[For more information on individual posters, click or hover over images]

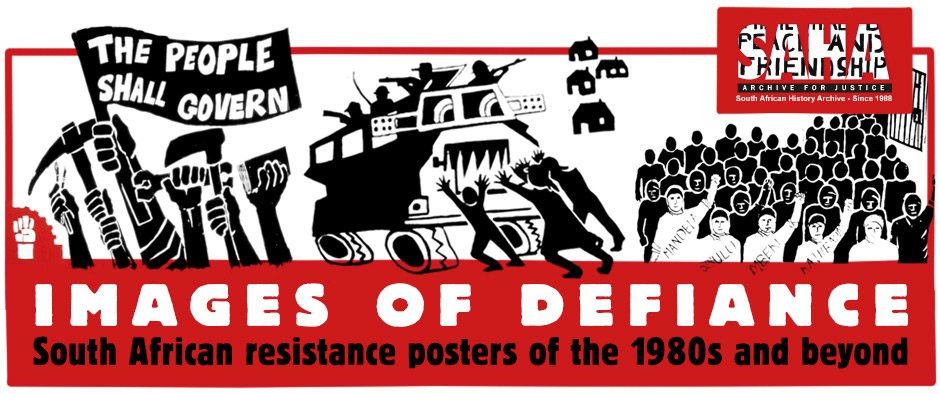

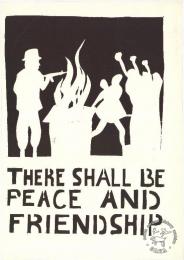

The struggle for democracy and non-racialism in South Africa has been a long one. For more than 300 years, since the arrival of the first colonialists, South Africans fought in various ways against the theft of their land, racial oppression and economic exploitation. But it is the 1980s which will go down in history as the decade of mass organisation. By the last days of 1989, this organisation had become so resilient and strong it was clear that the decisive shift from the politics of resistance to the politics of transformation was about to take place.

Strands of resistance

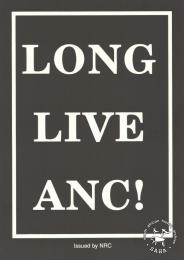

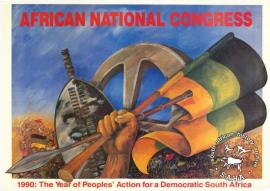

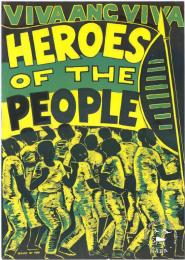

The British colonial authorities handed power to the white settlers of South Africa in 1910. On the 8 January 1912, the African National Congress (ANC) was founded (under its original name of the South African National Native Congress). The ANC aimed to unite all existing black organisations working for a non-racial society into one strong force.

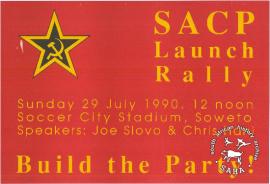

A second organisation, the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), now called the South African Communist Party (SACP), was founded in 1921. Although initially located among white workers, the party soon turned its efforts to mobilising the much larger black working class, linking the struggle against economic exploitation with the fight against national oppression.

Over time, the ANC and the SACP, together with the nascent black trade unions, formed a close working relationship in the struggle for a national democracy.

Over time, the ANC and the SACP, together with the nascent black trade unions, formed a close working relationship in the struggle for a national democracy.

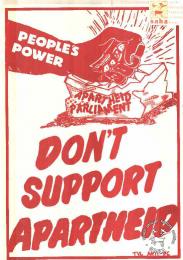

In 1948, the National Party was voted into power. Their first priority was to stem the tide of resistance to segregation and racial discrimination. In 1950, the Suppression of Communism Act was passed, effectively banning the Communist Party. The Act also cast a wider net — it was phrased in such a way as to allow the state to brand as communist anyone who attempted to change the prevailing political situation. The National Party also moved rapidly to introduce apartheid, a legally-enforced policy of racial segregation and discrimination.

Apartheid is introduced

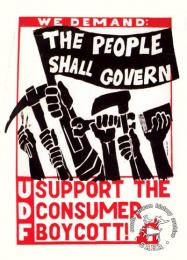

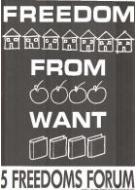

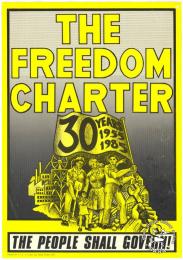

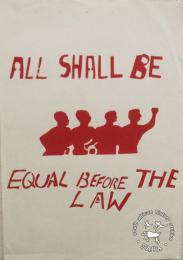

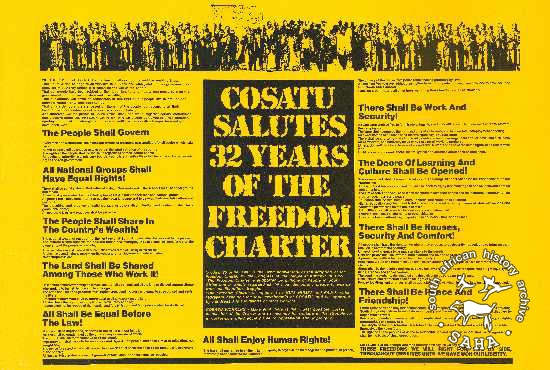

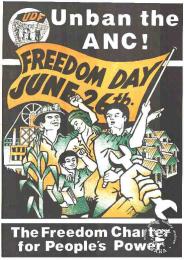

But while the 1950s entrenched racial segregation in South Africa, that decade also marked the beginning of intense and sustained popular defiance to institutionalised racism. The ANC Youth League, under Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, began the first Defiance Campaign, involving thousands in mass refusals to obey the new apartheid laws. This momentum led to the Congress of the People: on 26 June 1955 delegates from all over the country put forward the demands in the document known as the Freedom Charter.

The government could not permit this militancy. On 21 March 1960 police opened fire on a peaceful crowd in Sharpeville, killing 69 people. When the ANC called for a national stayaway to protest this massacre, the government banned both the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) (formed by elements that broke away from the ANC in 1959). The ANC turned to a long 30 years of underground work.

The 1960s also marked the beginning of the armed struggle. After so many decades of peaceful resistance in the face of state violence, the ANC concluded that force must be met with force, and formed its military wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the Spear of the Nation.

The 1960s also marked the beginning of the armed struggle. After so many decades of peaceful resistance in the face of state violence, the ANC concluded that force must be met with force, and formed its military wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the Spear of the Nation.

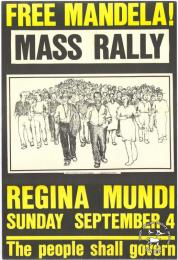

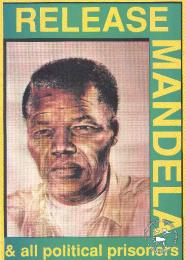

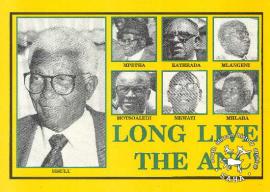

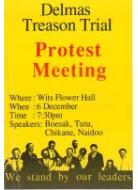

In October 1963, leaders of the ANC and MK were arrested at Lilliesleaf farm in Rivonia near Johannesburg. When they were finally brought to trial, Nelson Mandela, already serving a sentence for leaving the country illegally, was charged along with them. Eight of the accused were sentenced to life imprisonment.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s the apartheid government appeared to have finally enforced an unwilling quiesence. The ANC, SACP and PAC were banned. MK continued its preparations for a sabotage campaign, but mass protests were muted. The emergence of black trade unionism in 1973, and of black student protest, seemed but a minor crack in the facade. That apparent passivity ended on 16 June 1976. Police opened fire on youths protesting apartheid education; within days, an uprising spread throughout the black South African townships. In the months that followed, thousands of protesters were killed by the police, others were jailed, and still others left the country to join the ANC, MK and other exiled organisations. As time went by, the anger and militancy were transformed into organised mass political protest.

The people re-organise

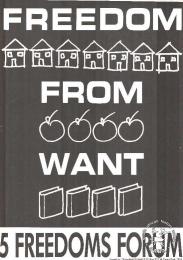

The mass movement of the 1980s brought together a number of political and organisational strands. Building on the militancy of the 1976 youth uprising, it revived the vision of a united non-racial democratic South Africa embodied in the Freedom Charter. The demands of the Freedom Charter gave ideological direction and organisational unity to the spontaneous anger generated by the repression that followed 1976.

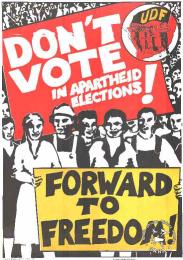

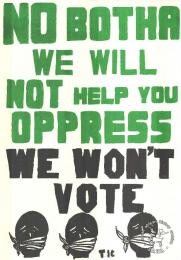

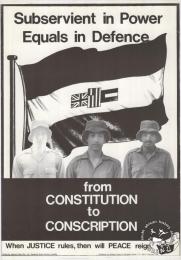

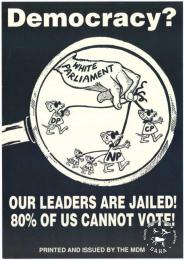

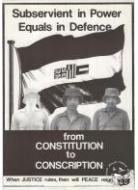

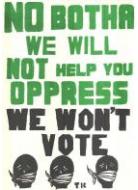

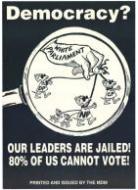

This focus on the Freedom Charter also renewed mass interest in the Congress movement, led by the ANC, then entering its third decade as a banned organisation. Meanwhile, the state tried a reformist strategy, introducing a new constitution that created coloured and Indian chambers in the South African parliament, but still excluded Africans from central political participation and firmly retained white control.

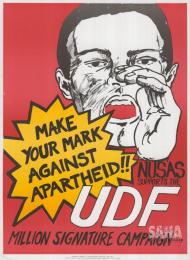

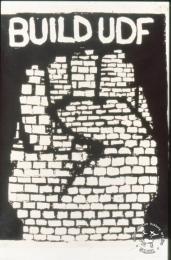

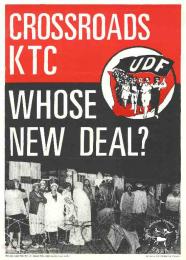

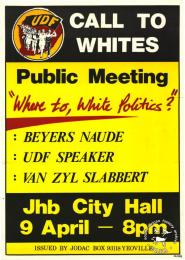

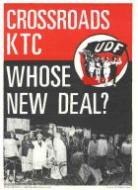

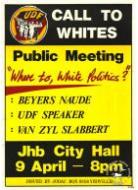

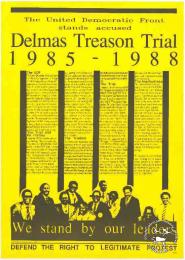

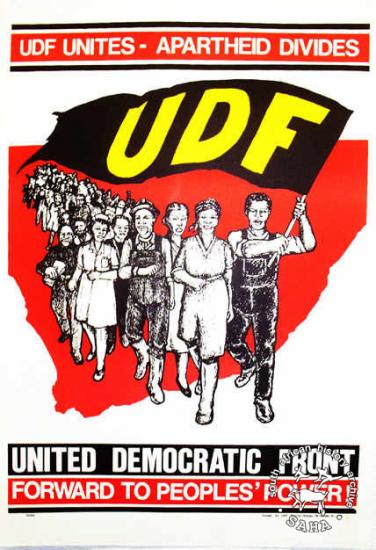

The mass movement responded by forming the United Democratic Front in August 1983. The UDF brought together more than 600 youth structures, student organisations, trade unions, church groups, civic organisations, women's groups and political organisations. It identified clearly with the ANC and the Congress tradition. Old Congress structures like the Transvaal Indian Congress, which was never banned, joined the UDF along with new organisations which emerged for the first time in the 1980s. The UDF umbrella gave these groups a political focus directed at central state power, and also an organisational capacity and impact far beyond the individual potential of each structure.

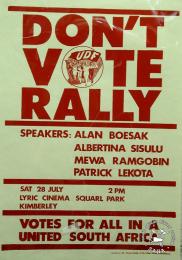

This capacity was demonstrated in the campaign to reject the tri-cameral parliament and the black local authorities structure. Using slogans such as 'Votes For All', and through boycotts of elections for the tri-cameral parliament and black local authorities, the UDF convincingly demonstrated the determination of South Africa's people to fight token solutions, and to demand access to real political power.

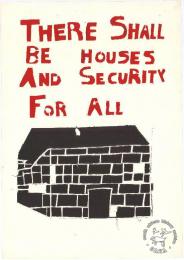

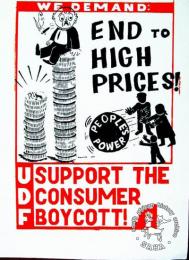

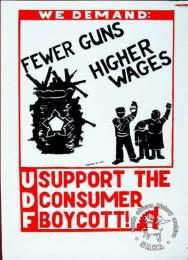

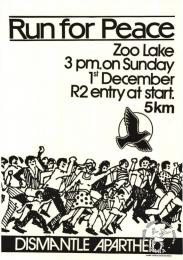

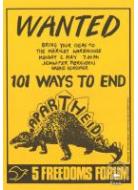

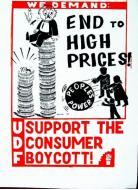

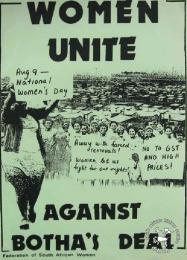

Mass organisation — civics, youth and women's structures — developed fast. Nonviolent forms of political protest mushroomed: boycotts, stayaways, demonstrations and marches backed up demands connected with local issues such as rent increases, education and health problems, corruption in local authorities and transport shortages. The UDF convincingly linked these local grassroots issues to broader national political demands.

Mass organisation — civics, youth and women's structures — developed fast. Nonviolent forms of political protest mushroomed: boycotts, stayaways, demonstrations and marches backed up demands connected with local issues such as rent increases, education and health problems, corruption in local authorities and transport shortages. The UDF convincingly linked these local grassroots issues to broader national political demands.

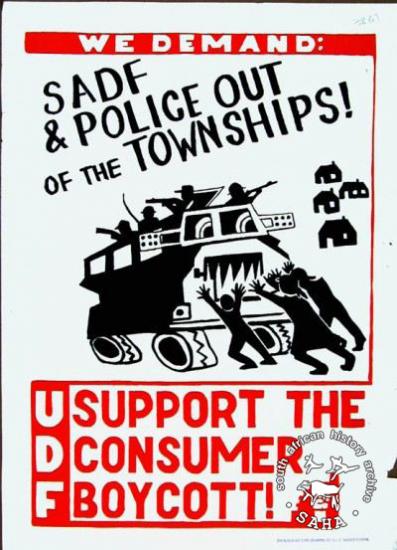

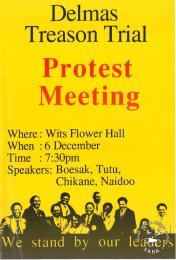

In September 1984, a year after the founding of the UDF, police fired on a protest march in Sebokeng. The townships erupted again. The people turned on those they viewed as state puppets, such as community councillors, township administrators and the police: their houses were burned, they were killed or had to flee. Army troops were sent in to quell the uprising, but they used a level of violence that simply refuelled people's anger. Both the ANC underground and the legal structures of the UDF worked to give form to this outburst. Tactics like consumer boycotts and mass stayaways were wielded with immense power. Many of the discredited black local authorities collapsed.

The State Crackdown

In July 1985, the state declared a partial State of Emergency, banning all public meetings, arresting and detaining activists, and sending troops to occupy townships. But while repression disrupted the activities of national organisations, it also forced the process of mass mobilisation to become local and decentralised. New organisational structures, such as street, zone and block committees sprang up in the townships. These structures brought a new rallying call for people's power — empowerment of all the people from the street level up.

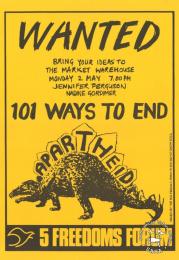

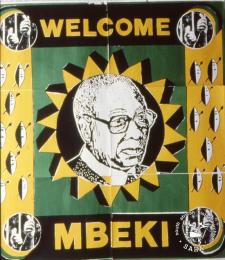

The state imposed successive States of Emergency. Although increasingly forced underground, activists replied with ongoing political campaigns — against the bantustan system, the tri-cameral parliament and black local authorities, against continuing repression and economic exploitation, for the unbanning of organisations, for votes for all in a united South Africa. The Emergency wrought havoc on the economy and tightened the noose of international disapproval. South Africa's isolation became almost complete. In the face of this, the white monolith began to crack, and the first of a series of influential whites made their way to Lusaka to meet with the ANC and discover what this illegal but ever-present force had to say about the future.

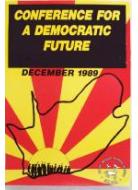

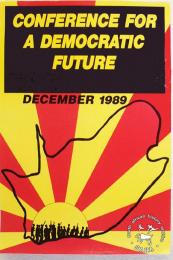

By early 1989, the Mass Democratic Movement (a general term used to identify the organisations which could not organise openly under the State of Emergency) called for a second Defiance Campaign to demand that troops leave the townships, an end to the Emergency, and the unbanning of popular opposition organisations. At the heart of this campaign lay the call to unban the ANC.

As the decade drew to a close, it was clear to all, including the apartheid government, that without the ANC there would be no solution to South Africa's problems.

On 2 February 1990, the regime unbanned the ANC, the SACP and the PAC. Nine days later, on 11 February 1990, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was freed after 27 years in prison.

The ten fighting years of the 1980s had brought the South African people closer to freedom than ever before.