In October 1984 the apartheid state responded to the Vaal unrest and the almost total boycott of the coloured and Indian elections by sending 7000 South African Defence Force (SADF) troops into the black townships of the Vaal to crush the uprising. They named this 'Operation Palmiet.'

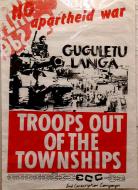

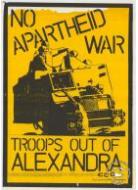

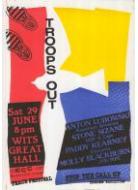

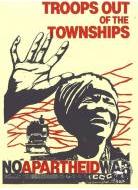

'Troops out of the townships!'

The UDF, and a newly formed organisation called the End Conscription Campaign (ECC), demanded SADF troops out of the townships.

In November UDF affiliates in the Transvaal organised the biggest work stayaway in 35 years. This was done through civics, youth groups, trade unions, and other township-based organisations. The UDF national leadership was in disarray at the time - either in detention or in hiding - and thus unable to meet.

The Transvaal stayaway showed the power of mass action, but it did not stop the repression. Both the mass violence and the government repression spread further.

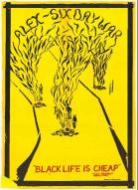

Over the first part of 1985, police and the SADF were deployed in townships throughout the country. Police and the army fired on crowds - often on people gathered to bury the dead from earlier shootings. Leaders and activists were detained. Communities - both in urban and in rural areas - turned on those people seen as working for the government - policemen, "community councillors", government informers, "collaborators". Some were killed; others fled.

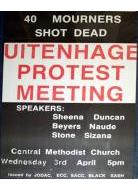

On March 21 - the anniversary of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre - police opened fire on a demonstration in Uitenhage, killing 20 people.

On May 8, three leaders of the Port Elizabeth Civic Organisation, Pebco - Sipho Hashe, Qaqawuli Godolozi and Champion Galela - were abducted and murdered by South African security police.

On June 14, the SADF attacked the homes of people in exile in Botswana, killing 12 people.

In July, four leaders of the Cradock community, Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sicelo Mhlauli and Sparrow Mkhonto (the Cradock Four) were found murdered.

Into the States of Emergency

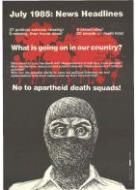

On July 20, 1985, State President PW Botha announced a State of Emergency in 36 magisterial districts, effective from July 21.The Emergency gave police and other officials wide powers to detain people, without revealing their names; it allowed them to ban meetings and organisations; and to prevent media from reporting on unrest and protests

At least 136 UDF officials were known to be detained in the first swoops under the new regulations. Within months the numbers of people detained was in the thousands.

On August 1, lawyer and activist Victoria Mxenge was murdered in Durban.

In August, the largest UDF affiliate, the Congress of South African Students (Cosas), was banned.

Reverend Allan Boesak, president of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, and member of the executive committee of South African Council of Churches (SACC) at the meeting of the Special Committee against Apartheid, said in a statement released on July 24, 1985:

"I cannot begin to describe what has been happening in South Africa since the declaration of a State of Emergency last Saturday. I must say, however, that even before the formal and official declaration in the townships, our people were experiencing a reign of terror conducted by the South African police and the South African Defence Force that was equivalent to a State of Emergency. Even before Saturday, an unofficial curfew was in operation in our townships and many of our people were shot at and killed when they moved around after dark. Even before the State of Emergency, many people were detained without trial, arrested without cause, tortured in the goals and shot like dogs on the streets of our nation. Even before Saturday, we knew of the death squads that were roaming our streets and receiving uncommon protection from the police and the South African government. These are the well-known facts that disturb us about South Africa.

"In the last few months, more than 10 000 people have been detained without trial; of those, some have been released, some have been charged with treason, while others have simply disappeared. We do not know what has happened to those who have disappeared. A pattern is emerging, however, that has persuaded us that what we are seeing is a systematic assassination of the middle level of leadership, not only of the United Democratic Front, but of other organisations as well.

"We do not know exactly who these people are, although we have raised critical questions about the disappearances and deaths of certain leaders in South Africa which have not been answered satisfactorily by the South African government or by its police."

The Government reimposed the State of Emergency every year after 1985, changing restrictions and increasing the areas that it affected. By February 1988 it was estimated that 25 000 people had been detained under the Emergency regulations. By the end of 1987, 1200 people were known to be in detention (it was illegal to publish the names of people detained); of these, 400 had been in detention for over two years.

On February 24, 1988, the minister of law and order published new Emergency regulations, banning the UDF and 16 other organisations. Under this order, the banned organisations were only allowed to take legal advice, and to keep financial accounts. They could not hold meetings, run campaigns, publish media, and hold protests ...

What did living under a State of Emergency mean for a person? What did it mean for people who were known as activists in community organisations and in the UDF?

An article written in 1985 explaining how the State of Emergency could affect those opposing apartheid:

'The police in South Africa have always had many powers. But on Saturday July 21, the state president gave the police even more powers ...

1. They can search your house and take away anything they want.

2. They can stop any meeting.

3. They can arrest you and keep you in jail for 14 days. If they want to keep you longer, the minister of law and order can sign an order - and then they keep you for as long as they like.

4. The head of police can stop the newspapers from writing anything about the places [magisterial districts or geographical areas] under the State of Emergency.

5. The newspapers cannot give the names of people in jail - even if someone says their son and daughter is in jail. The papers can only print the names that the police give them.

6. The emergency laws give the police many other powers. In some places they have started curfews ...

7. You cannot do anything if you are unhappy with the police or other people with special emergency powers. You can't take them to court - no matter what they do to you.

The rights of people in detention

People who are detained under the emergency laws have very few rights:

1. Your family can bring you clothes and some money to buy cigarettes and things like soap. You can't get any books for reading or for study. You can only read a Bible.

2. Your family can visit you - but only if the commissioner of police gives permission.

3. You must get one hour of exercise a day.

4. The district surgeon (doctor) must visit you.

5. They can lock you up all on your own. And if you break their rules in jail, they can punish you. They can fine you - and if they want, they can even whip you.

What to do if someone in your family is detained

1. Finding a detainee: find a good lawyer to help you. The police do not always listen to the families of detainees. If you do not know a good lawyer ... the Detainees' Parents' Support Committee (DPSC) and the Detainees' Support Committee (Descom) ...will help you to find a lawyer. ... Ask the lawyer to find out if your relative is in detention - and at what jail they are holding your relative.

2. Parcels: detainees can get clothes and money - if there is a shop in the prison. If there is no shop, they can get food parcels. Ask the lawyer to help you get permission to take parcels.

3. Visits: you can ask for visits. You must say why you want to visit ...

4. Doctors: if the detainee has a sickness or a health problem, you must tell the doctor at the prison ...

5. Help with money: if the detainee is the breadwinner in your family, speak to an organisation called the Dependants' Conference. They will give you money for rent and food.

6. Start a care group: try to start a care group with the detainee's friends and family. ... For example, the group must tell the detainee's employer about the detention ... They should try to help the detainee's family - and to keep their spirits high'.

Source: Learn and Teach, No. 4, 1985

Detention

Dr Coleman, an official of the Detainees' Parents' Support Committee (DPSC), gave this statement to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on the number of people detained without trial and tortured, including the youth and children:

We come now to detention without trial ... we estimate that at least 80 000 detentions have occurred from 1960 right up until 1990. And most of them actually occurred from 1985 onwards during the States of Emergency.

Children and youth featured very prominently. Again we had tried to make an assessment ... of just how many people were detained and how many amongst them were children and youth. For this assessment, we have drawn from monitoring of our own organisation, monitoring by other organisations and also official information which was obligatory under the Public Safety Act, and certain police affidavits in court revealed a lot of information.

From that we are able to arrive at what we regard as a conservative analysis that there were a total of 80 000 detentions, amongst whom there were about 48 000 youth - in other words 60% of those detentions. This is during this period to 1989.

And within that about 20 000 children, 25%. As far as age is concerned, this went down to as young as seven. Sometimes entire schools, preparatory schools were detained. As far as the gender of detainees, we found that something like one in eight, about 12% of all detainees, were women and girls.

So that we would estimate that 10 000 women and girls were detained in this period (from 1960 - 1989) of whom 6000 would have been youth, 25 and younger, and 2500 would have been children under the age of 18...

Source: Extract from South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Johannesburg Children's Hearing, June 12, 1997