"...the news crews are there

for the violent fair

they take their chances with the teargas

...and the SABC transmit

through their satellite

no-one spots the irony

it must have quite a bite

for the government man

who does not understand

that the people overseas

watch all this with ease

on their television..."1

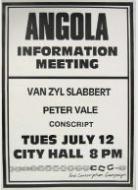

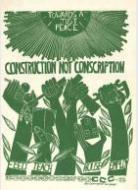

White South Africans faced with the military service were given very few options: serve in the SADF, go to prison, or go into exile. Those who chose to leave South Africa were faced with a large, supportive ex-pat community of South Africans living in the United Kingdom (UK) and Western Europe.

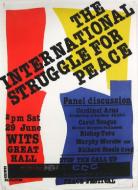

After all, the cause of Conscientious Objectors resonated with peoples throughout the world. By the 1980s, the anti-apartheid movement had taken on global proportions with peace demonstrations and calls on the United Nations to intervene. Economic sanctions and cultural boycotts concretised the world's opposition to Botha's government.

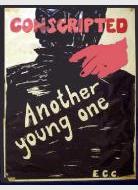

In the first two years of its existence, the ECC was engaged with establishing international solidarity through various means - but mainly through regular written communication. For example, in November 1985 a letter was sent to all organisations with which ECC had previously had contact. This list of approximately 150 groups included non-profit organisations and solidarity groups from the USA, UK, Europe, Africa, Latin America, Australia and the Philippines.2

Whenever major campaigns were launched, such as the Troops out of the Townships Campaign in 1985, the role of international solidarity was taken into account. This campaign was in fact, launched on 17 September, which was the United Nations International Day of Peace. On this day, the ECC had sent a telex to the UN "drawing attention to the launch."3

Many foreign groups responded to the call of the ECC and over 52 messages of support and solidarity were received by the end of 1985, including from groups as far-ranging as Jubilee USA, the Quakers, War Resisters International, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (under Bruce Kent), the Zimbabwe Fellowship of Reconciliation, and Refugees from Chile in Switzerland. Often, these included petitions for help, some more urgent than others. For example, the Student Christian Movement of the Philippines asked for ECC's support in their "struggle against the militarization of their education system."4

In light of this, Laurie Nathan identified numerous areas of weakness in the ECC international work.5 One of these included the need for "more reciprocal contact," especially with "3rd world groups."6 Nathan and Peter Hathorn were invited overseas, garnering more support for the ECC in places like Norway, Germany and Switzerland with press interviews "from sunrise to sunset."7

They were hosted by the People's Movement against War (an affiliate of War Resister's International) in Norway, whose members had recently been convicted for exposing evidence of secret NATO nuclear naval bases in Norway.8

Hence, the ECC was drawn into an international network of anarchist and pacifist peace movements, primarily through the "common commitment to opposing conscription and militarization."9 In Germany ECC representatives met with groups such as Pax Christi, the Green Party, and numerous anti-apartheid and anti-conscription movements. Notably, this included a meeting with the head of the UN Human Rights Commission's Sub-Committee on Conscientious Objection, but the "possible gains" were limited as the Commission would only debate the issue again in 1987.10

In March 1986, Gavin Evans was hosted by the War Resister's League in New York, where he met with a "wide variety of peace, religious and anti-apartheid groups on both the national and local level."11

As state repression in South Africa made it increasingly difficult for the ECC to function, the knowledge of international solidarity and support brought this struggle to the surface. A response to a letter of solidarity from Neil Kinnock, Leader of the British Labour Party, regarded this support as "invaluable."12

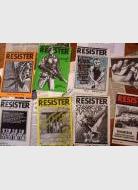

The ECC was bent on its survival during the protracted State of Emergency, unable to participate in international forums. This included the regretful turning down of an invitation by the UN Centre for Human Rights to give evidence to the working group in Lusaka.13

Perhaps one of the most valuable international affiliates of the ECC was the Committee on South African War Resistance (COSAWR), established in both London and Amsterdam, which provided refuge for war resisters seeking political asylum. It was central to organising the worldwide sanctions movement against apartheid South Africa. COSAWR members such as Gerald Kraak and Gavin Cawthra were engaged in carrying out extensive research on the South African military and security forces. This, in turn, served as a corollary for the ECC, whose focus was on finding peaceful alternatives to militarisation. No doubt COSAWR provided support for those who found themselves in exile who sought to engage with the issues that had brought them there in the first place.

As time passed and the political tensions within South Africa intensified, the ECC leadership remained in South Africa, but there is some evidence of an international conscientious objectors network. In May 1989 an international CO Day was held, with an international tour to network with COs from the UK, the Netherlands and the USA. In July 1989, Rob Goldman of the Johannesburg Conscientious Objectors Support Group wrote to Yesh Gvul, an Israeli peace movement engaged in conscientious objection. He spoke of the "many similarities in repression and crisis of conscience between [the] two countries," and did not fail to mention that one of the South African COs, David Bruce, was Jewish.14

The existence of an international solidarity movement against conscription and militarisation in society reflects the value of this issue as a mobilising force.

References

1 Township Beat, Kalahari Surfers, The Eighties, Volume One, Shifty Records

2 Report on ECC's International Contact during the ‘Troops out of the Townships' and ‘Peace Fast' Campaign, November 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A7.1.2.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 National Organiser's Reports to National Conference, January 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.7.

6 Ibid.

7 Letter from ‘Laurie and Pete' (Laurie Nathan and Peter Hathorn), Paris, France, to the ECC, 16 December 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.2.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Letter from Matt Meyer, Acting Chairperson of WRL, to the Catholic Institute on International Relations (CIIR) and the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFR), 12 June 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.2.

12 Letter from David Shandler, for the ECC, to Neil Kinnock, Leader of the Opposition, House of Commons, England, 8 July 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.2.

13 Ibid.

14 Letter from Rob Goldman, CO Support Group National Committee, to Yesh Gvul, 4 July, 1989. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.5.