In the run-up to the launch of the UDF in 1983, regional committees were formed in the Transvaal, Natal, Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Border region. The Border region of the UDF was formally launched in December 1983. The story of the formation of the UDF’s Border region shows the links between people’s daily lives and struggles, the formation of mass-based, grassroots organisations to address these problems, and the creation of the UDF.

The Border region covered the area called the Ciskei. The white regime had set up the Ciskei as a “bantustan” or “homeland”: in the 1970s, Xhosa-speaking Africans who lived in urban areas but did not have jobs there were forced to move to the Bantustan. Factories located across the border in the “white republic” hired workers who would travel every day to work from homes in the Ciskei. In line with the white Republic’s plans to create “independent homelands” for blacks, the Ciskei had been declared an “independent” country in December 1981.

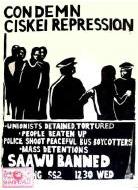

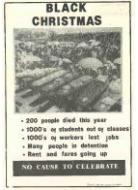

In 1983, residents and workers in the Ciskei organised mass protests against the costs of buses and trains to get to work “over the border” in South Africa. These boycotts were organised by the new trade union, the South African Allied Workers’ Union (Saawu), and local residents’ organisations working together. The military head of the Ciskei, General Lennox Sebe, sent troops to attack residents protesting bus fares. Troops opened fire on crowds outside train and bus stations, killing and wounding many people.

UDF official Graeme Bloch describes how the UDF responded to the Mdantsane bus boycotts, both in the Border region and by mobilising national support:

“The East London support campaign grew out of Sebe’s direct assaults on a major UDF affiliate, Saawu. Surely, the anti-Ciskei campaign was directly within the UDF’s mandate, and fell squarely within the decision to oppose artificial bantustan divisions, of which the Koornhof Bills were one manifestation.

… [I]n Cape Town, in fact, it was the UDF-affiliated detainee support committees which first focused attention on the need for an active response … Thus the UDF tested its ability to generate a national response, it exposed locally and internationally Sebe’s atrocities, and it successfully created a breathing space for the organisation to consolidate.

… The very growth of the UDF Border region, which recently held a highly democratic and vibrant AGM, has much to do with the important successes of earlier UDF campaigns."

- Source: Bloch, Graeme. "The UDF: A National Political Initiative," Work in Progress, No. 41, April, 1986, p. 26

The Ciskei dictatorship tried to smash the bus boycott protests by banning the main trade union involved, and detaining and torturing the union’s leaders. At this stage, the newly formed UDF organised a national campaign against this repression, as well as continuing to mobilise people in the Border region against the Ciskei “homeland”.

(For more about the role of trade unions in the UDF, see the Trade Unions theme.)

Organising resistance during the Mdantsane bus boycott

“On July 18 1983, a boycott of the partly government-owned Ciskei Transport Corporation (CTC) buses started in Mdantsane, Ciskei, in protest at an 11% fare increase. The boycott lasted several years and involved shooting of and assaults on commuters by the Ciskei security forces backed up by vigilantes, in attempts to force commuters to use the buses … When the boycott started, commuters initially walked to work in large groups, from Mdantsane across the Ciskei border to East London, a distance of about 20 kilometres. These groups effectively became mass demonstrations against the bus company. Later, more use was made of private taxis and trains.”

Source: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 3, Chapter 2, Subsection 16.

Within days, the boycott elicited a violent response from Ciskei authorities. Security forces and vigilantes set up roadblocks in Mdantsane, and there were reports of commuters being hauled out of taxis and ordered onto buses. On July 22, 1983, five people were shot and wounded by Ciskei security forces at the Fort Jackson railway station. On July 30, a man was attacked and killed by vigilantes while walking near the Mdantsane Stadium, used by vigilantes as a base. On August 3, a state of emergency was declared in Mdantsane and a night curfew imposed. Meetings of more than four people were banned and people were prohibited from walking in groups larger than four. The following day Ciskei forces opened fire on commuters at three Mdantsane railway stations.

In the dark, early winter morning of Thursday August 4, Mdantsane commuters started walking up the small hill to the railway line that ran alongside Mdantsane and the three stations of Fort Jackson, Egerton and Mount Ruth that served the township. The state of emergency had been declared the evening before and the first nightly curfew had just ended at 4am. Many commuters were probably still unaware of the emergency or the curfew. They were met at each station by a human blockade of armed police and soldiers, supported by vigilantes armed with sticks and sjamboks (whips). The security forces apparently had one aim: to get the commuters back onto the buses. Within an hour, commuters had been shot at all three railway stations.

Valencia Ntombiyakhe Madlityane told the Truth and Reconiciliation Commission that she was shot by soldiers at Mount Ruth station at about 5am after she ignored police orders to use a bus instead of the train. At least three people died in the incident. At 4:20am union employee Kholeka Dlutu heard shooting at Egerton, where commuters also died. Shooting was also reported at Fort Jackson, where some injuries were reported. All in all, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission testimony, “at least six commuters died and dozens were injured. The fact that shooting happened at more than one station points to a co-ordinated security force operation with orders to stop commuters from catching the trains at all costs. While police later claimed they were attacked, attempts to prosecute commuters for such attacks failed and it seems unlikely there would have been similar attacks at all three stations at the same time.”

Dlutu said she heard shooting and went with her aunt to see what was happening. She stated in an affidavit to the TRC:

“Somewhere near the church nearby a corner house, on the way to Egerton railway station, we came across a girl who was bleeding from the thigh and screaming. She alleged that she had been shot by the police. We proceeded and saw many people in an open veld standing opposite Egerton station, and a smaller group of people, some wearing brown overalls and some wearing other police or army uniform, standing on the opposite side nearer the station. The two groups were facing each other. Whenever the commuters moved towards the station, the other group, to whom I shall collectively refer as the police, would advance as if to meet the first group halfway, causing the commuters to retreat, some of whom ran into residential yards.

At that stage, visibility was poor, but the action described above went on for so long that the light gradually improved. Meanwhile, some of the commuters were managing to escape and reach the railway line by taking devious routes and crossing the railway line. Later, when the police advanced once more, the commuters did not run but shouted out that they were not at war with the police and only wanted to get to the railway station so as to board trains to East London.”

- Kholeka DlutuSource: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 3, Chapter 2, Subsection 16.