Like the coloured community, Indians also gained a new level of political credibility through their overwhelming rejection of 'reformed' apartheid. Even before the tricameral parliament was mooted, the Indian community had begun mobilizing opposition to the 1981 elections for another government-controlled ethnic body, the South African Indian Council (SAIC). The Anti-SAIC Campaign had its roots in a critique of an organizing style that denies race-determined realities.

“The one major weakness that we had recognized in the past was that the Black Consciousness movement was based amongst the students, amongst certain sections of the youth and other educated or professional people, and that we had very little contact with the masses of our people as such. The fact that our organizations didn't actively involve our people, that was the one major criticism we had made of ourselves, and we needed to look at how to overcome that.

A second point is that there were two trends within the BC movement: there were those who believed that BC emerged out of nothing, that it stood on its own, that it was not part of historical developments, and rejected — even scorned — the traditional movements of our people and our history. Whereas the other trend said that we need to see ourselves as part of a struggle which has been going on for many centuries now, we need to see ourselves as part of what was happening in the 1950s, part of the Congress Alliance, all of those kinds of things.

We found that without that kind of historical analysis we would be unable to move forward, because we would be unable to communicate with our people. The people did not know us, they knew Nelson Mandela. In the community which I come from, the so-called Indian community, people did not know SASO, BPC, they knew the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC). If we were to organize effectively the masses of our people, we needed to understand their own culture of resistance, we needed to understand who the leaders were, what their background was."

MOHAMMED VALLI MOOSA, a former SASO executive member active in the Anti-SAIC Campaign.

Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the Congress of Indian South Africans, was a leader who was alert to the problems of the people and also an advocate of socialism. And the source of Natal Indian Congress philosophy is rooted in an era and in this man of achievements and ideals. You and I are the custodians of a great and noble tradition which we should nurture, enhance and defend against the dangers of dilution. For these dangers, from the little men in our midst who wish to betray this trust by participation in the President's Council and the South African Indian Council, are indeed serious today.

It requires little imagination to guess what Gandhi would have done if he were alive today and surveyed the sorrowful spectacle of our public life. His code of social freedom which rejects distinctions on the basis of birth, sex, caste, creed or colour would have, as it did during his stay in South Africa, made him lead the fight against apartheid. Gandhi believed in allowing people to decide for themselves. They are the final arbiters of independence and democracy. This is the single most important lesson we have to learn from Gandhi's experience: the absolute necessity for working with the people and articulating their demands. This is, therefore, the quintessential legacy of Gandhi for you and me.

Natal Indian Congress (NIC) vice-president Jeny Coovadia, speaking in Durban on the 112th anniversary of Gandhi's birth, 11 October 1981

Appeals to the Gandhian tradition had more resonance for the older generation than for the youth.i The politicization of many Indian students stemmed from the more immediate experience of the nationwide school boycotts of 1980.

Student leaders from all over the country actually converged in four big cells, and in fact, all those people who went into that particular experience came out ten times stronger. I think we [Indians from Natal] learned some fairly serious things in the couple of months that we were in detention. We learned that unless the African people are liberated in South Africa, there can be no liberation for any other community And that although we went in idealistically, believed in non-racialism and all that, we hadn't, up to that point, understood it: that non-racialism actually means the liberation of the African people in the first instance. What we learned from those experiences was basically that one needs a national democratic approach, where any single person interested in challenging apartheid is welcome into that broad struggle.

You have that kind of ethnic division between Indians, Africans, coloureds and whites, with Indians having it, not the worst in terms of oppression, but the worst an terms of the minority syndrome. They are the smallest percentage of people. They always fear that, 'We can't challenge the white government because they'll trample all over us, we can't actually challenge the Africans because they are far superior in numbers, and they will wipe us out and send us to the Indian Ocean,' as the saying goes. And then there is a lot of fear attaching to that, together with apartheid propaganda, which consistently attempted to keep the Indian community as the sort of jam between two slices of bread.”

ALF KARRIM, chairperson of the committee coordinating the boycott in Natal, who was detained in Modder Bee Prison in the Transvaal

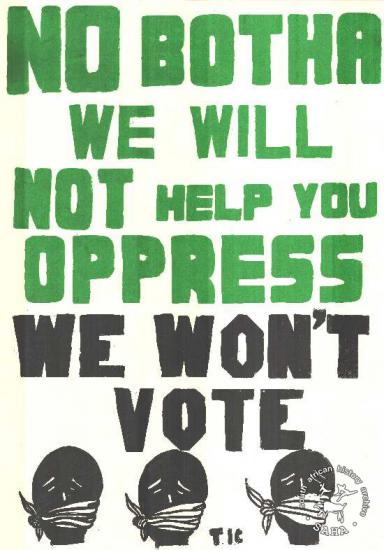

The boycott campaigns against elections to the SAIC and the tricameral parliament were led by the Indian Congresses of Natal and the Transvaal, the two provinces with the greatest concentration of Indians. The NIC had been revived back in 1971, when it weathered attacks from Black Consciousness supporters chanting, 'Think Black, not Indian'. The revival of the TIC in 1983 sparked a hot debate within anti-apartheid circles over the issue of ethnically-based organization.

The re-formation of the old Transvaal Indian Congress has created something of a stir. One of the oldest political organizations in South Africa, the TIC was an integral part of the ANC-led Congress Alliance. Now the reconstitution of the TIC has again raised questions about a racially specific organization adopting a non-racial position. AZAPO publicity secretary Ishmael Mkhabela has stated that the formation of TIC will strengthen the forces of ethnicity. 'From our point of view, any ethnically based organization by Indians, coloureds or Zulus is directly in line with Pretoria's policy of apartheid,' said Mkhabela. Others disagree with AZAPO. General and Allied Workers Union (GAWU) president Samson Ndou sees the TIC as a people's, not an ethnic organization. Transvaal Anti-SAIC chairperson Essop Jassat points out that South African laws have forced different people to live in separate ghettos.It is easier for them to organize and mobilize politically from their respective areas,' says Jassat. And GAWU's Sydney Mafumadi suggests that, `How the TIC is structured is not fundamental: the fundamental issue is that its aims and objectives are non-racial.' AZAPO's categorization of the TIC as 'ethnic' needs to be assessed in the light of three factors: the TIC's adherence to non-racialism, whether it manipulates ethnicity and racial symbols in its activities, and the interests which it represents. The Congress Alliance comprised racially- or nationally-specific organizations, linked through organizational structures and joint campaigns. Non-racialism involves a statement about a future society in which racism will be eradicated; it also implies that race is not the most important social category in society. This suggests that the class structure of South Africa is a more fundamental force than racial factors.

Ethnic organizations mobilize on the basis of a set of perceived ethnic interests and symbols. This, for example, is a component of Inkatha's Zulu nationalism.ii But there is no indication that the TIC, or any of the other racially-specific Congress organizations, operated on that basis. Finally, there is the question of the interests which an organization represents. This involves the relative weight that working class, petty bourgeois, peasant or other interests enjoy within an organization or alliance. An attempt to establish the primacy of working class or popular interests is unlikely to merit the ethnic tag. These are some of the issues which need to be raised in assessing AZAPO's attack on the TIC.

Editorial, WORK IN PROGRESS, February 1983

“Occasionally when you do field work and you go to people's houses, they ask you, 'What guarantee do we Indians have that when the blacks take over we won't get booted out?' Then when you're talking to them, you can't talk as a black person — you have to then sort of connect with people at the level at which they are thinking. When relating to ordinary working class people, you have to talk in terms of Indian and coloured. That is why it's necessary to have an Indian Congress: because that's how people perceive themselves.The sophistication of the ideological state apparatus,iii the fact that people live in separate areas, the fact that in your documents, in any application, when there's 'race' you have to write 'Indian', the school that you go to is Indian — it just has such an impact on people's way of thinking. It would almost be inhuman for people not to have that initial kind of Indian, African, coloured or white consciousness.

They've got a special radio programme for Indian people, something called Radio Lotus. It's such an important thing, in terms of this whole move by the state of using Indian people to develop this kind of Indian consciousness. Because it has a certain kind of appeal, through the songs and stuff like that — especially older people would listen to the radio station. All those things, collectively, have a tremendous impact in shaping the way people think of themselves and the way they think of others as well.

I look forward to the day when there won't be a need for an NIC, and I hope that it's around the corner. I think it would be a good thing for the cause of non-racialism when eventually we are in a position to do away with the Indian tag, but I think in this period, so long as the majority of the people still see themselves as being Indian, it is necessary to retain the label.” iv

KUMI NAIDOO, NIC member and an SRC leader at the University of Durban-Westville

There is one exceptional circumstance in which the apartheid system groups Indians together with Africans and coloureds: in jail. For many, the prison experience marks the first time they have ever lived in close contact with people of other races. Yet even political prisoners feel the tensions arising from divergent ethnic identities, with the smallest minority group finding it most trying — though often also most rewarding.

“First I was kept in Port Elizabeth prison. That was a really weird experience, because there were murderers and robbers and what-have-you, and they really looked up to me as a political prisoner. In Port Elizabeth — everywhere out of Durban — Indians are well-off, by and large, because the professionals moved out of Durban. And so that's their experience of Indians: professionals, doctors, lawyers, businessmen. Here was an Indian who was fighting for black people, and it was quite something, you know. You just felt these positive vibrations, and you said, 'This is worthwhile, it's a contribution to non-racialism.'Prison was the first time I'd actually lived with African people in very, very close daily contact, and I was very conscious of being an Indian, of being different. And wanting to be accepted — ja, I was very conscious of that. The other political prisoners were very accommodating. Of course, the problem that crept in was the language — especially when a lot of youngsters came in from Port Elizabeth who couldn't speak English very well. The others were forced to speak Xhosa most of the time to them, and I would feel a bit alienated. Later on other political prisoners came, who weren't so sensitive to my being Indian. I remember when we were discussing a hunger strike and them deciding a course of action, and I asked, 'What have you decided?' and they interpreted my questioning as not wanting to be part of the action. So all those tensions were there.

I was very conscious of it, though at the time I tried not to admit it. Because you wanted to feel that you were a black person and you were part of the struggle. But right throughout I was conscious of being Indian, and trying to prove myself.”

DEVAN PILLAY, a university student who served a year in prison for ANC activities in 1981

It was this palpable reality of ethnic identification that sustained the argument favouring constituency-based politics. Judgment of the Indian Congresses was ultimately based more on their achievements — most notably, the overwhelming boycott of the tricameral elections — than on the structures used to realize these results. Debate continued, however, on how best to bridge the gap between the theory of transcending ethnicity and the on-the-ground experience.

“When I look at how people organize today I'm very concerned. Although people don't directly say that they are organizing on a racial basis, the reality is that they are. I understand the value of that kind of strategy, but at the same time you're actually pandering to a very backward mentality by assuming that a coloured person won't relate to, say, an Indian person in Lenasia, or that a comrade from Soweto couldn't come and organize in a coloured area or vice versa. I've often heard activists say, 'If we have African comrades coming to Riverlea, maybe they'll have problems.' My feeling about that is perhaps they will have problems, but isn't that what we're fighting for?I remember quite well during the anti-election campaign, going door to door people would say, 'How come you people are talking about black majority rule but there are no African people here with you?' There's a need for people to see this non-racialism that we talk about in practice. You can't say, okay, for now we're going to work like this as ethnic groupings, and then in the next five years we're going to double our efforts so that people will accept one another as different races.

The Federation of Transvaal Women, for instance, organizes on a non-racial basis. We have women's groups in communities all over the Transvaal, and some of those groups are mixed groups — it depends on who comes together in a certain geographical area. In my particular area, the women that have come together are only coloured women, and for me, that's problematic. And yet on a pragmatic level, I can understand that we have to organize those women into projects within their areas.

I believe we're going to have a hell of a problem after liberation. Because it doesn't mean that we are suddenly going to have non-racial living areas, you know. I think for a long time after liberation there will still be Soweto and there'll still be Newclare, and there will still be Riverlea and Bosmont and Fordsburg,v and the people who live there now will live there then. This is something which one raises in the UDF, and I think that many people share the concerns I have, but have the same problem as I do as to exactly how do we get to the point where our strategies can also include non-racial campaigns that everyone can become involved in. We mustn't just speak about non-racialism — we must work in a non-racial way.”

JESSIE DUARTE, organizer for the Federation of Transvaal Women (FedTraw) from Johannesburg's coloured township of Riverlea

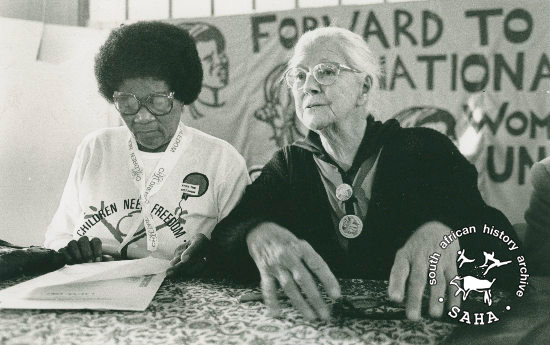

The perennial debate over the nature of white involvement in mass-based organization also resurfaced, this time without the racial overtones of the Black Consciousness era, but linked instead to an attack on the class base of organizations that included whites and liberals.

“In 1983 CAYCO was formed, and I remember there was this message of support from NUSAS. A lot of people felt that there was no ways that whites could be involved in the struggle, and there was no way that they would allow white people into CAYCO — which caused lots of big differences. I lost lots of good friends during that argument, who felt that white students who were involved in political organizations were sons and daughters of the ruling class, and we can't trust them all the way in the struggle.I knew that there were a lot of white people who were just as committed as I was. I was sure that a lot of coloured or African people who were involved in student politics, once they got their degrees, there were chances that they'd also become managers or doctors or lawyers and forget about the struggle.

Strangely enough, most of the people who were anti-white in the debate were from middle-class areas. For myself, coming from a middle-class family, I could understand and sympathize with that kind of argument that they [whites] weren't going to go all the way, but my feeling was that it's a broad struggle and we need to fight apartheid on all fronts, and therefore we should include all those who purport to be part of the mass movement and are willing to work, and whether they dropped out along the way had nothing to do with whether we were going to work with them now.

That was the basis of the argument — but then we were out-voted and NUSAS wasn't allowed observer status in CAYCO. It was a very dirty fight. In our branch of CAYCO in Lansdowne [middle-class coloured area] we had the person who led the argument that we shouldn't have NUSAS involved in any way. She tried to present it as a class thing, that you don't want the bourgeoisie to lead the struggle, that if the working class aren't leading the struggle we're going to be deflected from our socialist path. Then this very person, two weeks after this whole debate, went to NUSAS and expected them to print pamphlets for her.”

“How did NUSAS respond?

They said that they weren't prepared to be used any longer, that people should accept that they were just as committed as anyone else was — which they were.

Do you support the tactic of 'ethnic' organizing, in which the different race groups work in their own group areas?

Let me put it this way. Since the launch of the UDF in 1983, we needed everyone who could work to give all their free time to organizing. We had students from NUSAS, we had the white members of the United Women's Organization coming with us into areas like Mitchell's Plain, into Gugulethu, into Langa. And this was the first time that something like that had ever happened in Cape Town, that you had white people going into black areas to politicize people. And that hasn't stopped since then. With the Million Signatures Campaign of the UDF vi we had white comrades who went with us, who went into areas that I'm too scared to go into, where gangsterism is rife and where young ladies don't walk around late at night, and since then it's never been a problem or a question of: you're a white person and therefore must only organize in your own area. So that whole non-racial way of organizing has been ingrained since the launch of the UDF.

It's the whole question of attacking and destroying apartheid on all fronts.We're fighting for a non-racial South Africa — we don't want the problem of having to build non-racialism after the revolution or after negotiations or after whatever's going to happen. And it's important for us to show people that our organizations are non-racial, to show that we aren't going to do to white people what they do to us, that we're just as prepared to work with them now as we will be in a new society.

Are you critical of groups like the Transvaal or Natal Indian Congresses that organize mainly in their own communities?

No, I'm not. For me, it's the same principle that I'm a member of a women's organization. Why do we have women's organizations and we don't have men's organizations? There are certain sectors of the community that need to be organized as a sector, in order to ensure that when freedom comes we'll be able to have as many people supportive of us as possible.”

REHANA ROSSOUW, Cape Youth Congress (CAYCO) viiactivist

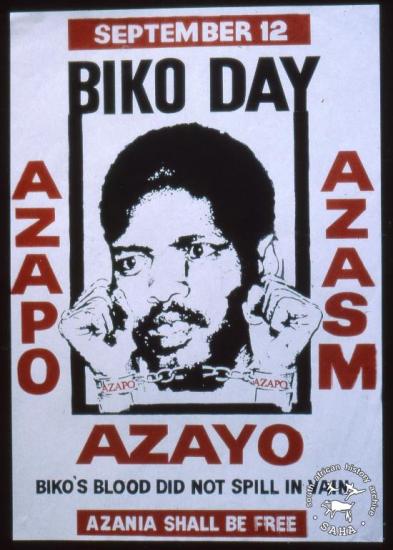

The strongest criticism of mobilization on ethnic lines came from a new alignment of political groups that jelled shortly before the UDF was launched. A wide range of organizations and political tendencies came together in the National Forum Committee (NFC), from the BC-oriented AZAPO to the fringe-left Cape Action League.viii What united them was a rejection of the 'national democratic struggle' endorsed by the UDF and the ANC, which aimed to build the broadest front of opposition to apartheid, led by workers but supported by all sections of the oppressed, as well as progressive members of the white minority. The NFC stood for the eradication of 'racial capitalism' and its replacement by an 'anti-racist' socialism. This transformation was to be brought about by the black working class; the NFC rejected any 'unprincipled' alliances that might dilute the revolutionary content of the struggle.

Our struggle for national liberation is directed against the system of racial capitalism which holds the people of Azania in bondage for the benefit of the small minority, of white capitalists and their allies, the white workers and the reactionary sections of the middle classes. The struggle against apartheid is no more than a point of departure for our liberatory efforts. Apartheid will be eradicated with the system of racial capitalism. The black working class, inspired by revolutionary consciousness, is the driving force of our struggle. They alone can end the system as it stands today because they alone have nothing at all to lose. They have a world to gain in a democratic, anti-racist and socialist Azania. It is the historic task of the black working class and its organizations to mobilize the urban and rural poor, together with the radical sections of the middle classes, in order to put an end to the system of oppression and exploitation by the white ruling class. Successful conduct of the national liberation struggle depends on the firm basis of principle whereby we will ensure that the liberation struggle will not be turned against our people by treacherous and opportunistic 'leaders'. Of these principles, the most important are:I. Anti-racism and anti-imperialism;

II. Anti-collaboration with the oppressor and its political instruments;

III. Independent working class organization.

MANIFESTO OF THE AZANIAN PEOPLE; adopted at the National Forum Committee launch, Hammanskraal, 12 June 1983

Adherents to the Azanian Manifesto represented a small minority, with a perspective that tended to alienate potential allies. UDF activists argued that the struggle for non-racial democracy required the widest possible anti-apartheid base — in which workers and their allies are strong enough to support the building of socialism. Furthermore, the UDF suspected that behind the NFC's slogans and semantics lay an intellectual elite's fear of the cut and thrust of mass-based politics.The word `non-racial' can be accepted by a racially oppressed people if it means that we reject the concept of race, that we deny the existence of races and thus oppose all actions, practices, beliefs and policies based on the concept of race. If in practice — and in theory — we continue to use the word non-racial as though we believe that South Africa is inhabited by four so-called races, we are still trapped in multi-racialism, and thus in racialism. Non-racialism, meaning the denial of the existence of races, leads on to 'antiracism', which goes beyond it, because the term not only involves the denial of race, but also opposition to the capitalist structures for the perpetuation of which the ideology and theory of race exist. We need, therefore, at all times to find out whether our non-racialists are multi-racialists or anti-racialists. Only the latter variety can belong in the national liberation movement.

The fact remains that 'ethnic' or 'national group'ix approaches are the thin end of the wedge for separatist movements and civil wars fanned by great-power interests and suppliers of arms to opportunist 'ethnic leaders'.Does not Inkatha in some ways represent a warning to all of us? Who decides what are the 'positive features' of a national group?

Only the black working class can take the task of completing the democratization of the country on its shoulders. It alone can unite all the oppressed and exploited classes. It has become the leading class in the building of the nation. It has to redefine the nation and abolish the reactionary definitions of the bourgeoisie and of the reactionary petty bourgeoisie. A non-racial capitalism is impossible in South Africa. The class struggle against capitalist exploitation and the national struggle against racial oppression become one struggle under the general command of the black working class and its organizations. Class, colour and nation converge in the national liberation movement. Cultural organizations that are not locally or geographically limited for valid community reasons should be open to all oppressed and exploited people. In this way the cultural achievements of the people will be woven together into one Azanian fabric.

In this way we shall eliminate divisive ethnic consciousness and separatist lines of division without eliminating our cultural achievements and cultural variety. In this struggle, the idea of a single nation is vital because it represents the real interest of the working class and therefore of the future socialist Azania. 'Ethnic', national group or racial group ideas of nationhood in the final analysis strengthen the position of the middle-class or even the capitalist oppressors themselves. I believe that if we view the question of the nation and ethnicity in this framework, we will understand how vital it is that our slogans are heard throughout the length and breadth of our country. One People, One Azania! One Azania, One Nation!

"Nation and Ethnicity in South Africa"; address by Cape Action League executive member and NFC founder member Neville Alexander, delivered at the NFC launch

By the mid-1980s, there was no doubt that the concept of non-racialism held far more sway than 'anti-racism'. The NFC's racial capitalism had been eclipsed by the broad front politics now enthusiastically embraced by UDF supporters.x This period also saw a revival of the theory of `colonialism of a special type’,xi which compared the conflicting forces in South Africa to a colonial ruling bloc and a colonized majority contained within the same territory, with both camps comprising all races and classes. In many ways, these theoretical debates echoed those between the ANC and the Africanists of 25 years before, for the NFC accommodated individuals and organizations whose rhetoric recalled that of the PAC.

“Only after we have got our land back can we then talk of reconciliation, can we then talk of a non-racial society, can we talk of complete democracy. But before the contradictions are resolved, we are just dreaming that we are free already, and we aren't. It is the Africans themselves who have to take political decisions about the struggle — any white who comes in can come in only to assist. What we've had up to this point is we've had whites who are sympathetic to the struggle, who come essentially to try and give advice. They, in fact, take over the struggle. I've never ever met a white who will just accept a place and say, `Okay, I'm just a member.' I believe that we need to work out our own solutions ourselves, and in the process of struggling, we will be able to get the confidence we need.When you said 'We Africans have to do it ourselves; did you mean to exclude coloureds and Indians?

I have found that very many coloureds don't accept themselves as African — but there are coloureds who accept themselves as African. There are some Indians who do not identify with the Africans, but there are some who have thrown in their lot entirely with the indigenous Africans. But to be very frank, very few of them do realize that they are, in fact, in exactly the same position as the indigenous Africans.

And what about African people who ally themselves with the state - the homeland leaders, the informers, the police?

By the way, we shouldn't look at this as a racial sort of division. It's essentially those who are oppressing as against those who are oppressed, so that the Africans, the coloureds, the Indians who choose to align themselves with the oppressor have no place in this struggle.

Would you accept that there are whites who align themselves with the oppressed?

The problem we have found with the whites who align themselves with the Africans is that they are beneficiaries of this whole system of oppression. When they come in and say we want to be on your side, they try to improve our conditions rather than to break down the entire structure. There might be one or two who are committed to a complete breakdown of the structure, but when you organize a political party, you don't organize in terms of the exceptions to the rule. Ultimately, we have to carry the burden of the oppression and we are the people who have to break it.

`We' means . . .?

The indigenous Africans, and those coloureds and Indians who call themselves Africans.

But couldn't you also say that there are Indians and coloureds who are beneficiaries of the system of oppression just as whites are?

I think the essential difference is that the Indian's historical experiences are the same as that of the indigenous African: he was robbed of his land, carried by force and brought here. So that even in South Africa he enjoys second-class citizenship. The Indian might get a little more pay at work, he might be a little more educated, but he has been through exactly the same experiences as the indigenous African, so that at the emotional level it is much easier for him to identify with the African. That is why it's much easier for us to accept him as an African.

Do you recall engaging in arguments and discussions about non-racialism back in the 1950s and 1960s?

Our major problem then, as it still is today, was that people try to project the PAC and the BC as being anti-white, and that is not true. So you had to try and explain the difference between being anti-white and between wanting Africans to take their own political decisions. We would, in fact, be accused of being racist, but our documents stated very clearly that we believe in only one race, the human race. We believe that once we liberate Azania, we'll have a non-racial society, because we don't believe in any specific race.”

JOE THLOLOE, jailed for PAC activities in 1960, but released on paying a fine, arrested again in 1982 but acquitted on appeal, and a founder member of the BC-oriented Union of Black Journalists and its successor, the NFC-supporting Media Workers of South Africa (MWASA)

The parallels between the historic ANC-PAC debate over non-racialism and the current controversy were not lost on the South African government. The widespread dissemination of anti-UDF pamphlets, purporting to be issued by the NFC but clearly aimed at provoking divisions, immediately raised suspicions that they were smear pamphlets produced by a Security Police 'dirty tricks' unit.

National Forum Committee rejects the so-called `United Democratic Front' for the following reasons:1.Any black person genuinely committed to liberation from white oppression will reject participation by members of the white oppressor class in the liberation struggle.

2.The UDF is the old white-dominated South African Communist Party/ANC alliance dressed up in a new disguise. Admission of 'sympathetic' white organizations such as NUSAS and the 'Black Sash' is merely the pretext for continued white minority control under a different ideology.

3.The UDF is an obstacle in the path of the total liberation of Azania by blacks for blacks.

Pamphlet distributed in Johannesburg in late 1983

The debate over `ethnic' mobilization for non-racial ends was reopened five years after the 1983 TIC controversy, this time with regard to the NIC. Critics charged that it was being manipulated by a 'cabal' that was exercising undue influence over Natal political affairs. Underneath the accusation lay the African majority's recurrent fear of potential domination by a more privileged minority. In Natal, these fears were compounded by the fact that Africans were actually outnumbered by Indians in the major city of Durban.xii Mistrust between Africans and Indians had been further exacerbated by the 1985 Inanda violence, an upheaval which tore apart an African-Indian community that had been invoked as a model of non-racial co-existence for the past century.xiii

Issued by: National Forum Committee, AZAPO, SACOS

Criticisms of the MC often confuse arguments about ethnicity with the failure of the MC to develop a sufficiently strong mass base (particularly among workers), the class basis of its leadership, the lack of a deeply-rooted enough democratic practice, and a certain monopoly of resources and skills. Although some of these problems are to an extent related to the constituency the NIC organizes, they do not automatically flow from the fact that the NIC organizes the Indian community. It is possible to address these difficulties without the NIC having to abandon its organization of the Indian community.Many of these difficulties are not peculiar to the NIC. In different forms, most political organizations, in this country and elsewhere, have had to deal with similar problems. To the extent that the MC deepens its democratic practice, the question of monopoly of skills and resources can be addressed. This is mainly a problem at the subjective level. But it also reflects the objective situation: NIC activists often have more formal education, more developed skills in certain respects, and greater freedom to operate politically, compared to people in the townships. The more democratic structures are entrenched in the townships, the easier it will become to attend to these problems.

The issues surrounding skills and resources apply to many organizations in this country and elsewhere in the world. In the South African context they take a racial form and are therefore more sensitive. But they must be addressed in their wider general context as well. Many of the questions raised about the NIC reflect the complexity of the South African struggle, and point to the difficulties in creating true non-racialism and democracy. They have lessons to offer the entire democratic movement. And the challenges they pose will ultimately have to be addressed by the democratic movement as a whole.

YUNUS CARRIM, NIC executive member xiv

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 20 AS A PDF

NOTES

i Many Indian activists identified more closely with radical Indian leaders like Yusuf Dadoo, the former Indian Congress leader who became SACP chairman after leaving the country. His death in 1983 was commemorated with a publication that was so enthusiastically received by the Transvaal Indian community that it was said that the Security Police had tried to ban it and, failing that, had restricted access to 'one copy per family' (Congress Resister: Newsletter of the Transvaal Indian Congres.s, September 1983).

ii The movement led by KwaZulu's Chief Gatsha Buthelezi, who initially won popular support for refusing to accept 'independence' for the homeland, but is now widely criticized for building a personal and regional power base rooted in Zulu chauvinism, in (often violent) opposition to mass-based movements like the UDF and ANC.

iii This articulation of the concept of the material basis of ideology, as contained in institutions such as family and school, is drawn from the French philosopher Louis Althusser (see Chapter 15, note 8).

iv The unbanning of the ANC, SACP and other organizations in February 1990 sparked a debate over whether 'ethnic' organizations like the TIC, NIC and JODAC (see Chapter 21) should disband and dissolve into the ranks of their ally, the ANC. A discussion paper for a Johannesburg activist forum, 17 March 1990, The Road Ahead', argued: 'What we must avoid at all costs is sidestepping the problems that led us to establish organizations catering for the distinct character of specific communities. We must organize in such a way that these people trust us and feel that their security is best achieved through the ANC.'

vColoured and Indian areas of Johannesburg.

viA petition against the new constitution in 1983-84.

viiA UDF-aligned coordinating body for youth in the Western Cape.

viii Launched in 1982 as the Disorderly Bills Action Commitee (DBAC), a loose association of Western Cape organizations opposed to the President's Council and the so-called Koornhof Bills. By 1983, the larger groupings that went on to form the Western Cape UDF (e.g., CAHAC) had dropped out of DBAC, and it was renamed CAL. Various incarnations of the Unity Movement represented the dominant political tendency in CAL

ix This term is taken from the Freedom Charter (second clause): 'All National Groups Shall Have Equal Rights'.

x The concept of racial capitalism was prevalent in South African left political circles in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but the fact that anti-UDF and anti-ANC forces embraced (their version of) racial capitalism as a means of negating the theory of national democratic struggle contributed to a discrediting of the term and a decline in its currency.

xi Initially articulated by and associated with the SACP.

xii Durban's racial balance began shifting during the 1970s, the result of a tremendous influx of Africans caused by factors ranging from deteriorating rural conditions to Inkatha-related violence. Quantifying the African-Indian ratio of the Durban population is complicated, however, by the fact that a number of African areas traditionally considered part of Durban have been incorporated into the KwaZulu homeland.

xiii Studies of this unrest have debunked the facile comparison with the 1949 African-Indian violence, highlighting the historical framework and political context of the 1985 conflict, and specifically exploring the role of Inkatha vigilantes in attacking UDF supporters. See Heather Hughes, 'Violence in Inanda, August 1985' , Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3, April 1987 and the numerous studies she cites.

xiv Excerpted from "The Natal Indian Congress: Deciding on a New Thrust Forward', Work in Progress, No. 52, 1988.