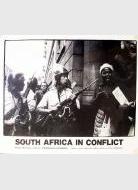

The End Conscription Campaign was an anti-war movement in South Africa that was actively "engaged in the struggle against apartheid."1 Its existence was based on resisting the Apartheid state's use of the military to prop up its regime by conscripting all white South African men to serve in the armed forces.

Despite the magnitude of the Second World War, conscription into the United Defence Force had never before been enforced in the Union of South Africa.2 This changed when the South African Defence Force (SADF) emerged out of the Defence Act No. 44 of 1957, laying out a provision making it possible for the State to enforce conscription; including a predetermined period of time of service and annual obligatory post-service call-ups.3

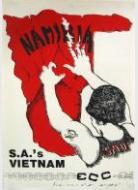

By 1967, the provision for conscription was implemented on a small scale, largely based on the step-up of South African military presence in the liberated front-line countries. It was now more important for the interests of the South African Republic to boost the numbers of SADF units being sent to South West Africa to replace the South African Police (SAP) who had, until then, been the official army in occupied South-West Africa (now Namibia).4

The pressure for increasing the number of troops in South-West Africa was made worse when the SADF crossed the northern border of South-West Africa into Angola in 1974 to "manipulate the independence power struggle in Angola" by backing the guerrilla organisation, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).5

This aggressive action by the SADF had the effect of alienating a growing number of young white South Africans from military participation. By the late 1970s the SADF was forced to respond to the tens of thousands of draft dodgers evading conscription. Reasons for not wanting to become a soldier differed - but no one had the freedom to choose.

Many opposed to conscription were pacifists - opposed to any use of belligerence, regardless of the underlying political motive. Some of these pacifists held beliefs based on religious grounds. Some of the first recognised Conscientious Objectors (COs) involved a group of men who refused to serve on the basic moral ground that war was simply wrong.

This included Anton Eberhardt, who became the first CO to stand trial in 1977. In 1979, the first CO to go public was Peter Moll.6 After his imprisonment, the Conscientious Objector Support Groups (COSG) were set up to provide support to COs and their families.7

Not all Conscientious Objectors were religious. Motives were often heavily influenced by the anti-apartheid struggle movement and the role of the SADF as an occupying force. The first non-religious CO to be charged was Etienne Esery in 1980.8 Aside from the ad hoc assistance of the newly formed COSG, these men were confronting the military behemoth on an individual basis and with no official civil representation.

Aside from reasons based on ideological or ethical grounds, draft-dodgers used any means to avoid the draft. Many enrolled to study full-time university degrees which were then extended past the point of service; others claimed physical or mental incapacity. Notably, a large number of conscript objectors went into exile. Like other exiled elements of the apartheid resistance movement, many in exile unified.

They became mobilised enough to form official anti-conscription and anti-war committees.Committees on South African War Resistance (COSAWR) were established in London and Amsterdam.9

Numerous local groups supported those avoiding the SADF draft, including the alternative/liberal National Union of South African Students (NUSAS).

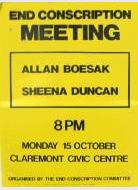

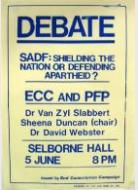

The COSG were closely aligned with the Black Sash, a human rights organisation founded in 1955. At their 1983 national conference, Black Sash patron Sheena Duncan presented a proposal calling for the establishment of a national anti-conscription movement. She argued that although it was illegal to incite anyone to oppose the actions of the SADF, it was not illegal to oppose conscription on ideological grounds.

This was one of the first calls for a unified anti-conscription movement. It had a huge impact for South African COs, who were too often pushed to the margins of their communities, rejected by those family members, friends, colleagues, employers and acquaintances who supported (or feared) the SADF.

COSG served the COs, and became central in the call for a mass movement against conscription.10 This soon led to the establishment of the interim steering committee of the End Conscription Committee.

This development coincided with Operation Askari, South Africa's sixth cross-border invasion of Angola, intended to isolate and undermine the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), the military wing of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO).

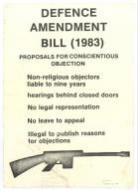

In 1983, the provisions of the Defence Amendment Act were presented before Parliament. Concerned with the increasing militarisation of South Africa, COSG held a national conference, supported by eighteen organisations. Here, a Western Cape COSG Steering Committee was established to coordinate the launch of an anti-conscription campaign.

Its inaugural meeting was held on the 17 November 1983.11 Famous signatories and supporters in the launch of the ECC included Beyers Naude, Helen Joseph, Kate Philip and David Webster.12

Over the course of 1984, support for the anti-conscription movement led to the establishment of the End Conscription Campaign (ECC). The ECC was officially launched in Cape Town at the Claremont Civic Centre on the 15 October 1984, with over 1400 present. The meeting was addressed by Reverend Allan Boesak and Sheena Duncan of the Black Sash.

From the outset, overtly political events and demonstrations related to the ECC were difficult to conduct without violent repercussions. The October edition of Objector (the newsletter of the COSG), which carried the declaration of the ECC as a part of the Declaration Launch Campaign, was banned.13

In Johannesburg, especially after the recent Vaal Triangle uprisings, the state banned all public meetings including the launch of the ECC, so instead a ‘Spring Fair' was held to inaugurate the new peace movement.1

References

1 Letter from David Shandler for the ECC to Neil Kinnock, Leader of the Opposition, House of Commons, England, 8 July 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.2.

2 O'Leary, Derrick. ‘The Border between sanity and insanity: effects of the Border Wars on white South African society', unpublished Honours thesis, Department of History, University of the Witwatersrand, p. 4.

3 Ibid. p. 1

4 Ibid.

6 Handwritten ECC timeline of resistance to apartheid, expansion of SADF and resistance to conscription. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A1.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 'War and Conscience in South Africa: the churches and conscientious objection', Catholic Institute for International Relations/Pax Christi, Russell Press, 1982, p. 39.

10 Letter from Laurie Nathan, Anita Kromberg and Richard Steele, ECC Festival Committee, to Bill Johnston, Episcopal Churchmen, USA. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.1.2.

11 ‘The End Conscription Campaign - A Chronology' (until 1983). Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A1.

12 List of ECC member organisations, October 1984. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A1.

14 Background to the Campaign. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A1.