'"No to councillors!''

Botha’s “new deal” aimed to reinforce this situation by creating “black local authorities” in the townships. Africans living in the townships would be allowed to vote for these authorities – but not for the national government in the Republic of South Africa. At the same time, black local authorities would be paid by, and remain under the control of, the national government’s Bantu Administration Board – white officials appointed by the whites-only government.

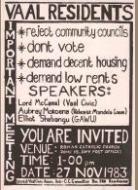

From November 1983, the UDF called for a boycott of elections for black local authorities.

No rent increase for matchboxes

The fight against black local authorities and the Bantu Administration ran side by side with the struggle against increases in rents, electricity, rates, and public transport fares for the black communities.

The black local authorities were expected to pay for most of the “administration” of the townships through raising money from the people who lived in there. At this time, the black local authorities owned all houses in the black townships and rented them out to people – a person classified as African could not own a house in a “white area”. And there were few businesses or factories in the townships, so the authorities did not make money from taxing business. Therefore, the black local authorities tried to make people pay higher rents. They also made money through selling beer through beerhalls owned and run by the Bantu Administration Boards.

In the early 1980s, the black local authorities raised the costs of rent, electricity, water, and transport in many black townships. People began to organise protests against these increases in the cost of living. These protests became one with the rejection of the black local authorities by the UDF. People organised into community groups; these said “NO to community councils, NO to the black local councillors, NO to the Bantu Administration system.”

Black Monday - The Vaal uprising

Before 1984, the apartheid government thought that the black local authorities in the Vaal townships were the “most successful in the country”. The Lekoa Town Council was elected in November 1983, to become the first “elected” black town council in the country. Only 14.7% of the people who could vote actually did vote. (This was well above the national average of people voting for black local authorities.)

Moreover, the Vaal local authorities had for years managed to make a profit – which they did by raising the cost of renting township houses from an average of R11,87 per month in 1977 to R62,56 per month in 1984. (In 1984, this was R10 per month higher than any other township in the country.) In late July 1984 the Lekoa Town Council announced a new rent increase.

A UDF affiliate called the Vaal Civic Association (VCA) mobilised opposition to the rent increase. The VCA had been launched in October 1983, to oppose the November 1983 black local authorities elections.

When rent increases were announced in July, the VCA organised an anti-rent campaign. It issued press statements against the increase, distributed pamphlets, and held meetings in all the affected areas: Boipatong, Sebokeng, Evaton Small Farms, Sharpeville, and Bophelong.

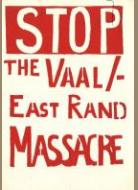

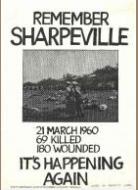

By September 1984, the Vaal Triangle community’s resistance to the apartheid regime came to a head. On September 3, 1984, police opened fire on a march called by the VCA to protest higher rents and rates. People fought back. Violence spread across the Witwatersrand.

The Sebokeng gathering decided to meet on Monday September 3 at the Roman Catholic Church in Small Farms. From there, people would march to the administration offices to express their dissatisfaction.

The Anti-Rent Committee held meetings at the Sharpeville Anglican Church every Sunday between August 12 and September 2.

The council refused to listen, and would not stop the rent increase. Instead the council warned the church leaders in the Vaal that the black local authority would take away their churches’ “site permit” if they continued to hold political meetings in church builidings (the town council issued permits to allow a church to meet on a township plot).

On August 29, hundreds of Bophelong residents met with the community councillors. The council members were armed: the “council mayor”, Mahlatsi, and the “deputy mayor”, Dlamini, carried two guns each.

Angry residents demanded that the mayor answer their questions about the rent increase and a new deposit for electricity. But the police switched off the hall lights, escorted the councillors out of the building, and then fired teargas at the residents in the hall.

Later that night police shot at youths in Bophelong. Violence between residents and police continued over the next week. Then, on the night of September 2, three youths were killed.

On September 3, police stopped marchers from Sharpeville and Boipatong from leaving for Sebokeng, killing several marchers.

In Sharpeville, protesters attacked and killed the deputy mayor, Dlamini.

Police also attacked people in a march from Small Farms, in Evaton. More violence erupted in Sebokeng and Evaton. Many protesters were killed; and the crowd in turn killed two Lekoa councillors and one Evaton councillor.

The government was later to charge a number of UDF and community activists for this violence in the Delmas Treason Trial.

The violence continued, and spread. People attacked the Vaal Administration buildings, beerhalls, and homes and businesses belonging to councillors and police. Police shot, wounded, and killed countless people. They arrested thousands of residents. Police also went to the Vaal hospitals, arresting people who came for treatment for bullet wounds. Others who were shot or injured in the unrest did not go to hospital. In the next five days more than 40 people died: police killed over 90% of these.

After September 3, almost all of those associated with organising the rent protest were arrested or went into hiding away from the Vaal.

Source:Jochelson, Karen. 'Rent Boycotts: Local Authorities on their Knees', Work in Progress, No. 44, September/October 1986.

Black Christmas: no reason to celebrate

Across the Transvaal, the UDF and its affiliates called on people not to celebrate Christmas. Popo Molefe, the general secretary of the UDF, asked people to call for the Black Christmas period to last from December 16 to 26.