"General, your tank is a powerful vehicle

it smashes down forests and crushes a

hundred men.

But it has one defect:

it needs a driver.

General, your bomber is powerful.

It flies faster than a storm and carries

more than an elephant.

But it has one defect:

it needs a mechanic.

General, man is very useful.

He can fly and he can kill.

But he has one defect:

he can think." 1

Reviving the ECC

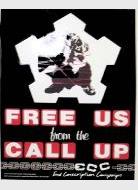

The ECC had served as the central bonding agent for the war resistance movement. Once it was banned under restriction orders in August 1988 during the State of Emergency, the national war movement quickly dissolved into small disparate groups, which struggled to re-establish the strength of a mass movement. COSG was central in carrying the flame, and by October 1989 COSG had decided to lead the way towards a new mass anti-conscription movement through a national anti-militarisation conference entitled ‘The Way Forward.'

In a letter to friends of COSG, then national worker Mandy Taylor emphasised that there was an "urgent need for a new organization which [would] raise the public profile around conscription issues."2 She was adamant that it should "not be ECC in drag."3 The notion that the way forward involved accepting the loss of the ECC reflected how far the State of Emergency had annihilated the strength of the ECC during this time.

Conscientious Objection - reaching a critical mass

The upsurge of violent resistance finally forced the state to recognise that it was no longer possible to quell ongoing peaceful protest. Within this context, the ECC unbanned itself and began acting in defiance of its restriction order.4 ECC banners were dusted off and seen flying throughout the country. The police still attempted to suppress these peaceful and sporadic protests, and arrested ten ECC members in Durban for tying yellow ribbons around trees and poles and handing out pamphlets.

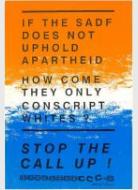

Conscientious Objection was becoming a more acceptable, less intimidating form of protest against the apartheid regime. In 1987, 23 Cape Town men had jointly declared themselves to be COs, and by the following year this number had grown to 143. When 771 men publicly stated their refusal to serve in the SADF on 21 September 1989, what followed was an outpouring of sentiment in favour of Conscientious Objection; a critical mass of support for the anti-conscription movement had been reached and objectors no longer feared possible repercussions (as much). Their plight had finally hit the front pages. The list of 771 COs was distributed nationally and soon an official register of objectors included over 1 000 names.

"(The 771) included [both] English and Afrikaans speaking men...among the group were bishops , priests, doctors, lawyers, teachers, dentists, computer scientists, university lecturers and professors, engineers, journalists, musicians, actors, a company director, students and scholars. The youngest was 17 years old and the oldest 52 years old."5

It was clear that with the restriction of the ECC, the anti-war movement had learned how to work "in more dispersed ways, with different organisations taking on different aspects of the work."6 But it was clear that a centrally coordinated body was necessary.

The 1990s brought with it "a burst of ECC revivalism" as its de-restriction seemed more and more imminent.7 David Schmidt, the new ECC national coordinator, argued:

"Conscription still exists. The dilemma of the reluctant conscript remains unresolved...ECC thus has to adapt or become peripheral...the great challenge of the time is to build organisations across the constituencies defined by apartheid...how do we become truly non racial...apartheid is gradually ending and it is becoming increasingly unacceptable to have race-specific organisations..."8

From 1989 onwards, conscription was slowly phased out. The period of initial military service was reduced to one year. The SADF could no longer cope with the intake, and became more selective about conscripts. By 1993 conscription was officially ended.

The happy ending...

"...ECC remains an exception, not just because we won in the end, but because of the people involved and the spirit we created. I guess we all still hold a candle for it, remembering it with pride..."9

The mandate of the ECC began to shift, necessitated by a move towards a more inclusive, non-racial society. Workshops and parliamentary discussions involved debates about the future of the armed forces. The question of non-racial, universal conscription was central to these discussions. The ECC was a member of the Five Freedoms Forum, an ANC-organised conference held in Lusaka in July 1989. In May 1990 members of the ECC served as intermediaries in an official meeting between SADF officials and strategists and the African National Conference. This meeting focused on fostering a ceasefire on ongoing conflict, absolving the homelands and reintegrating those regions into South Africa, which would effectively re-enfranchise their population groups. The meeting also dealt with the issue of building a non-racial defense force.

"...by the end, there was peace and the South African military people were hanging onto every word Chris Hani said."10

Even during the interregnum, the issue of conscription remained contentious. As long as it existed, the ECC retained its raison d'être. Only when conscription was no longer enforced would the motive for its existence be satisfied. This came in 1993.

Elements of South Africa's new Interim Constitution were clearly incompatible with the Defence Act. For the first time, instead of privileging the military legislation as had been done in the past, the Defence Act would be changed to match the democratic Constitution of the new dispensation.11

By 1994, conscription no longer featured in military legislation, and the ECC officially disbanded. Its greatest success was that it no longer needed to exist.

References

1 Brecht, B. 'General, your tank is a powerful vehicle', Objector, 1 July, 1983, p. 3. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.5.

2 Letter from COSG National Worker to Friends of COSG entitled 'War Resistance Update', 20 October, 1989. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.3.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Interview with ECC National Facilitator David Schmidt, ‘Welcome back ECC', Objector, April-May 1990, p. 11. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL 2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.5.18.

8 Evans, Gavin, Recollections of the End Conscription Campaign, ECC-25 website

9 Ibid.

10 Botha, Neville. Chapter 1, 'Public International Law and the SA Defence Act', ‘The Role of Public International Law in the South African Interim Constitution Act 100 of 1993 and its effect on the South African Defence Act 44 of 1957', Department of Constitutional and Public International Law, University of South Africa. Published in a Compilation of Articles Relating to the Revision of South African Defence Legislation, September 1994