The incipient non-racialism of the working-class socialist movement was rivalled by a joint venture of white liberals and black elites. European missionaries who came to South Africa in the late eighteenth century built a base for a liberal alternative to crude white domination of black. The assimilation of a faithful black middle class was seen as the best means of ensuring the stability of the society defined by race.

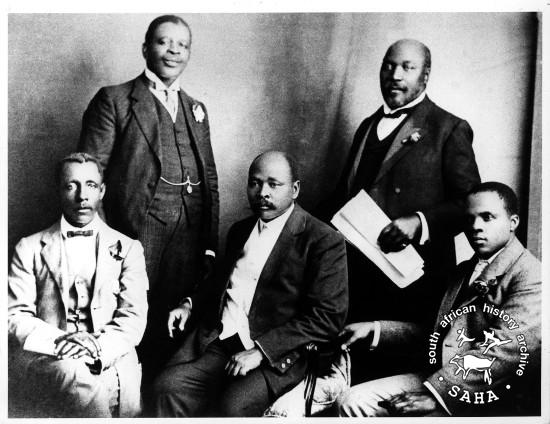

A group of mission-educated black professionals and traditional chiefs founded the South African Native National Congress in 1912 `to so avoid the exploitation of Native fears and grievances by irresponsible agitators'.i The SANNC's liberal allies were heartened by its focus on racial discrimination as an affront to the dignity and aspirations of the elite, and by its keen hostility to a class analysis of black oppression.

I beg to explain the cause of my delay in answering your letter. I had to attend the Native Congress in Bloemfontein to prevent the spread among our people of the Johannesburg Socialist propaganda. I think you are aware of our difficulties in that connection. The ten Transvaal delegates came to Congress with a concord and determination that was perfectly astounding, and foreign to our customary native demeanour at conferences. They spoke almost in unison, in short sentences, nearly every one of which ended with the word 'strike'.

It was only late on the second day that we succeeded in satisfying the delegates to report, on getting to their homes, that the Socialists' method of pitting up black and white will land our people in serious disaster, while the worst that could happen to the whitemen would be but a temporary inconvenience.

When they took the train for Johannesburg at Bloemfontein station, I am told that one of them remarked that they would have 'converted Congress had not De Beers given Plaatje a Hall'. This seems intensely reassuring as indicating that Kimberley will be about the last place that these black Bolsheviks of Johannesburg will pay attention to, thus leaving us free to combat their activities in other parts of the Union. Only those who saw the tension at this Congress can realize that this discussion hall of ours came at just the right time for South Africa.

Letter from SOL PLAATJE, first SANNC secretary-general, writing to De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd in Kimberley about the company's donation of an old shed for use as an 'Assembly Hall for Natives; 3 August 1918 ii

The alliance of white philanthropists and black nationalists paralleled that of white workers and the ruling class, in that the black partners were also accomplices in the continuing exploitation of the majority. The elites were concerned about securing a niche within the colonial system, not about changing the system itself.

No restructuring of the economy was envisaged, nor was there even a challenge to racial differentiation, for this approach was not non-racial but 'multi-racial'. White and black reformists recognized the value of ‘constructive segregation'.iii This philosophy in the 1920s and 1930s, combined with the renunciation of militant trade union and Communist Party activists, coincided with an all-time low in the popular support of the African National Congress, as the SANNC was renamed in 1923.iv

An important international influence on this evolving multi-racialism came from the United States. Philanthropic initiatives like the Phelps- Stokes Fund promoted African education and training along the lines of a model developed in the American South. South African intellectuals — whites and some blacks — were encouraged to travel to the US to witness the multi-racial society firsthand.

A one-time apologist for segregation, academic Edgar Brookes returned from his Phelps-Stokes-sponsored trip to America a zealous convert to the cause of incorporating a black middle class into the white-dominated system. In 1929, with the additional aid of another New York-based funding agency, Carnegie, Brookes founded the South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR). According to the `race relations' concept South Africa was not a unitary society, but rather one of distinct races with inherently different interests stemming from their diverse cultures. Resolution of conflict between the races thus demanded a reconciliation of the immutable elements of this multi-racial societyv

Bantuvi nationalism must reach out towards Bolshevism. How could it be otherwise? If there is a clearly defined proletariat anywhere in the world, it is in South Africa. Happier or wiser countries postpone or altogether avoid a Marxian `class war' by the creation of common interests, by opening doors of opportunity enabling the ambitious member of the proletariat to escape into the governing class, at the very least by ostentatious professions of a single national unity transcending class distinctions.

In South Africa we follow a different course. We try to prevent the multiplication of common interests, we close almost every door of opportunity, and we loudly proclaim the impossibility of union in a single nation. Class becomes associated with something definite and tangible such as colour.

The stage is inevitably set for the 'class war'. As a member of the bourgeoisie myself, I hope it is not set for the `dictatorship of the proletariat'. As a liberal, I believe that only swift and far-reaching reforms and many more opportunities for self-realization on the part of the Bantu can create the impossibility of such a dictatorship. I insist that those who are fighting the Battle of the Bantu are the real friends of the white man and the whole South African community.

EDGAR BROOKES, delivering the Phelps-Stokes lecture at the University of Cape Town, 1933vii

Multi-racialism must be seen in its historical context. While Brookes eventually joined the Liberal Party, others branched off the multi-racial path, ultimately arriving at an endorsement of the non-racialism of the popular movements. One such case was that of Bram Fischer, the distinguished Afrikaner advocate, grandson of the Prime Minister of the Orange Free State, and son of the judge-president of the province's Supreme Court, who died serving a life sentence for attempting to overthrow the South African government.

Though nearly forty years have passed, I can remember vividly the experience which brought home to me exactly what this `white' attitude is, and also how artificial and unreal it is. Like many young Afrikaners, I grew up on a farm. Between the ages of eight and twelve, my daily companions were two young Africans of my own age. I can still remember their names.

We roamed the farm together, we hunted and played together, we modelled clay oxen and swam. And never can I remember that the colour of our skins affected our fun or our quarrels or our close friendship in any way.

Then my family moved to town and I moved back to the normal white South African mode of life, where the only relationship with Africans was that of master to servant. I finished my schooling and went to university.

There one of my first interests became a study of the theory of segregation, then beginning to blossom. This seemed to me to provide the solution to South Africa's problems and I became an earnest believer in it.

A year later, to help in a small way to put this theory into practice — because I do not believe that theory and practice can or should be separated — I joined the Bloemfontein Joint Council of Europeans and Africans viii a body devoted largely to trying to induce various authorities to provide proper, and separate, amenities for Africans. I found myself being introduced to leading members of the African community. I found I had to shake hands with them. This, I found, required an enormous effort of will on my part. Could I really, as a white adult, touch the hand of a black man in friendship?

That night I spent many hours in thought, trying to account for my strange revulsion when I remembered I had never had any such feelings towards my boyhood friends. What became abundantly clear was that it was I and not the black man who had changed, that despite my growing interest in him, I had developed an antagonism for which I could find no rational basis whatsoever.

One night, when I was driving an old ANC leader to his house far out to the west of Johannesburg, I propounded to him the well-worn theory that if you separate races you diminish the points at which friction between them may occur and hence ensure good relations. His answer was the essence of simplicity. If you place the races of one country in two camps, said he, and cut off contact between them, those in each camp begin to forget that those in the other are ordinary human beings, that each lives and laughs in the same way, that each experiences joy or sorrow, pride or humiliation for the same reasons. Thereby each becomes suspicious of the other and each eventually fears the other, which is the basis of all racialism.

I believe no one could more effectively sum up the South African position today. Only contact between the races can eliminate suspicion and fear; only contact and cooperation can breed tolerance and understanding.

Segregation or apartheid, however genuinely believed in, can produce only those things it is supposed to avoid: interracial tension and estrangement, intolerance and race hatreds.

BRAM FISCHER, speaking about his political experiences in the 1920s, in a speech from the dock during his trial for sabotage and membership of the underground South African Communist Party (SACP), 28 March 1966

Bram Fischer was an exceptional person and his response to his Joint Council experience was also exceptional. Most whites were little moved by interracial contact, and most blacks saw the Joint Council movement as at best ambiguous, and at worst, a scheme to co-opt and depoliticize African nationalists. As a result, the Joint Councils never gained political support beyond a small section of the black middle class, and were rejected even by the conservatives who then led the ANC.

Perhaps the most significant effect of this period of collaboration between white and black elites came in the form of a building black backlash against what African nationalists perceived as white control. By the late 1930s, the ANC's leadership was under pressure to adopt a more militant political stance.

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 3 AS A PDF

NOTES

i Principal SANNC founding member Pixley ka I. Seme, in describing the purpose of the body. Note also that a female counterpart to the SANNC was formed in 1913: the Bantu Women's League, which grew out of the 1913 women's anti-pass campaign in the Orange Free State (OFS). Led by the OFS Native and Coloured Women's Association, the protest included both African and coloured women, and thus marked the first non-racial unity in struggle among South African women.

ii Cited in Brian Willan, Sol Plaatje• South African Nationalist 1876— 1932, Heinemann Educational Books and Ravan Press, 1984, a work that succeeds in illuminating Plaatje's literary and political contributions, as well as the role he (and other early nationalist leaders) played in buffering the ruling class from more militant challenges.

iii Jan Hofmeyr, a liberal cabinet minister in the Smuts government, in 1930, rejecting the two 'extreme' policies of repression and equality; quoted in William Minter, King Solomon's Mines Revisited• Western Interests and the Burdened History of Southern Africa, Basic Books, 1986.

iv For further exploration of this theme, see Paul B. Rich, White Power and the Liberal Conscience• Racial Segregation and South African Liberalism, Ravan, 1984.

v Other factors were also relevant, e.g., the rise — albeit short-lived — of the ICU, the CPSA's own serious decline in membership, and the ousting of ANC President Josiah Gumede after his visit to the Soviet Union.

vi Quoted in Robert Davies, Capital, State and White Labour in South Africa: 1900— 1960: An Historical Materialist Analysis of Class Formation and Class Relations, Harvester Press, 1979.

vii An Nguni word, meaning 'people', the term describes southern African ethnic groups, but was co-opted by the apartheid regime to refer to Africans, e.g., Bantu Education.

viii The Joint Council movement, with councils in the major South African cities, was launched in 1921, following the African miners' strike and a tour of South Africa by Phelps-Stokes Fund Director Thomas Jesse Jones and its African member, Dr J. E. K. Aggrey of the Gold Coast (now Ghana), who proselytized about`interracial cooperation' and the model of American 'negro' industrial training offered by Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute.