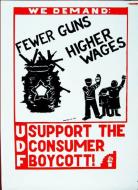

The consumer boycott call came out of community organisations and grew in 1985, spearheaded by the UDF and affiliated organisations. These put forward explicitly political national demands: lifting the State of Emergency, removing police and army from townships, and releasing all political prisoners and detainees.

The boycotts took the form of not buying from mainly white-owned shops, and shops owned by black collaborators with the apartheid regime. In some cases, these were supplemented by local demands such as those for democratic student representative councils and demands aimed at local government. Cosatu added a national demand for political rights for all.

The boycott began piecemeal in a number of small Cape towns. It grew in Port Elizabeth by mid-July, then spread through the rest of the Eastern Cape, and to the Western Cape, the Transvaal, and Natal.

A report on the consumer boycotts in Work in Progress in 1985 states:

The first major urban focus of consumer boycott action, Port Elizabeth, has seen almost total community support for the campaign since it began on 14 July ...

Initiative for the boycott came in early July from a group of township women, which grew from an initial 150 to 700. A number were members of the Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation (Pebco), and the Port Elizabeth Youth Congress (Peyco), but many were unaligned. They were angry about police brutality, the State of Emergency, township conditions, and the infighting between the UDF and Azapo. The community's energy should be directed at the oppressors, they said.

Local community activists and leaders were hesitant about taking boycott action, and this was debated thoroughly ... community organisers felt they could not ignore spontaneous action from their constituents. But they had to ensure it took a constructive political direction, and that organisational strength and depth were improved in the process ...

The UDF and its affiliates took the lead in discussing tactics and calling the boycott ...The group of women were eager to begin the boycott immediately, and there appeared to be fairly widespread support for it. UDF leaders argued that the boycott had to be well publicised, the community mobilised around the call, and clear demands and strategies set out ...

Derrick Swartz, local UDF general secretary, explained: ‘Because we had won the support of the community in the past, many sports bodies, church organisations and community bodies joined the committee. Rank-and-file workers also appeared to give full support.' But, he added, the disappearance of Pebco leadership, detentions, and the organisational demands of the Goniwe funeral meant that remaining leadership was stretched very thin ...

Spreading the word about the boycott was fairly easy, according to Swartz. It was discussed and publicised mainly at funerals, which were often attended by up to 60 000 people, and at mass meetings.- Source: Obery, Ingrid and Jochelson, Karen, 'Industry and government: two sides of the same bloody coin,' Work in Progress, No. 39, October, 1985, pp. 13-14