[For more information on individual posters, click or hover over images]

`To speak to the people by means of posters, to address that large number who do not even read cheap newspapers, is a revolutionary method...'

From The Palette and the Flame a book of Spanish Civil War posters

Shattering the silence

As the sun set and darkness crept into the dusty hall, people around us lit candles so that we could continue printing. While pulling the squeegies across the mesh, we noticed that local residents had crowded outside every window of the long, narrow room, trying to see what was happening. When we went out into the fading evening light to wash the screens off at the nearby communal tap, youngsters followed us, looking, touching, asking questions.

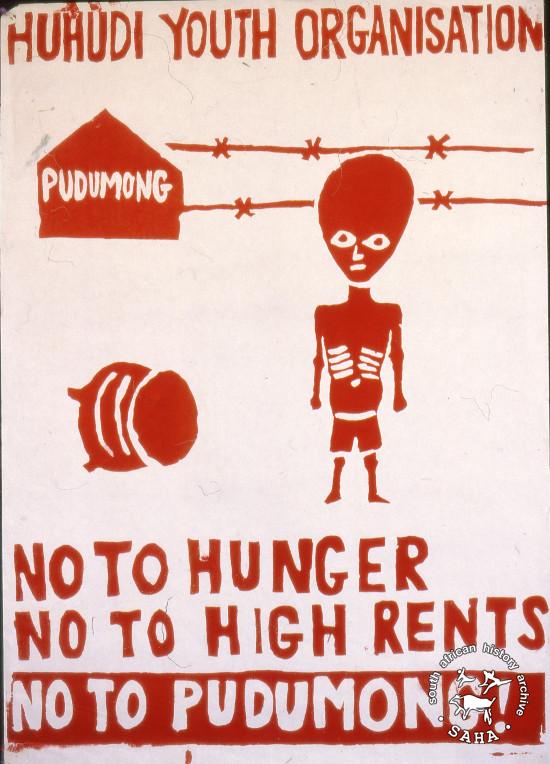

This was the Lesedi Silkscreen Workshop (lesedi meaning light) in Huhudi, a black township in the Northern Cape that was fighting for its very existence. The government wanted to move the people to one of apartheid's bantustans, a backwater that the people of Huhudi saw as a wasteland of starvation and death.

Members of the township's youth organisation and civic association had come to the Screen Training Project in Johannesburg to make posters to take back to their community. But one of STP's aims was to encourage communities to set up their own production units. We wanted people to produce, in their own areas, the posters and T-shirts that proclaimed their struggle for freedom. So we welcomed the request of the Huhudi community that we should help them set up their own workshop.

The people of Huhudi started printing posters at the Lesedi workshop in 1985. The reaction of the state was swift. The workshop was petrol-bombed, some activists were detained, others fled the country. The States of Emergency imposed after 1985 eventually forced Lesedi to close.

The attack on the poster workshop was part of a general clamp-down on political activity in the township as the state tried to force the residents to move and the people resisted. But the Huhudi community stood firm. Finally, after years of struggle, the government conceded that Huhudi could remain where it was. People's power had won, though not without cost.

The poster movement in South Africa

The story of political posters in the 1980s is the story of the people and organisations that produced them. The posters in this book were not produced by an artistic elite, but by the people of South Africa. They reflect a grassroots vision of the struggles of the present and hopes for the future. They were produced in the face of enormous odds, ranging from a basic lack of skills and resources to outright bannings, detentions, and sometimes death.

The South African government force-fed the ideology of apartheid to all South Africans, black and white. The education system, the church, the military, the electronic and print media, and various cultural organisations, together churned out a steady diet of racist and supremacist theories. Even institutions not controlled by the state bowed to the constraints of the apartheid system: newspapers which questioned apartheid were either censored or banned, private educational institutions were closed down or denied the funds to operate.

At the same time, apartheid policies deprived communities of the opportunity to produce their own media. Bantu education left most people illiterate or semi-literate. With few exceptions, formal arts training was restricted to a small, privileged, and overwhelmingly white, middle class.

Deliberate state impoverishment and underdevelopment of townships and rural areas ensured that resources for media production —even such basic requirements as electricity —were out of reach for most communities.

The emerging grassroots community structures of the 1980s used posters, banners, leaflets, T-shirts, lapel badges, flags, stickers and graffiti in their fight to loosen the grip of apartheid ideas. By producing their own media, however unsophisticated, organisations claimed their right to be heard.

The posters in this book demonstrate their determination to win that right. Each challenges the state's attempt to hammer people into ideological submission. As a whole, they paint a picture of the popular struggle which reached its peak with the Defiance Campaign of 1989, leading finally to the unbanning of the African National Congress and other organisations, and the release of Nelson Mandela and his fellow political prisoners.

Posters and poster culture in South Africa

Since the beginning of the 20th century in South Africa, posters have been used for commercial advertising and political propaganda. The most widespread political use was of the 'portrait of the candidate' type for whites-only elections.

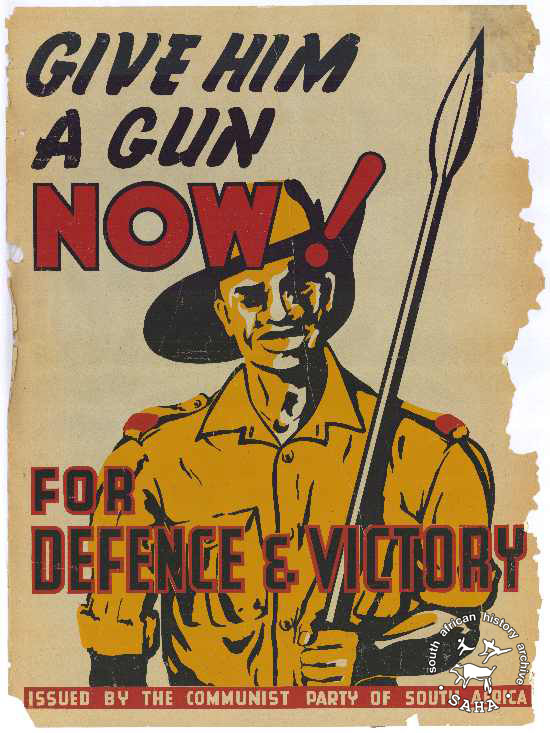

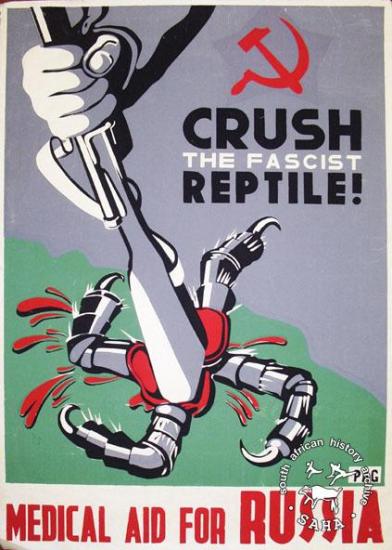

During the Second World War, the government followed European trends of using posters to stir up patriotism and to raise money. But posters were also produced by the Communist Party of South Africa and by Medical Aid for Russia, a support group which collected money for the Soviet Union's war effort.

During the Second World War, the government followed European trends of using posters to stir up patriotism and to raise money. But posters were also produced by the Communist Party of South Africa and by Medical Aid for Russia, a support group which collected money for the Soviet Union's war effort.

The extent to which posters were used as part of the very intense anti-apartheid struggles of the 1950s is not clear. It would seem that placards, banners and leaflets were more common.

Public mass protest and the use of graphics declined after the suppression of the ANC and PAC in 1960. By the end of that decade, the major source of poster production appears to have been university campuses. Student politics in the 1960s, especially among whites, reflected aspects of the militancy of campuses in Europe and the United States, which included the use of political posters. While distribution of these posters was mostly restricted to the campuses, their subject matter often dealt with major national issues. But one of the only known collections of these posters was destroyed in a mysterious fire which gutted a floor of the students' union building at Wits University in the early 1980s.

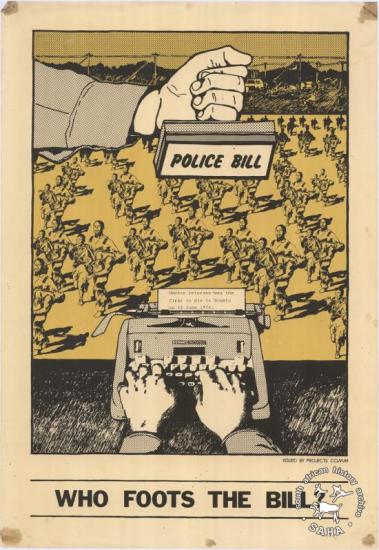

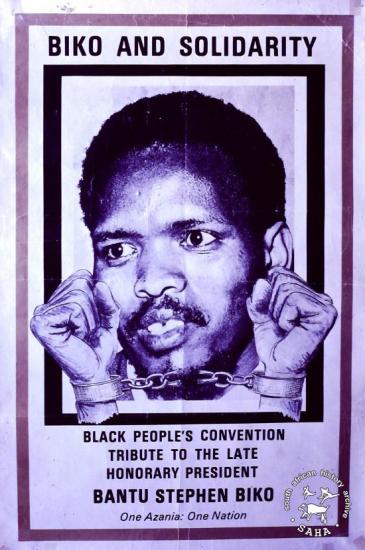

In the 1970s, trade unions re-emerged as a major force in South Africa. But they only began to use posters regularly in the latter part of the decade. Other organisations occasionally produced posters during this period. The black consciousness groups, the most vocal internal political force at the time, appear not to have used the medium much. The student uprising of 16 June 1976 seems to have relied upon individually-made placards and banners rather than printed posters. On the other hand, several posters commemorated the death in detention in 1977 of black consciousness leader, Steve Biko.

Therefore, although posters were used in various ways in the past, the real era of South African posters began in the 1980s with the formation of the Screen Training Project (STP) in Johannesburg, and the Community Arts Project (CAP) Media Project in Cape Town.

Posters from exile

Posters supporting the liberation struggle in South Africa have been produced throughout the world to raise international awareness of the inequities of apartheid. But in 1978, just across the border from South Africa, a group of exiled South African cultural workers began to print posters with a different purpose.

Medu Art Ensemble was formed in Botswana to use art to give voice to the growing struggle of the people 'at home'. Medu designed posters for distribution inside South Africa, to be used by organisations directly confronting the apartheid state. Medu called for the South African mass movement to develop silkscreening as a communications technique. Silkscreening, they said, requires relatively little equipment or capital outlay, does not need electricity, and the skills can be easily taught.

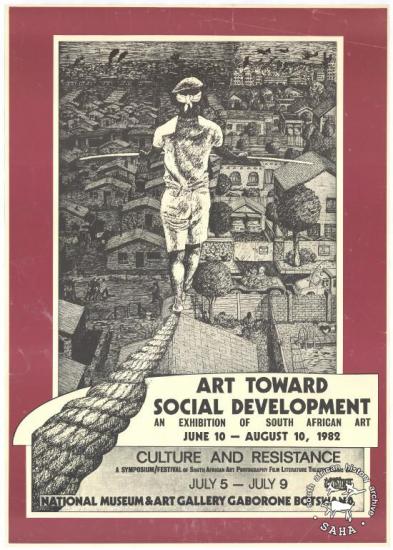

In July 1982, over 5 000 cultural workers from South Africa participated in the Medu-organised Culture and Resistance Festival in Gaborone. They carried back with them the conference theme: political struggle is an unavoidable part of life in South Africa, and it must therefore infuse our art and culture.

After the conference, the South African state banned Medu posters within days of publication. Distribution crumbled as people risked years in jail for smuggling posters across the border.

At the same time, activists had formed silk-screen workshops in South Africa which produced and distributed posters far more effectively in response to immediate demands. Medu was no longer needed in the same way.

At 1 am on 14 June 1985, South African army units crossed the border and attacked Gaborone, killing 12 people. Among the dead were leading graphic artist and Medu official Thami Mnyele, and Medu treasurer Mike Hamlyn. The homes of several other Medu artists were destroyed. Remaining South African members of Medu left Botswana, or went underground. Medu ceased to exist.

Silkscreening in Johannesburg

In 1979 the Johannesburg-based Junction Avenue community of cultural workers silkscreened posters for the Fattis and Monis pasta boycott, supporting workers dismissed during a strike. The group went on to make posters for other worker struggles, including the red meat strike in 1980 and the Wilson-Rowntree sweet boycott of 1981. Also in 1981, a community-based labour support structure, Rock Against Management (RAM), commissioned artists to produce posters challenging the proposed celebration of 20 years of South Africa as a republic under a white minority government.

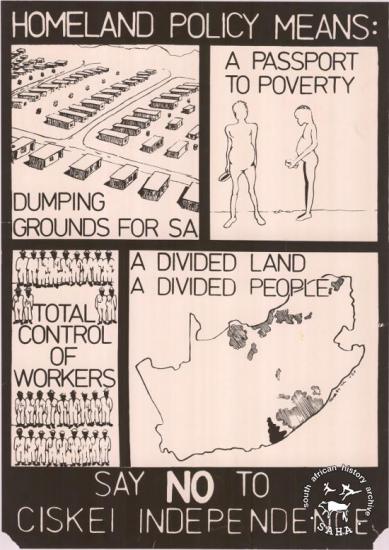

Out of this activity, a part-time voluntary workshop was born, providing in-house training, printing posters and T-shirts, and offering training to community organisations. Their first poster attacked the imminent 'independence' of the Ciskei, one of the apartheid-created African 'homelands'.

In 1983, the UDF amalgamated over 600 grassroots and civic organisations into a national anti-apartheid body. The Front backed a proposal that the part-time workshop become a full-time facility serving all UDF affiliates. In November 1983, the Screen Training Project came into being.

STP aimed to train members of community organisations in silkscreening techniques, to help set up workshops around the country, and to provide production facilities for organisations to produce their own media on STP's premises.

Soon a steady stream of activists from all over the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and parts of the Cape was passing through the workshop, producing thousands of posters, T-shirts, badges and banners. The demand stretched the project's resources — human and technical — to the limit.

The quality of posters produced in the workshops was often atrocious. Hand-lettered and hand-painted stencils, and printing carried out at breakneck speed by absolute beginners, led to all kinds of streaking and blotching.

But there were sound reasons why the demand remained. Silkscreening allowed for full participation by the newly recruited membership of UDF organisations, involving up to 20 people at a time in preparation and printing. The process permitted short 'runs' at relatively low cost, which proved perfect for publicising hundreds of local meetings and activities.

The new project also attracted unwanted, but not unexpected, attention from other quarters. After only six months of operating, STP workers arrived at the workshop to find the gates forced open, furniture and screening equipment wrecked, and the project's brand-new photocopier smashed. The vandals were never traced.

In 1984, security police arrived at the project's new premises and confiscated a large number of posters. In the same period, the state banned a T-shirt produced at the workshop by activists from the Eastern Cape.

However, the same worker was detained two months later. The police claimed that he was 'the co-ordinator of the so-called screen programme, an organisation responsible for the printing and distribution of subversive literature in the Johannesburg area, and also actively involved in the training of Black Youths of the Soweto Youth Congress and the Alexandra Youth Congress.' Five more STP workers were detained over the next few months.At the start of the first State of Emergency in 1985, a worker from STP was detained for four months. No reasons were given. In 1986, on the first day of the second Emergency, police waited at the door of STP from 4am. But project staff were expecting this new crackdown, and had gone into hiding.

These acts of repression forced STP underground. The project found secret offices, and could not advertise its services to the community. Although STP was set up primarily as a training workshop, staff were so tied up in production that the training component was neglected. Community organisations remained unable to produce posters without the assistance of STP staff. With STP in hiding, silkscreen production declined.

STP re-emerged as the Media Training Workshop (MTW) after the unbannings of 1990, but with the disbanding of the UDF in 1991 the project's future remains uncertain.

Printing in Cape Town

In the wave of interest generated by the Culture and Resistance Festival in Botswana in mid-1982, a group of cultural workers resolved to establish a screen-printing resource centre based at the Community Arts Project in Cape Town.

A year later, a simple workshop was equipped — with a printing table, drying lines, a bathtub, an exposure box and a huge vertical camera dis-

carded by a printing company. Although a few posters were produced — the CAYCO launch poster, and posters for a few CAP events — the workshop was hardly used.

At this point, a few members of the original group introduced a series of weekend workshops for community organisations, unions and educational projects. They invited all progressive organisations to make their posters with CAP's assistance.

The slow trickle of users became a flood with the launch of the UDF. By late 1983, the workshop was in use day and night. A used screen left the printing table only to be replaced by the next in line; posters were force-dried with hair-driers for instant distribution; and the floor of the washout room was constantly flooded.

The south-easter gusting through the workshop every time the door opened only made matters worse, gluing wet posters together as they hung on the drying lines, and covering everything with sand. Frequent outbreaks of hilarity may have owed something to the heavy fog of ink and thinners.

This was only the start of an almost uninterrupted flow of work — bannings, restrictions and States of Emergency notwithstanding. When organisations could no longer hold public meetings, they organised fun-runs, cultural evenings, fetes and snack-dances — these needed posters too.

The workshop also printed stickers, buttons and T-shirts. T-shirts in particular became so widespread as 'walking posters' that CAP created a separate facility to produce them. (The state felt obliged to counter the popularity of such T-shirts and passed a short-lived law banning them.) The workshop evolved further to incorporate banner-making and, to a lesser degree, fabric-printing.

But CAP, like STP in Johannesburg, encountered problems. Daily requests for short workshops, technical assistance, and use of the facilities, swamped long-term training objectives.

Both STP and CAP found that training programmes had to be tailored to 'fit the case' in every situation, taking into account language, local conditions, schooling, political experience, technical experience, and many other disparate factors. 'Blueprints' for training were useless.

Further, training must be backed up by access to resources, and should meet the organisation's needs. Newly acquired skills, if not practised, are quickly lost. Both projects found that they trained fewer people more slowly than initially anticipated.

Unlike STP, CAP was not forced to go underground. It was subjected to a degree of harassment, but continued operating openly. Unfortunately, like so many other anti-apartheid service structures, CAP has found itself starved of resources in the new political climate following the unbannings of 1990. Its future, therefore, is also not certain.

Posters in Natal

While posters were produced in Natal, there was no central poster workshop similar to CAP or STP. After the formation of the UDF, a broad media grouping was set up which was linked to the community newspaper Ukusa. Fine arts students working with this grouping helped design posters; some were commercially printed, but most were silkscreened at the University of Durban-Westville (UDW).

The UDW Students' Representative Council, working with fine arts students, also set up small silkscreen workshops in the community, primarily in the Indian areas of Chatsworth and Merebank.

Posters silkscreened at the University of Natal, Durban, were mainly for student organisations such as COSAS, AZASO and NUSAS.

In 1987, the United Committee of Concern started a workshop in Wentworth, Durban, to service organisations in coloured areas. Their work also extended to other UDF structures. They produced media for FAWU's 'Boycott Clover' campaign, and 'Don't vote' posters for the campaign against community council elections in black townships.

The Natal UDF set up its own media workshop under conditions of extreme secrecy. The workshop designed its own material and reproduced leaflets and publications from national structures. Enterprising members of local civic structures organised metalworkers in the community to make proper silkscreens for the workshop to use.

Some organisations relied largely on professional photoscreening services. As violence escalated and with almost weekly funerals of activists, commemorative T-shirts and posters were produced using this service. The advantage it offered was photoscreening, essential to the reproduction of photographs of the deceased. Photoscreening technology was available to the Mass Democratic Movement, but was never used widely, largely because it became possible at the same time as desk-top publishing (DTP) replaced silkscreening as a major means of poster production.

The advent of DTP and laser printers made typeset posters accessible to many organisations. The Media Resource Centre at the University of Natal, Durban, the Resource Centre at the Ecumenical Centre in town, the SRCs of UND and UDW and some service organisations became places where poster designs could be produced quickly and easily, with relatively good security. Prior to this, typesetting in Durban was done through a commercial newspaper. Security was always a problem, and many organisations did not have the skills to use the equipment.

While organisations were able to produce more posters this way, disadvantages included the cost of having posters printed instead of silk-screened, the unimaginative designs produced by people new to computers and DTP, and the loss of the organisational benefits of many people together producing media.

The Durban Democratic Association (a UDF affiliate in central Durban) developed an imaginative solution. They printed black and white typeset posters, and then involved members of the organisation in spraypainting other colours onto the posters (by 1989, usually green and yellow).

The problem of bad design has meant that posters and other media are often taken to progressive specialists who produce good designs at lower than commercial rates for organisations. While this produced better media in the late 1980s, it meant skills have been even further removed from grassroots activists.

The Durban Media Trainers' Group, a continuation of the earlier Durban Media Workshop, was formed in 1988 to organise media skills training in Durban and surrounding areas. It has offered training in computer literacy, DTP, silkscreening and poster design. Courses have been run for over 50 community, environmental, welfare, political, church and student organisations. The training emphasised media as an organisational tool, the aim being to empower organisations in the planning, design and production of effective posters using a variety of methods. This has gone some way to addressing the problem of overcentralised skills. Training has been taken to informal settlements and low-tech groups as well as urban-based organisations.

COSATU

CAP, STP and other silkscreen workshops produced posters for trade union struggles in the early 1980s. But the launch of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) in 1985 led to a different kind of demand for posters.

As a national trade union organisation, COSATU needed not a few hundred posters for each local event, but thousands and even tens of thousands of copies, usually in two or three colours (red, yellow and black being COSATU's colours). Offset litho printing was the only real option.

This was not new: some UDF national posters had been commercially printed. But under the Emergency, commercial printers risked serious trouble taking on UDF jobs, including prosecution under the Publications Act. The state appeared initially hesitant to use blatant repressive tactics against trade unions, and COSATU was able to employ commercial printers for very large print-runs.

In May 1987, COSATU acquired its own press in Johannesburg. It printed one colour of its first print-run of 10 000 copies. Before the second colour could be printed, 'persons unknown' bombed COSATU House, destroying the building and completely demolishing the brand-new press.

COSATU resorted once again to printing posters commercially. Of course they still faced problems. Posters always seemed to be needed for today and yesterday. Sympathetic printers produced posters overnight, risking intensified state harassment. After posters were printed; workers sticking them up in the streets often had trouble with police.

Despite differences in scale and production, COSATU posters are part of the same tradition as those from the silkscreen workshops. As the federation grows into the post-apartheid era, posters will continue to play an important part in mobilising and educating their members.

Other poster producers

The Media and Resource Services (MARS) project produced two types of posters between 1983 and 1985.

Staff at this Johannesburg-based community media centre designed A2-size colour posters for major groupings which wanted 'professional' posters and could pay printers to reproduce between 2 000 and 5 000 copies. Once users approved the design and slogans, MARS organised the offset litho printing. Some of these bright and innovative posters included those for the UDF's Signature Campaign and People's Music Festival, and the poster for the first Free Mandela rally held by the Release Mandela Campaign in Sowe-to 1984.

MARS also produced A3-size black and white photocopied posters, to meet the urgent demands of smaller events, such as those held by the various youth congresses. For example, a COSAS branch in Mamelodi would need 50 posters to publicise a meeting. MARS staff would provide on the job training in letraset and design, and assist users with typesetting if desired. Many groups came to MARS to produce pamphlets and newsletters, which they often enlarged to A3 format for wall or office display.

MARS was also a victim of state repression and was forced to close down during the second State of Emergency.

The Graphic Equalizer was a privately-owned design and reprographic studio started with funding from Ravan Press. Faced with a frequently hostile commercial printing industry, many democratic organisations and alternative media turned to the Graphic Equalizer. Throughout the turbulent 1980s, the Equalizer trained groups in the technical skills needed to produce the printed word. For two years, it ran a successful project for school leavers, teaching the skills needed to design and produce posters. The Graphic Equalizer closed down in 1989.

The Other Press Service (TOPS) also engaged in postermaking and skills training. Formed by three journalists in 1987, TOPS' initial work was restricted to the design and production of newsletters and pamphlets, mainly for trade unions and youth congresses.

In late 1987 the organisation acquired its own DTP equipment, and TOPS began to assist in graphic production.

With a full-time staff of three, TOPS now runs a service structure, which typesets, designs and produces media for organisations ranging from rural youth congresses to the head offices of the ANC, SACP and COSATU.They provide an in-house training course for media activists, with special emphasis on DTP, and conduct media training workshops throughout the region. They advise organisations and publications on how to develop their own media strategy.

Choosing images

Like any other work of art, a poster represents a set of aesthetic choices about image, colour, technique and style. These choices are made within a framework defined by existing materials, technical skills, and the ideology of the people and organisations making the choices.In spite of the differences in reproductive processes used by the groups involved, their diverse backgrounds and the large distances between them, such choices and limitations contributed to the similarities of style which characterise the posters of this period.

The first common denominator lies in the imagery, which centres on a relatively small range of political symbols. Some reflect an international visual vocabulary of struggle, such as clenched fists and banners, drawing a link between the issues confronting people in all societies of the world. These images were not only repeated, but also reinterpreted, redrawn and redesigned in ways specific to, and often personally felt by, the people producing them.

Other symbols are unique to South Africa, such as the spear and shield of the ANC and MK, or the photograph of the dying Hector Peterson.

Colour is also symbolic: black, green, and gold for the ANC, red, yellow and black for the UDF and COSATU, and red for struggle, socialism and the SACP.

Apartheid has left South African communities with a limited common vocabulary of images. Colonial suppression of popular culture left little unifying national 'folk' imagery to draw on, such as might be found in the traditional costume of Chile, or the rich connotations of the life-force' represented by the skeleton in Mexico. Traditional symbols that survive have often been trivialised and distorted to fit apartheid's ethnic categories.

Therefore almost every symbol of resistance or political demand had to be established through on-the-ground organisational activity. Each repetition of an image drove it deeper into the cultural awareness of the community. Fists and flags became 'our fists' and 'our flags'. The image of Hector Peterson, the pictures of marching crowds and waving banners became, in some deeper sense, our own.

People increasingly drew images from observing the reality of struggle around them. Time passed and fresh images were incorporated: the tanks and casspirs of the police and army occupation of the townships; the AK-47; the tin shacks of squatter camps; and the clothing, faces and gestures of militant youth and workers. At the end of the decade, portraits of ANC and SACP leaders burst onto the scene, together with the resurgent colours and symbols of the organisations.

Although there is no doubting its effectiveness, such repetition of imagery has at times been a problem. Some media workers feel resistance culture should aim higher than simply popularising key symbols, scenes and personalities. Should postermakers, they ask, confront the issues of cultural creativity — provoking critical thought, challenging precepts, breaking the rules of aesthetic convention — in short, fostering cultural awareness as well as mobilising people politically? These questions must still be answered. Yet, whatever the merits of the aesthetic debate, there can be no doubt that these posters represent, in an important and powerful way, the voices of people previously silent.

A second common feature of most posters of this period is production technique. Many have a hand-made or unskilled appearance, using silk-screen technology in its cheapest and simplest form, hand-drawn images and text, hand-cut or painted stencils, and 'line photography' where photographs were used.

This is partly the result of a lack of resources. But the choice was also motivated by other considerations. The few skilled artists who identified with the people's movement believed they should encourage people to develop their own imagery. Technically skilled workers who supervised the workshops insisted that user groups themselves pick up a squeegie and print the posters they would be using in their communities. These two strands — of political imagery on the one hand, and a community-oriented technology on the other — were the dominant influences on the thousands of posters produced during the 1980s. Other aesthetic influences, however, can also be traced.

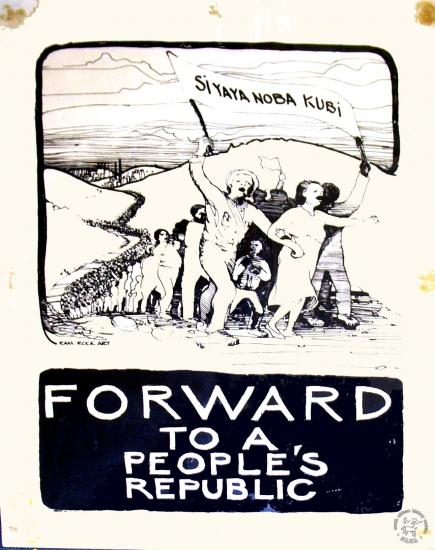

Those few trained artists who brought their skills to the poster workshops did so out of political conviction. Visual imagery of struggle and revolution from other parts of the world often influenced them directly — posters and images from the Russian revolution, from Germany in the 1930s, from France and the US in the 1960s, from Cuba, Nicaragua and Chile, and from the murals and posters of Mozambique in the 1970s. A strong parallel influence came from contemporary black South African artists, drawing on the black consciousness movement of the 1970s, and on the African aesthetic tradition of expressionistic distortion and economy of line and shape.

But these artistic influences should not be over-emphasised. The heart of the process lay in the engagement between those who used the workshops, for whom media production had become a necessary element of political life, and those who ran the workshops, whose central concern lay in democratising visual communications.

In sum, these posters represent a major form of popular visual expression of the period, if not the major form. They are built upon the perceptions, realities and demands of the communities which produced them. People who had been deprived of visual expression turned their hands and creative impulses to making these posters. Many are exciting and beautiful to look at; others show the effects of being a 'first effort' battle with techniques. But above all, they map the spirit of the period — a people's struggle against repression, but also their struggle to catch and reflect a glimpse of a future democratic society.

The next decade and further ...

Two aspects stand out from the uneven development of a poster tradition in South Africa.

Firstly, there is an abundance of enthusiasm, ability and potential for small-scale, grassroots media production. That much is evident in the pages of this book. Secondly, the tools for this kind of communication should be made available to the widest possible audience.

Over the last few years, media production within the progressive movement has tended to become more centralised. Organisations depend on computer-generated type and design for the sake of speed, convenience, and 'professional' appearance. Posters have tended to become uniform, mechanically functional in appearance, and all too often with lines of Helvetica in varying sizes.

Most posters are now printed commercially. This makes sense for the central structures of organisations like COSATU and the ANC, which have to produce large numbers of posters quickly. But smaller organisations cannot afford commercial production, and have often stopped using posters. High technology production also concentrates skills in just a few hands.

Silkscreening and other simple, non-mechanised forms of design and production make it possible to involve even the most technically inexperienced in the most far-flung communities in writing, drawing, designing and producing their, own media. The low cost of the equipment and of the printing method also bring printing within economic reach for most communities.

CAP and STP were the 'barefoot' element in the development of the media as the voice of people's power over the past decade. This element must continue in a future South Africa.

The democratic movement faces a daunting number of media challenges over the next period. The greatest is finding a place in the mainstream mass media. If mainstream media is to speak to, and for, the people of South Africa, it must be informed and stimulated by its living counterpart at grassroots level. This process cannot be taken for granted, nor is it a romantic vision. There must be serious thought and necessary resources to ensure that a popular voice continues to be heard.

We look forward to moving away from the confrontation and destruction which marked the years of struggle against apartheid. The process of building a just and democratic South Africa demands that all the people of our diverse communities participate in reconstruction. Posters can play a key role in that process: educating and informing people, promoting literacy programmes, health and safety campaigns, and recruiting support for other social projects.

At the same time, posters can also provide a vehicle for activists and grassroots members to contribute their own ideas to this reconstruction. Posters can carry not only the word of the state to the people, but the voice of the people themselves.

Over the decade of the 1980s, posters in South Africa played a crucial role in expressing the demands and beliefs of communities suffering under apartheid. Now, in the 1990s, we should use posters in the key task of building a national consciousness among all South Africans. In so doing, South Africa could take the art and practise of postermaking to new heights.