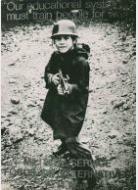

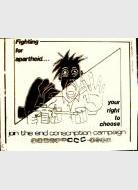

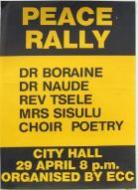

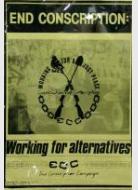

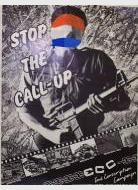

The ECC was a single-issue campaign aimed at bringing an end to the requirement placed on white South African men (and permanent residents) by the Defence Act 44 of 1957 to serve in the South African Defence Force. The ECC soon became a platform for pushing for a more fundamental change in an oppressive regime. It gave many white South Africans a way to participate and contribute towards the anti-apartheid resistance movement.

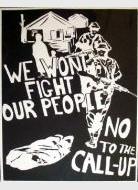

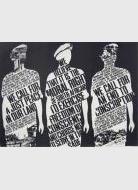

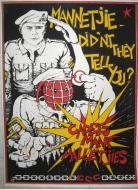

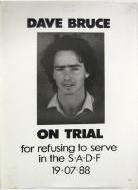

The ‘single-issue' - ending conscription - was inextricably linked to the broader struggle, and, in this sense, the ECC was transformative and its goals multi-layered. Bringing down a system which forced young recruits to participate in a series of internal and external military occupations was central to the ECC. But it was not simply that Conscientious Objectors refused to serve, but rather that they had consciences which "forbid them to fight."1

The ECC had three main goals:

-

to actively campaign against the SADF and its policy of conscription;

-

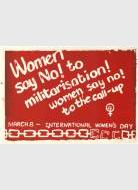

to inform white South Africans about the dangerous influence of the SADF on an increasingly militarised society;

-

and to provide a platform for whites to participate in the struggle.

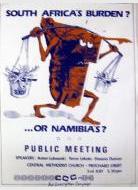

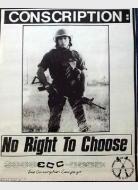

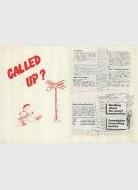

Conscription in any society tends to evoke strong feelings in both directions. Some regarded it as the inherent duty of a citizen to defend his nation's interests by serving in the army. Those against conscription in South Africa varied in their reasoning - some were pacifists, profoundly opposed to the mere concept of war, others were anti-apartheid, fighting for democratic change. Still others were anti-occupation, opposed to the fact that the SADF imposed itself in neighbouring countries like South-West Africa. And others were simply not interested in the political and wanted to get on with their lives. All had one singular, fixed understanding:

They wanted the freedom to choose. They did not want to go to war.

According to the ‘Working Principles of the End Conscription Campaign,' the members were "brought together on the common understanding of the harmful effects of ‘compulsory' military conscription."2

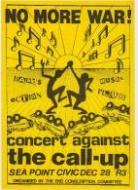

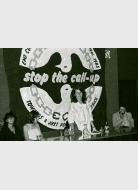

The ECC was closely linked to student politics, providing a relatively safe platform for young white anti-apartheid activists to raise awareness about the SADF, to express their political and moral outrage, and to enable more direct white participation in the anti-apartheid struggle.

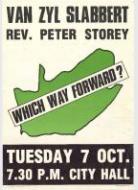

This ability to tap into struggle politics shows how central ideology was in defining the goals of the ECC, but it did not necessarily define the movement. At its heart, this was a political and ideological movement geared for democratic change. The decision to launch a single-issue campaign around the end of conscription was strategic.

"The focus on conscription and working towards its abolition were constructive and legal ways of promoting the entire issue of conscience and the unjust war."3

It was more inclusive than focusing on conscientious objection. Not everyone was motivated by the same thing, but all wanted to protect their right to decide. A paper presented at a March 1984 Black Sash Conference first clarified the nature of the campaign to be formed. According to the working principles of the ECC, supporters were "brought together on the common understanding of the harmful effects of ‘compulsory' military conscription" and the SADF, which it saw as a major source of injustice within South African society.4

The central function of the ECC was to bring about an end to conscription and to educate constituent organisations and the community at large about conscription. Conscription was an important enough issue to define this campaign. One major advantage was that it was legal and did not contravene Section 121 (c) of the Defence Act.

"(It was an important) opportunity for strengthening and broadening the alliances between groups."5

Building on its own momentum, it was hoped that the ECC would "create a coherent voice of opposition to the military within the white community" and serve as a "significant force in undermining the Nationalist Party support base and in building non-racial opposition."6

It was essentially a peace movement, whose agenda was necessarily "very flexible because of the uncertainty of the political situations that might occur."7

This included possible peace initiatives in Angola and the extension of conscription campaign.

The 1983 Black Sash Resolution on Conscription and Conscientious Objection had argued that the growth of militarisation would bring South Africa to its ruin. The perceived need for a conscripted army was based on "the political failure to respond to the desires of the citizens."8

Such failure would require an army engaged in a civil war...

"...in such a civil war, if the state [had] to rely on conscription to man its army the war [was] already lost."9

In direct opposition to Botha's policy of 'Total Strategy', the declaration of the ECC presented a new "total all-out effort of all South Africa's people to bring about democratic government and the relief of the poverty and deprivation suffered by the majority."10

References

1 Memorandum, Broadening the Possibilities for Alternative National Service, Conscientious Objectors Support Group, Johannesburg, July 1988. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A7.7.

2 Rademeyer, Annemarie. Press Release, 'Working for a Just Peace', ECC, 2 April, 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A7.2.1.

3 The Development and Formation of the End Conscription Campaign, Paper presented at the Black Sash National Conference, March 1984, Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA).

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.