the Ossewa Brandwag.iv We were able to do that sort of work.

Don't forget, the bulk of the South African Army were Afrikaners, not English-speaking, and they were also bloody fed up with this lot. Some of them were being beaten up when they went to their home towns and their doips [villages] by these anti-war elements. The Springbok Legion organized a huge demonstration in Johannesburg which smashed up a Nationalist Party conference, again with whites turning out in force; and a hell of a lot of Afrikaners and ex-servicemen. I remember one huge Afrikaner coming along there carrying a rope, and he says, 'If I put my hands on Malan5 I'm going to hang the bastard!' I mean, that was the strength of feeling that arose then against those they regarded as traitors, who tried to stab them in the back when they were fighting.

And one could see how, given the right circumstances, you can win political support from whites behind particular progressive demands. For instance, when the government was scared to arm the Africans and the coloureds and the Indians in the face of the opposition from the right-wing and the anti-war elements, amongst the soldiers you could get across the line that, look, why shouldn't they be armed? The question of making a maximum contribution to the war, let's get this bloody thing over. So you'd be bringing in the colour issue around concrete things.

Also, you know, soldiers being soldiers, going through Africa, Abyssinia [Ethiopia], and so forth and so on, a hell of a lot of white soldiers made contact with black women for the first time in their lives. The Immorality Act6 didn't apply as far as the soldiers were concerned, I can assure you - that's the last thing they thought about.

It's funny, you seldom heard any anti-black sentiment amongst the white soldiers. If you're in an army and a man's on your side, you respect him, you see. They saw people of different races fighting together on the same side against the common enemy. This couldn't but have an effect on their general thinking. How long it lasted after the war, I don't know, but I'm sure a hell of a lot of it stuck. I doubt if it would have been possible for any South African government, at that stage, to use the South African Army against the black people as they've been doing."

FRED CARNESON, who was amongst the first South African soldiers to see active service in 1939, serving in the North African and Italian campaigns

Only a minority of Springbok Legion members returned home from the war radically politicized, but of those who did, many developed a lifelong commitment to political change.vii

"I wasn't really that interested before the war, but once I got into the Springbok Legion, I felt I'm really doing some good here. Because after all, why should we go and fight and then come back and be treated like we were told the First World War soldiers were treated: the big heroes when the war was on, and then they came back to nothing?

That, in theory, together with what I actually saw with my own eyes, I thought, no, this can't be right, there's something wrong, you know - when I saw these people coming out of the hills, ragged, obviously poor people, and the richer ones were thriving and living in good houses that hadn't been touched. What I saw there in Italy I think probably politicized me even more than anything else. Because when we advanced on towns and cities, you couldn't help noticing that the places that were destroyed by air and so on were not the big, nice houses - it was always sort of the poor hovels.

There's no doubt about it, I'm absolutely certain that there was a policy of doing that type of thing - bombing the poor peasants rather than the wealthy. That had a terrific impact on me, because I equated these poor people with the coloured people that I knew lived in hovels and the Africans who lived in tin shanties that I knew and had seen in South Africa.

We had Afrikaners in the army and they made the connection - though not sympathetically. The way they treated those poor people in southern Italy, the working class types who were eating dogs and cats and everything, the Afrikaners said, 'Hulle is net soos ons kaffirs.' [They are just like our kaffirs.] And I thought, now these people are not black, and yet the Boers are saying they are like kaffirs. Then I started thinking and then I started reading.

The Springbok Legion were getting newsletters to us, and I had some books that I managed to get hold of - some were Marxist and some were on the subject of race. Wherever I went I'd be looking round for books and discussing with people who were in advance of me politically, and finding out what this was all about, you see. Finally I decided that now I was going to get involved in the movement, and if possible, full-time, to overcome this racialism, which was like poison.

After all, Hitler had been a racist against the Jews - he said he was going to do the same thing to the blacks. Here were the South African whites doing the same thing as Hitler said he would do - they were already doing it. And you know, it all came together and I thought, no, this is wrong, man, and I have to do my bit towards getting rid of it. I'd gone to meetings and it all fitted in with what was going on in my mind, and I knew that's where I belong - never mind about luxury and business and, you know, being rich."

WOLFIE KODESH, who joined the South African army after finishing high school, and was recruited to the Springbok Legion soon after its formation in 1941, while training in North Africa for the Allied offensive in Italy

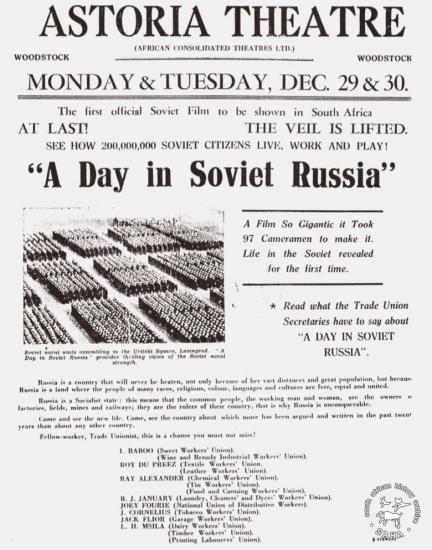

The entry of the Soviet Union into the war in 1941 opened up further opportunities for politicizing South Africans along non-racial lines, for the 'Red threat' was now 'our glorious ally'. Soon after the Soviet consulate opened in Pretoria in 1942, the Friends of the Soviet Union (FSU), a small anti-fascist group, was reinvigorated, receiving popular support from even government ministers.

The spirit of the East and the spirit of the West would soon meet across the stricken body of Nazi Germany, said the Minister of Finance, Mr. Hofmeyr, when he opened the Southern Africa-Soviet Friendship Congress before a large audience in the Great Hall of the University of the Witwatersrand last night. On the platform were members of the Diplomatic Corps and representatives of the Church, the Army, education, the trade unions and other aspects of public life. A message was read from the Prime Minister, General Smuts, in which he said the influence of the Soviet Union for peace would be immense, and much good could come from the continuous exchange of information among the United Nations in building up a more enlightened civilization.

'Meeting of Spirit of East with Spirit of West: Soviet Friendship Congress Opened in City', STAR, 7 July 1944

The Soviet Union's popularity also helped swell the ranks of the Communist Party in South Africa, its membership rising from hundreds to thousands during the war years. The CPSA's call for white members to join the army was instrumental to the founding of the Springbok Legion, and by 1942 the party was sponsoring 'Defend South Africa' rallies around the country. The government noted these displays of patriotism: after veteran white labour leader Bill Andrews was elected CPSA chairman in 1943, he was asked to broadcast a pro-war May Day message to workers on the government-run radio service.

For the first time since the 1920s, there was more than a token focus on recruiting whites to the CPSA. Communist candidates contested various elections in 1943, winning two seats on the Cape Town City Council and one on East London's, and the next year securing one on the Johannesburg council and two more in Cape Town.viiiThis outreach even extended to the launch by CPSA members of an Afrikaans-language newspaper.xi

"I would say up till the war years we didn't really get to the whites of the country. But from the time that the Soviet Union entered the war in 1941, there was this feeling of solidarity with the Soviet Union, so it really was an opportunity for the FSU to get to the whites, to put our point of view about the Soviet Union. Because there was so much literature coming in, for the first time the whites who knew nothing about the Soviet Union were able to find out more about what was happening there.

In telling people about the Soviet Union, you were popularizing the socialist system - which most whites knew nothing about. In fact, up till the time that the Soviet Union entered the war, Russia was something you fought against. Certainly during the war years, that accent changed. From becoming violently anti-communist, people became sympathetic to the Soviet Union and the Soviet system. We hoped that this would be an ongoing process, but after the war came the Cold War, and it was not so easy. After the end of the war, it was blacks that came into the FSU.

But a lot of whites remained, like the Jewish Workers' Club,x for instance. A lot of their members came from Eastern Europe and some came from the Soviet Union, and that organization certainly flourished during and after the war and did a lot to popularize the Soviet Union. And when they had meetings, if they could have blacks as well, they did have. And in that way there was again a mixing of black and white."

ESTHER BARSEL, a CPSA member active in the FSU in the 1940s and 1950s

Virtually all the considerable war-time political gains of the FSU and the CPSA were reversed by the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950. That law not only banned the Communist Party, but it unleashed a ruinous offensive against non-racial organizations. The militancy stoked by the Springbok Legion fizzled out, despite a spurt of activity in the early '50s led by an ex-servicemen's association called the Torch Commando.xi The Soviet Consulate in Pretoria was closed in 1956, although the South African Society for Peace and Friendship with the Soviet Union, as the FSU was renamed, staggered on until its banning in 1963.

Communists regrouped underground, later to resurface as the South African Communist Party (SACP). The abortive effort to woo whites had once again vindicated the view that the SACP's most viable base was among the black workers.

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 7 AS A PDF

NOTES

i In her interview for this book, Helen Joseph quotes this as a goal of the Education Service, in which she served as an Information Officer, along with Brian Bunting, Miriam Hepner and others.

ii There was considerable support among Nationalist Party ranks for the pro-German fascist movement, the Ossewa Brandwag (OB), 'Oxwagon Sentinel'. (The oxwagon used by nineteenth-century Boers to 'trek' from the Cape was a symbol of Afrikaner independence and resistance to British imperialism.)

Nationalist leaders tried to distance themselves from the OB, but several OB activists, including John Vorster, who became South Africa's prime minister in 1967, were interned during the war for their Nazi sympathies.

iii This Afrikaner nationalist body grew out of a group formed in 1918 called Jong Suid-Afrika (Young South Africa). The Broederbond ('Brotherhood') established its key public front, the Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurverenigings (Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Associations) in 1929, and then concentrated on building the right-wing cross-class alliance that won political power in 1948.

iv See note ii, above.

v D. F. Malan, a member of the pro-Nazi Ossewa Brandwag who successfully campaigned in the 1948 elections on a pro-apartheid ticket and became prime minister.

vi The Immorality Amendment Act of 1950 forbade extramarital sexual intercourse between whites and blacks, extending a 1927 law to include coloureds and Indians. The Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 prohibited marriages between whites and members of other races. Both laws were scrapped as a reformist concession in 1985.

vii Among those ex-Springbok Legion members who went on to play important roles in South African political organizations were Carneson, Kodesh, Joe Slovo, Jack Hodgson, Brian Bunting, Rusty Bernstein, Ivan Schermbrucker and Cecil Williams. Bram Fischer, Vernon Berrange and others joined the Legion's Home Front League.

viii The best-known CPSA election victory was that of Hilda Watts (now Bernstein) in the Johannesburg municipal poll. For more on the popularity of the CPSA in this period, see South African Communists Speak 1915- 1980, Inkululeko Publications, 1981. For a critique of the CPSA's war-time strategies, see 'Class Conflict, Communal Struggle and Patriotic Duty: the CPSA during the Second World War', Tom Lodge, African Studies Seminar Paper, University of the Witwatersrand, 1985.

ixDie Ware Republikein (The True Republican) was aimed at Afrikaner workers.

x Formed in the late 1920s, its support had waned by the time its Johannesburg office burned down in 1948.

xi Formed in 1951 by a small group of English-speaking white war veterans opposed to the government's unconstitutional plans for removing the coloureds from the voters' roll, the Torch Commando joined with the United Party and the Labour Party to form the 'United Democratic Front' in 1953, but faded from the scene after the Nationalist Party's re-election.