The practical experience that taught Congress Alliance members mostabout building non-racial unity was the organizing of the Congress of the People in June 1955, by a newly-created National Action Council (NAC) consisting of eight members from each of the four sponsoring bodies.

We call the people of South Africa, black and white — Let us speak together of freedom!

We call the farmers of the reserves and trust lands. Let us speak of the wideland, and the narrow strips on which we toil. Let us speak of brothers without land, and of children without schooling. Let us speak of taxes and of cattle,and of famine. Let us speak of freedom.

We call the miners of coal, gold and diamonds. Let us speak of the dark shafts, and the cold compounds far from our families. Let us speak of heavylabour and long hours, and of men sent home to die. Let us speak of rich masters and poor wages. Let us speak of freedom.

We call the workers of farms and forests. Let us speak of the rich foods we grow, and the laws that keep us poor. Let us speak of harsh treatment, and ofchildren and women forced to work. Let us speak of private prisons, and beatings and of passes. Let us speak of freedom.

We call the workers of factories and shops. Let us speak of the good things we make, and the bad conditions of our work. Let us speak of the many passes and the few jobs. Let us speak of foremen and of transport and of trade unions;of holidays and of houses. Let us speak of freedom.

We call the teachers, students and the preachers. Let us speak of the light that comes with learning, and the ways we are kept in darkness. Let us speak of great services we can render, and of the narrow ways that are open to us. Let us speak of laws, and government, and rights. Let us speak of freedom.

We call the housewives and the mothers. Let us speak of the fine children that we bear, and of their stunted lives. Let us speak of the many illnesses and deaths, and of the few clinics and schools. Let us speak of high prices and of shanty towns. Let us speak of freedom.

Let us speak together. All of us together — Africans and Europeans, Indian and Coloured. Voter and voteless. Privileged and rightless. The happy and the homeless.All the people of South Africa; of the towns and of the countryside.Let us speak together of freedom. And of the happiness that can come to men and women if they live in a land that is free. Let us speak together of freedom.And of how to get it for ourselves, and for our children. Let the voice of all the people be heard. And let the demands of all the people for the things that will make us free be recorded.

We call all the people of South Africa to prepare for the Congress of the People — where representatives of the people, everywhere in the land, will meet together in a great assembly, to discuss and adopt the Charter of Freedom.

This Call to the Congress of the People is addressed to all South Africans,European and Non-European. It is made by four bodies, speaking for the four sections of the people of South Africa: by the African National Congress, the South African Indian Congress, the Congress of Democrats,and the South African Coloured People's Organization.i

‘Call to the Congress of the People,’ NAC LEAFLET, 1954

When South Africa's first non-racial trade union coordinating body was formed, the South African Congress of Trade Unions became part of the Congress Alliance.

SACTU's members joined with the thousands of other Congress Volunteers in canvassing demands for the Freedom Charter.

The active involvement of SACTU in this and many other Congress campaigns derived from its belief that organizing workers is inextricably linked to engagement in the wider political struggle, and that both workplace and community issues are the concern of a committed trade union.

We firmly declare that the interests of all workers are alike, whether they be European, African, Coloured, Indian, English, Afrikaans or Jewish. We resolve that this coordinating body of trade unions shall strive to unite allworkers in its ranks, without discrimination and without prejudice. We resolve that this body shall determinedly seek to further and protect the interests of all workers, and that its guiding motto shall be the universalslogan of working class solidarity: 'An injury to one is an injury to all!'

Declaration of Principles adopted at the foundation conference of SACTU, 5 March 1955

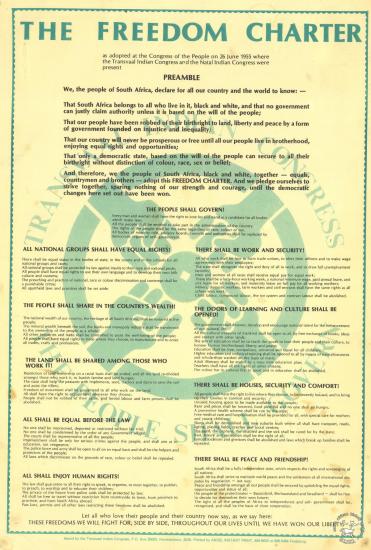

The NAC drafted the Freedom Charter from the demands for a nonracial South Africa collected from all over the country. It was adopted at the Congress of the People, held in Kliptown, outside Johannesburg, on 26 June 1955. The delegates included 2,222 Africans, 320 Indians, 230 coloureds and 112 whites: non-racialism in overt, self-conscious and affirmative form, projecting a vision of the future South Africa after the defeat of apartheid. Delegates and volunteers then reported back to their constituencies and began popularizing the Freedom Charter.

The rest of the 1950s saw countless campaigns: among the best remembered are demonstrations against the demolition of racially mixed freehold areas like Johannesburg's Sophiatown, boycotts of buses to protest fare increases, and of potatoes to highlight the conditions of farm labourers. The demands of the Freedom Charter for a non-racial South Africa provided a focus for unity in all these struggles, and the front was widened to include organizations not affiliated to the Congress Alliance.

Let us face it! The Nationalists have driven the African people to the point where many who were formerly not involved in political movements — who are today still outside the African National Congress — are up in arms against apartheid and for their rights. This is inevitable and must be welcomed. We believe that all vanguard fighters for freedom are led in the final analysis by the militant programme and actions of the ANC, but this does not mean that the ANC should expect or try to claim a monopoly of all anti-apartheid fight sof the people. Many actions may originate outside the ANC, some locally,some initiated by other leaders and groups. But if they are for the right policies, the ANC must welcome such actions and campaigns, and fight with them in the overall freedom fight.

The Women's Federationii represents a great working unity between the different women's organizations representing the different sections of South African women. To suggest that it is unnecessary or that the ANC Women's League 'could have done the job' is in the same breath to attack the very basis of the Congress movement itself. Why then do we not say to the Indian and Coloured Congresses and to COD, 'Why a National Action Committee? Why not come in with us?'

On the women's fighting front, the Women's Federation is the counterpart of the alliance built by the Congress movement. It is composed of the bodies that campaign together, that stand for the same programme, yet it is something mightier than all its independent parts, built by their cooperation on the basis of unity in action. Coloured, Indian and democratic European women, though not affected by passes today, have opposed these evils inflicted on African women because they know this is apartheid at work and no women's rights in future are safe under apartheid.

So the Women's Federation is part of the freedom front. It augments and strengthens it. It is a full-blooded member of the freedom movement and must not be regarded — or treated — as a step-child. Part of the Congress front,the Federation must nevertheless have freedom of action within it.

SECHABA: Bulletin of the Transvaal ANC, September 1956

The South African government had been closely monitoring the groundswell of support for the Freedom Charter. Police barred busloads of delegates from attending the Congress of the People, and Special Branch agents backed up by hundreds of armed police on horseback searched the crowd at Kliptown.

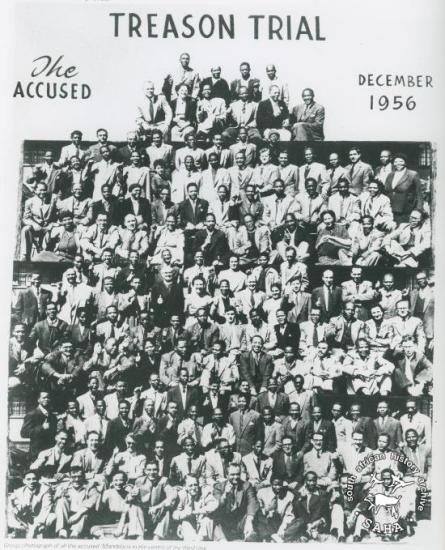

The state collected Congress documents in raids over the next year, and then in December 1956, some 156 people — two-thirds African and the rest Indian, coloured and white — were arrested and charged with High Treason. In a trial that lasted four years, the state tried to prove that the Freedom Charter was a communist document, part of a conspiracy aimed at instigating a violent overthrow of the state. The attempt failed: the trial ended with the acquittal of all defendants.

While the Congress movement suffered from this deactivation of its leadership, it also benefited from the lengthy and intensive contact between activists from all over the country afforded by the marathon trial. The wide spectrum of political views among the treason trialists has been summed up as 'ranging in outlook from Moses Kotane to Chief Luthuli'.v

In fact, since the defendants were seated in alphabetical order,the Communist Party leader and the Christian nationalist forged an intimate relationship, personally and politically, during the months they spent sitting next to each other in court. Similarly, blacks who had never experienced firsthand the non-racialism they had endorsed through the Freedom Charter interacted as equals with whites. Thus the developing unity, despite diversity, of the Congress movement owed a big debt to the Treason Trial.

NOTES

iIt was the call for the Congress of the People that prompted the South African Coloured People's Organization (SACPO) to formally change its name to the Coloured People's Congress (CPC).

iiPractice whereby coloured farmworkers were rewarded with periodic shots of wine or brandy throughout the working day, ostensibly to ensure productivity.

iiiThe Federation of South African Women (FedSAW), formed in April 1954, is best remembered for organizing an anti-pass demonstration on 9 August 1956, when 20,000 women from all over South Africa marched to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to present a petition to Prime Minister J. G. Strijdom.