[For more information on individual posters, click or hover over images]

Independent trade unions have long been a part of the South African liberation movement. The first black trade union emerged as long ago as 1919, when the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed in Cape Town. In succeeding decades it was followed by many others, including the Council of Non-European Trade Unions (CNETU). These unions achieved some gains for their members, but none managed to gain the official recognition the state reserved for white unions.

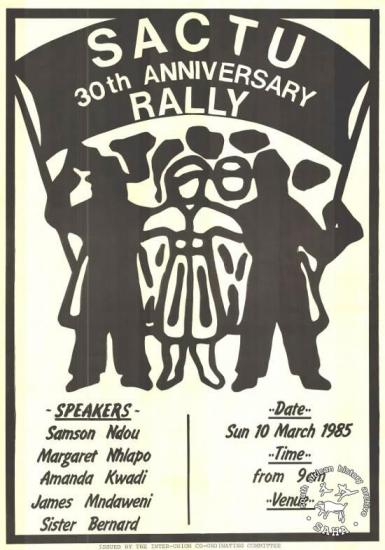

After the National Party came to power in 1948, black unions found many of their leaders banned from trade union work under the Suppression of Communism Act. Determined to resist, the union movement regrouped and in 1955 formed the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU). In the face of a common onslaught from the government, SACTU joined forces with the African National Congress (ANC) and others to form the Congress Alliance. It reflected their belief that workers' rights could never be adequately defended as long as apartheid existed.

SACTU eventually succumbed to state repression and in the early 1960s, following the Sharpeville massacre and the banning of the ANC. was driven underground. The following ten years were a dark decade for black trade unions.

In the early 1970s, workers began reorganising in Durban. In 1973, mass strikes broke out in support of demands for wage increases. This marked the rebirth of the independent trade union movement.

Unions emerged in the major urban centres of Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town, and despite intense harassment, managed to survive and grow. The union movement's democratic structures proved resistant to repression, and by 1979 both employers and the state agreed that black unions should be legally recognised. The authorities believed limited recognition would result in more effective control of union activities.

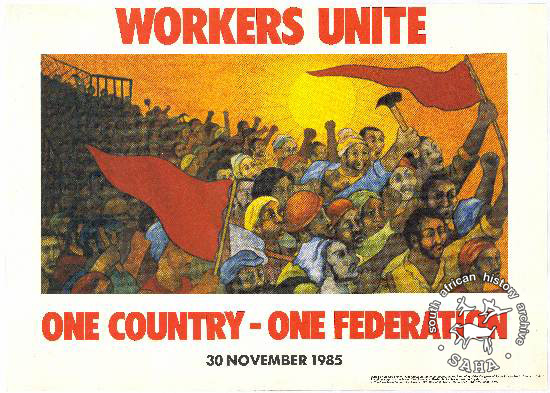

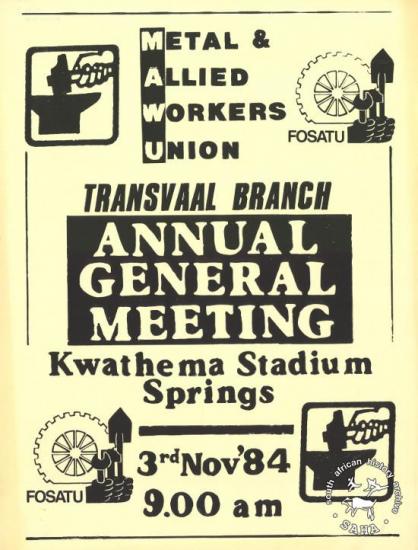

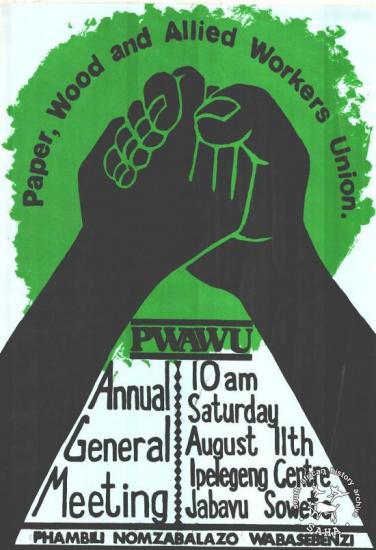

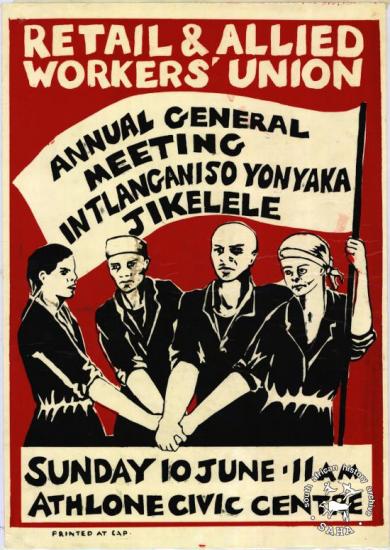

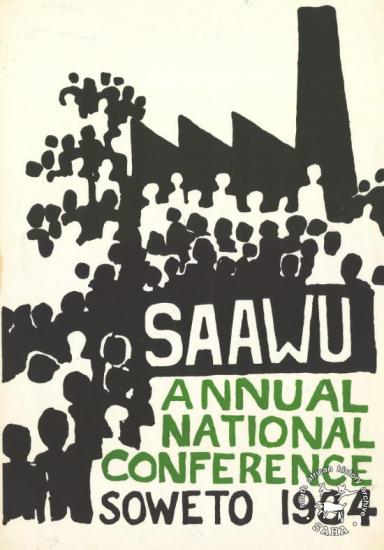

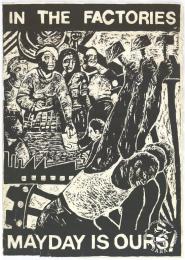

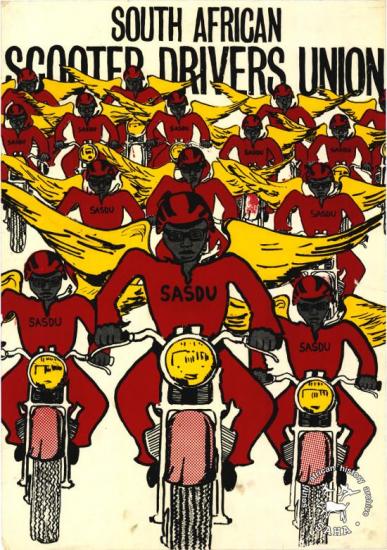

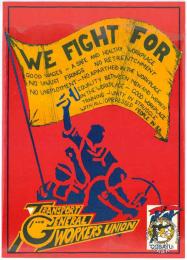

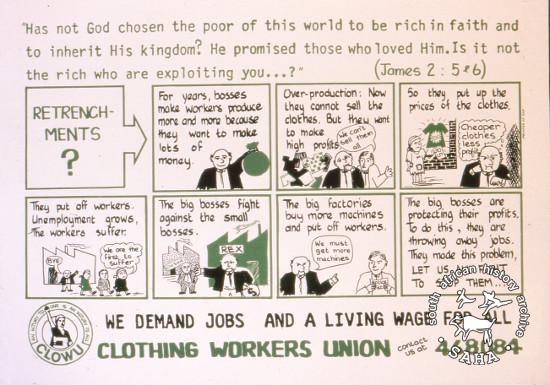

However, the independent unions refused government regulation and continued to organise against low wages and racism, both at work and in the wider society. The Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU), the South African Allied Workers Union (SAAWU), the Western Province General Workers Union (WPGWU), and the Food and Canning Workers Union (FCWU) were among the most prominent of the unions engaged in bitter battles to organise and expand the frontiers of unionisation.

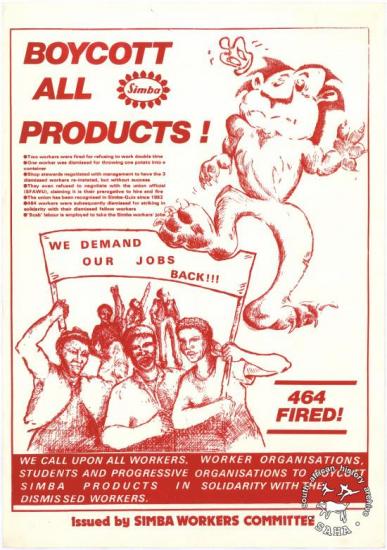

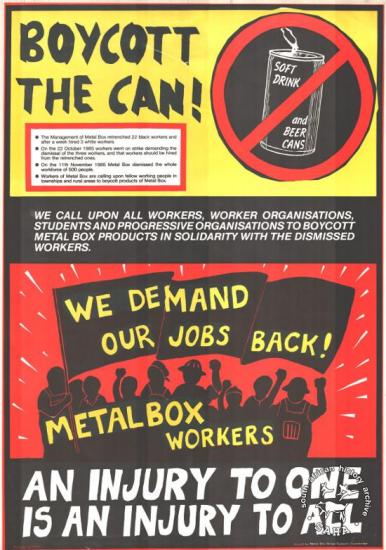

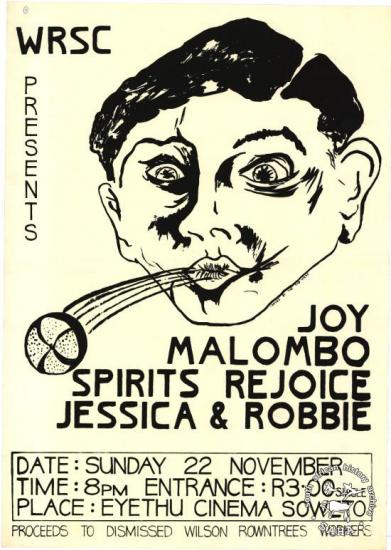

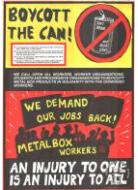

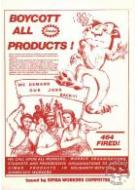

New tactics emerged, including calling on community organisations to support striking workers by boycotting company products. The FCWU used this tactic during the Fattis and Monis strike, as did SAAWU during the Wilson-Rowntree dispute. The early 1980s also saw the 1950s tactic of work stayaways revived.

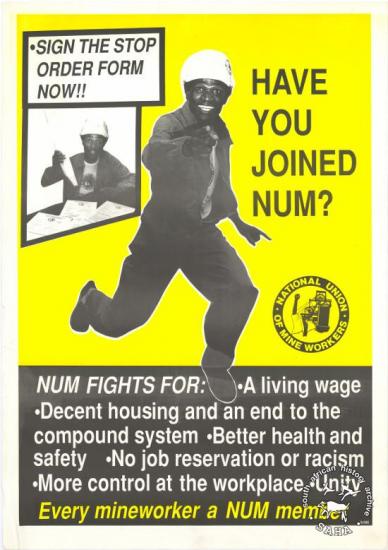

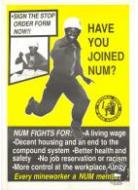

The emergent unions recognised the need to unite into one trade union federation. But a variety of differences, both organisational and political, made this a lengthy process. During four long years of unity talks, the unions grew rapidly, and new unions, such as the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), were established.

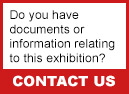

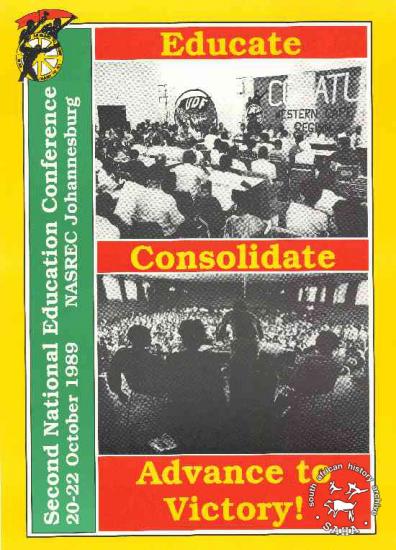

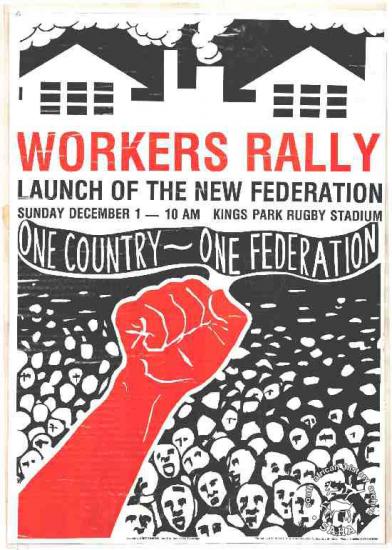

The political climate within the country also changed. Growing opposition to apartheid resulted in widespread resistance in the face of an intransigent government. This grassroots movement was strengthened by the formation, in 1983, of the United Democratic Front (UDF), which brought together a wide range of antiapartheid organisations, including a number of the emergent unions. By 1985, most of these emergent trade unions announced themselves ready to unite under the banner of 'One Country, One Federation'.

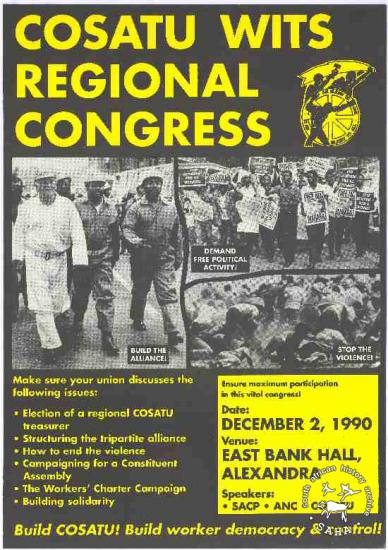

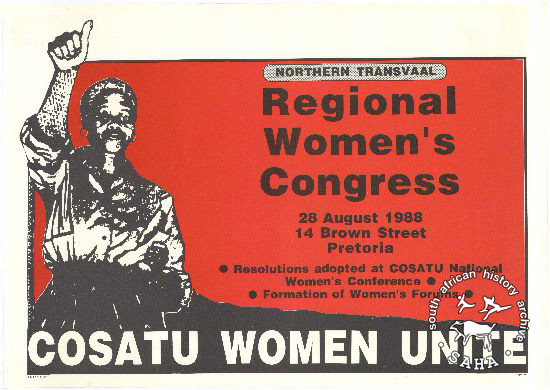

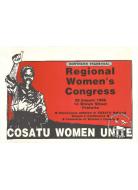

On 1 December 1985 the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) was launched in Durban. It brought together 33 unions representing some 450 000 organised workers, making it the largest trade union federation ever formed in South Africa. Elijah Barayi, a mine employee, was elected president, and Jay Naidoo, previously general secretary of the Sweet, Food and Allied Workers Union (SFAWU) was elected general secretary. COSATU openly proclaimed its determination to be politically active: it would fight for a non-racial, democratic South Africa.

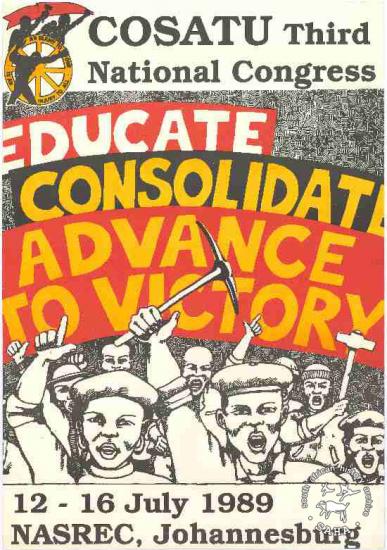

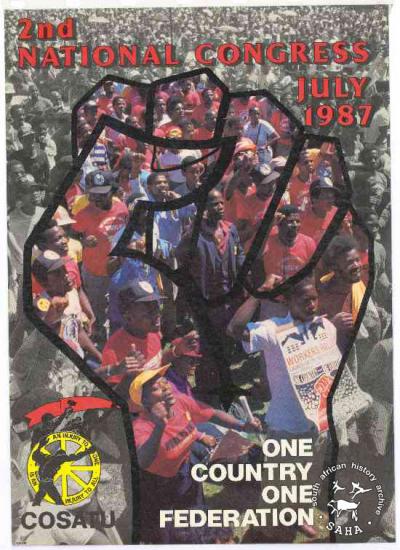

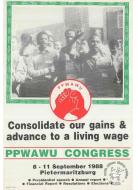

Among the policies adopted by COSATU was that of creating one strong union in every industry, by uniting the various smaller unions organising in each sector of the economy. 'One Industry, One Union' became its guiding slogan. In its first five years, COSATU had combined the original 33 affiliates into 13 much larger, stronger, industrial unions.

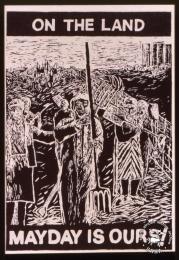

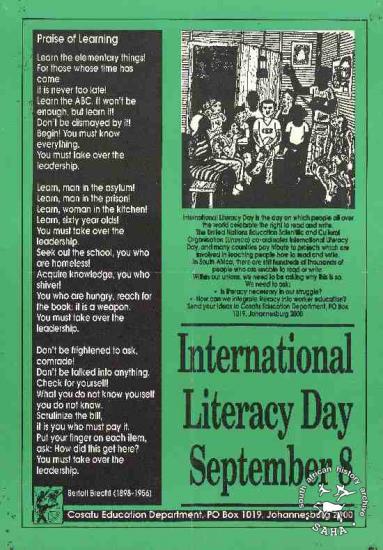

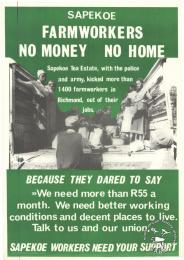

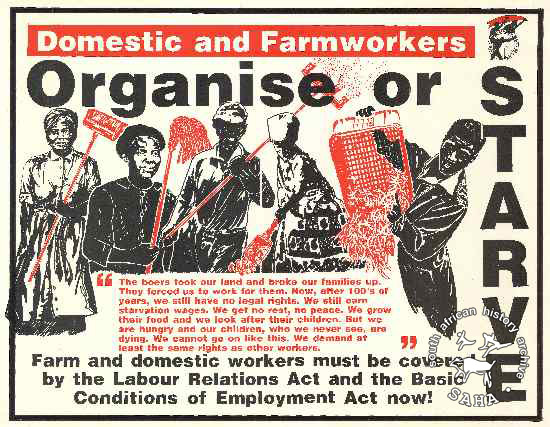

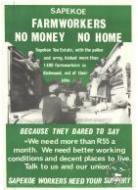

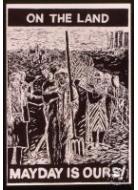

COSATU's formation also saw a dramatic growth in the number of unionised workers. By mid-1988, COSATU represented some 700 000 workers. Part of this growth stemmed from its policy of organising in sectors where unions were not yet legally recognised. This included organising workers on the farms, in domestic service and, particularly, in the public sector. Membership grew as railway workers, postal workers and others flocked to join the unions. Recognition of these unions was only achieved after lengthy and often bloody battles against a well-armed state. The railway strike of early 1987 brought a measure of recognition to COSATU's railway union, but not before police had killed a number of strikers.

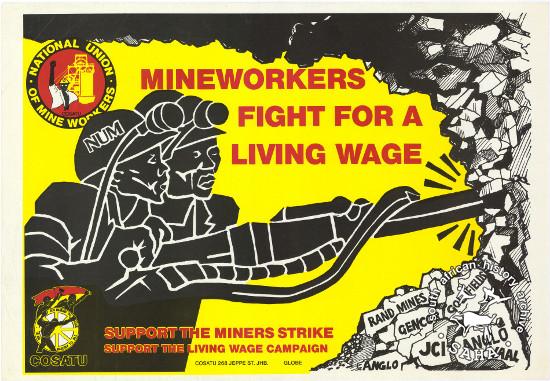

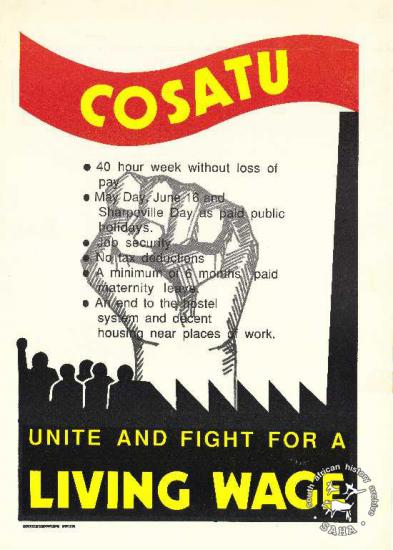

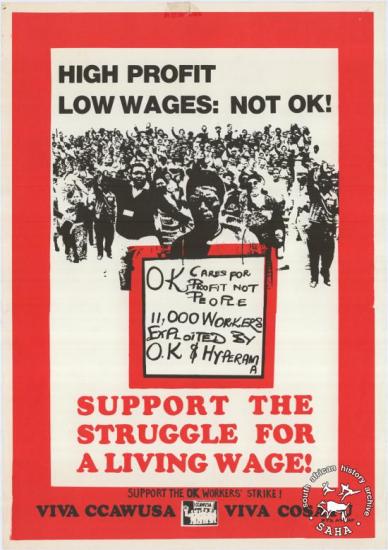

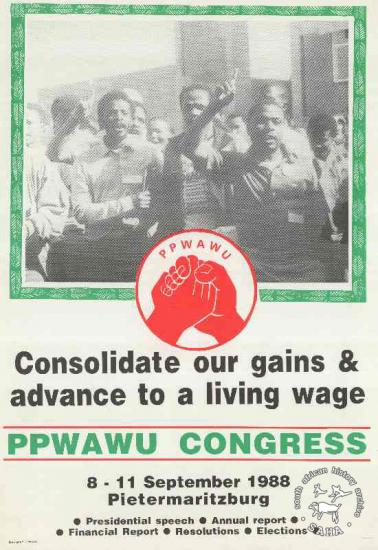

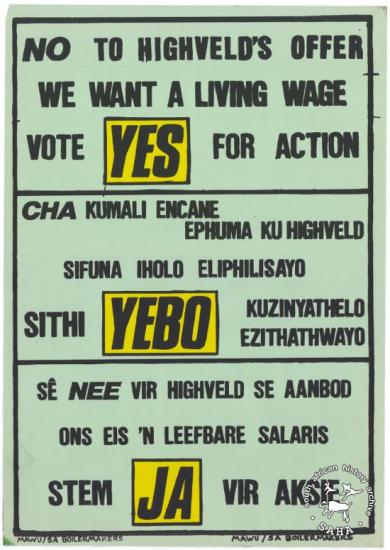

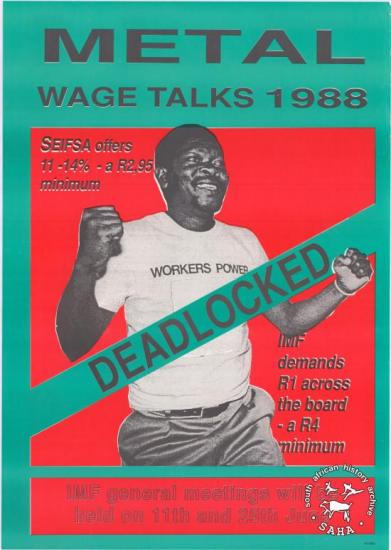

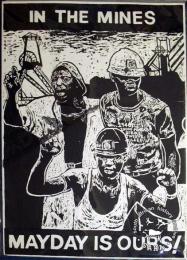

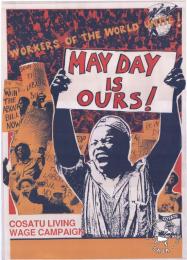

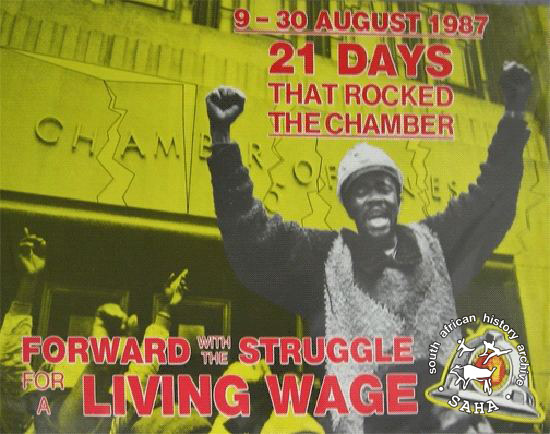

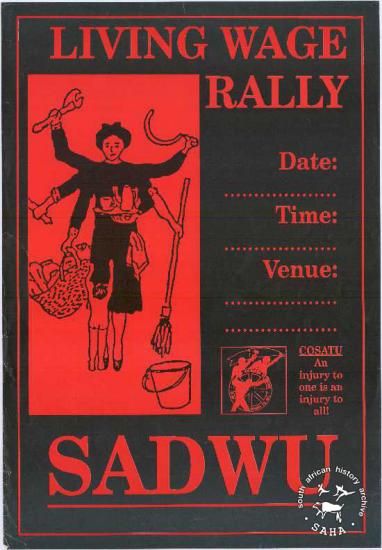

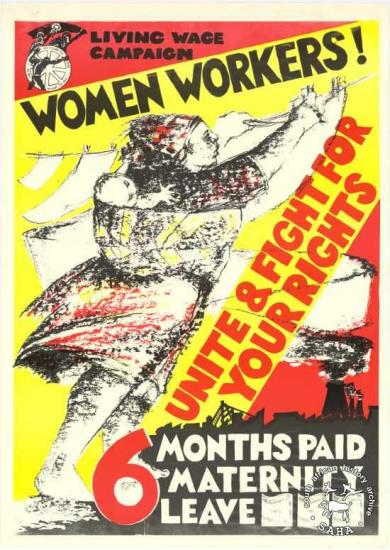

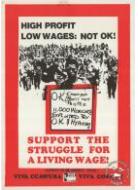

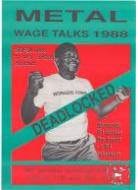

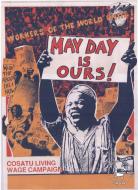

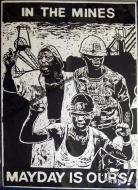

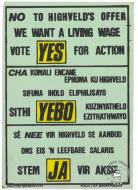

Another COSATU battlefront has been its Living Wage Campaign, with union members involved in major wage strikes in all industries. The most dramatic of these occurred on the mines during mid-1987 when some 350 000 miners downed tools for 21 days. This, the biggest strike in the country's history, hit hard at the core of the economy, the gold mining industry.

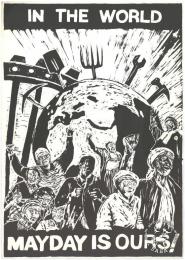

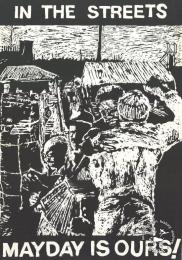

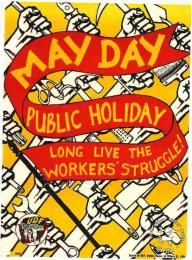

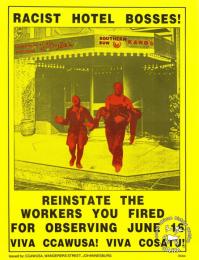

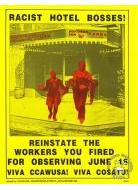

The Living Wage Campgain focused not only on wage increases, but also on achieving other changes — public holidays, for example, have been a major battleground. COSATU's members have fought and succeeded in having internationally-celebrated May Day recognised as a public holiday in South Africa. This was achieved only after the federation organised massive work stayaways on 1 May for a number of years. COSATU has also achieved a large measure of success in getting 16 June (the anniversary of the Soweto uprising), and 21 March (the anniversary of the Sharpeville massacre) recognised as public holidays — in fact if not in law.

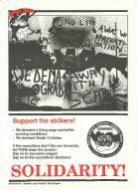

None of these achievements were easily won. COSATU has existed under an almost continuous State of Emergency which involved intense repression of trade unionists, together with activists in youth, community, religious and political organisations.

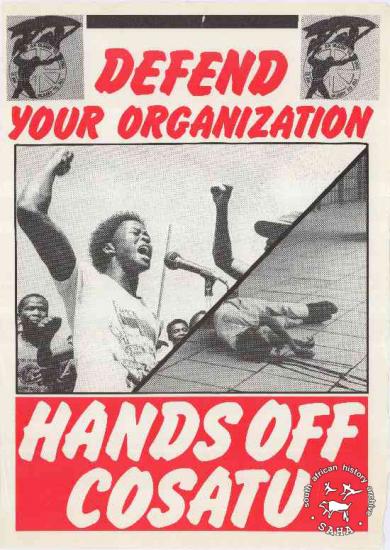

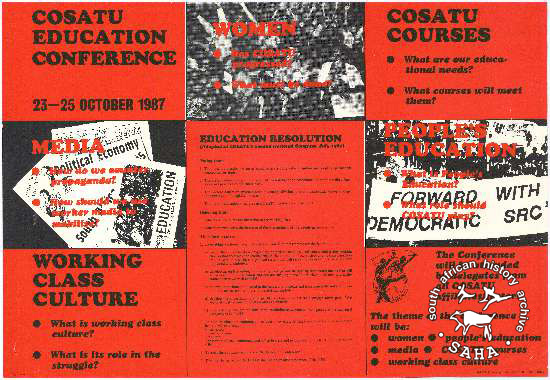

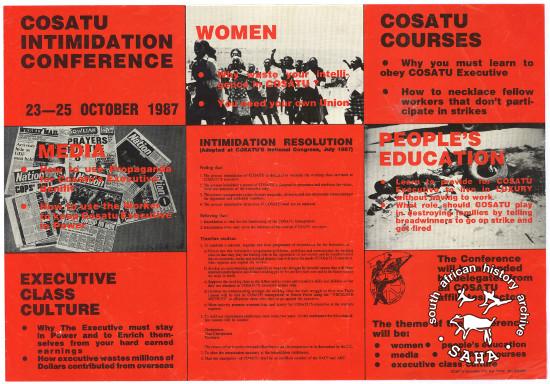

A propaganda war aimed at undermining COSATU involved the widespread distribution of dirty tricks pamphlets and posters. And repression did not stop with words: thousands of unionists found themselves detained and held without charge, often for lengthy periods. Others have been assassinated, the victims of secret death squads. Union offices have been raided by police, vandalised, bombed, and burned to the ground. The most vicious attack occurred in May 1987 when COSATU's headquarters in Johannesburg were destroyed in a massive explosion. The police have still failed to apprehend the perpetrators of any of these attacks.

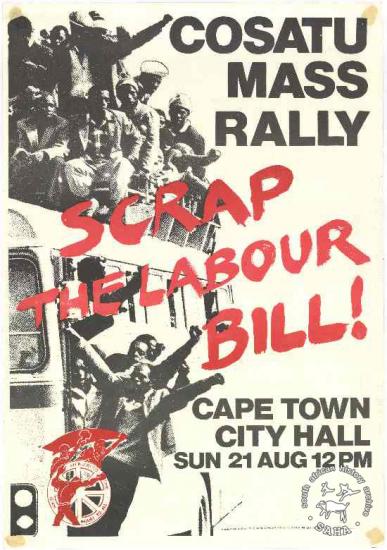

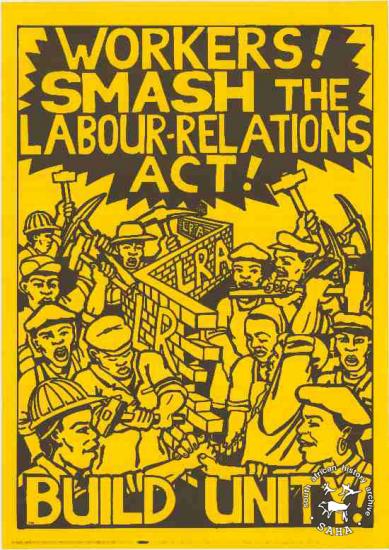

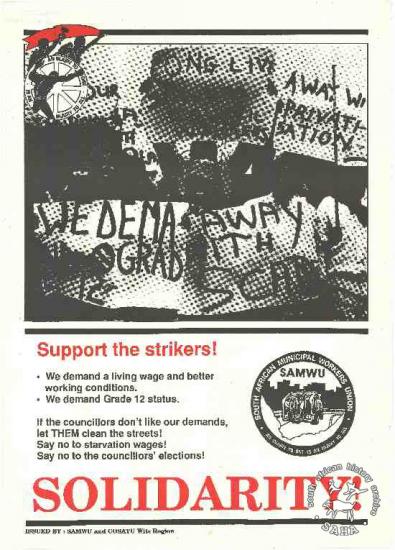

Repression failed to intimidate either COSATU or its affiliated unions. As a result, more systematic attacks were launched against it in 1988. In February, the government restricted COSATU from any participation in politics, at the same time banning the UDF. Breach of these regulations was punishable by heavy jail sentences and fines. In addition the government, at the urging of employers, introduced a new labour law. The Labour Relations Amendment Act aimed at reversing many reforms introduced in 1979. Both the restrictions and the new labour law fostered greater unity among COSATU affiliates. There was widespread defiance of the restrictions on its political activities — the new labour law, although promulgated, was rendered largely a dead letter. Two major national stayaways were central to achieving this. One stayaway lasted three days, and in both, millions rallied to COSATU's domesdefence. These stayaways were conducted jointly with many non-COSATU unions, in particular those affiliated to the National Council of Trade Unions (NACTU).

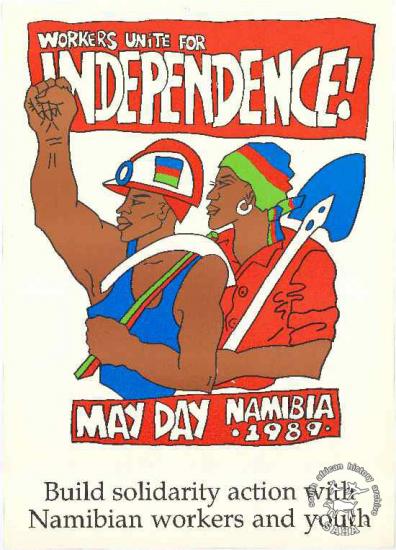

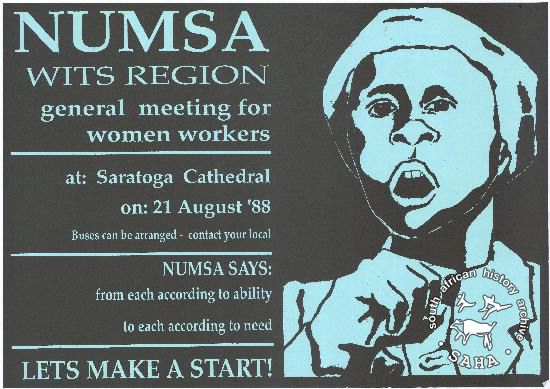

Not all COSATU's activities have been so spectacular. Like trade unions worldwide, it has involved itself in the normal range of bread-and-butter activities. It has attempted, with a large measure of success, to draw unions outside COSATU into its ranks. It has tried to harness militant rural workers into disciplined unions. It has developed links internationally, and played an important part in assisting the development of independent unions in Namibia.

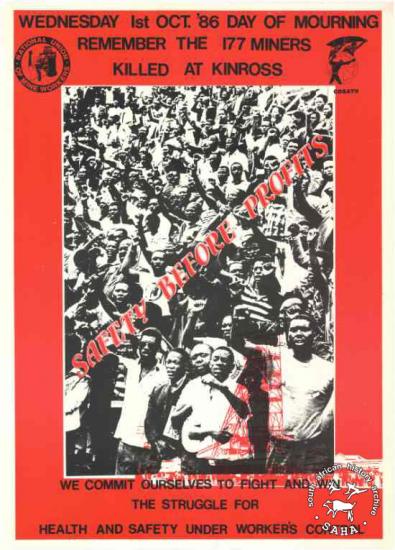

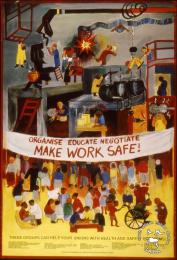

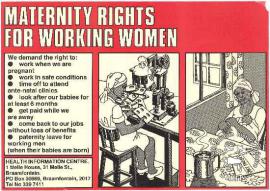

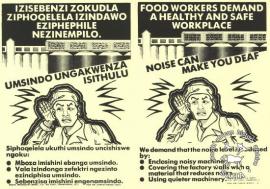

COSATU unions have taken up health and safety issues. The miners' union, NUM. is particularly active in this regard. The dangers facing mineworkers were demonstrated by an horrific accident during September 1986, when 177 workers died at Kinross gold mine.

Since its inception, COSATU has been politically active. In 1987 it adopted the Freedom Charter, thereby aligning itself with the non-racial, democratic perspective of the ANC. With the unbanning of political organisations in February 1990, these links strengthened.

COSATU has stressed both its determination to remain politically active in the search for democracy, as well as its desire to remain independent. This has involved retaining its strongly separate identity, but entering into a strategic alliance with both the ANC and SACP.

Today COSATU is widely recognised, by friend and foe alike, as one of the pillars of the liberation movement. It now represents over a million workers, with organisation expanding daily. Its existence is a challenge to a post-apartheid South Africa. The majority of South Africans want not only political rights — they also demand social and economic justice.

Link to SAHA Workers Commemoration Virtual Exhibition