Because black consciousness had inspired many Soweto students to take decisive action against their own oppression, the apartheid state focused its attention of Steve Biko and the BCM.

Initially, the government did not see black consciousness as a real threat. Rather, the state believed that BC’s philosophy of black people working on their own fitted well with its own philosophy of separateness as seen in its policy of apartheid and the creation of the homelands. However, as SASO membership swelled and other BC organisations grew in support, the state began to crack down on Biko and other leading members of the BCM.

In 1973, eight black consciousness leaders, including Biko, were banned. This meant that for five years they were restricted to the area in which they lived, and could not speak to or meet with more than one person at a time. This prevented them from attending political meetings and rallies. The government gave no reasons for the bannings but it was clear that the government hoped to crush the black consciousness movement. By the end of 1973, more leaders had been banned, and some placed under house arrest.

In 1975, the SASO Nine were brought to trial for allegedly conspiring to bring about revolutionary change. Biko’s banning orders were relaxed so that he could testify on their behalf. This drew the interest of the media worldwide. The SASO Nine were found guilty under the Terrorism Act.

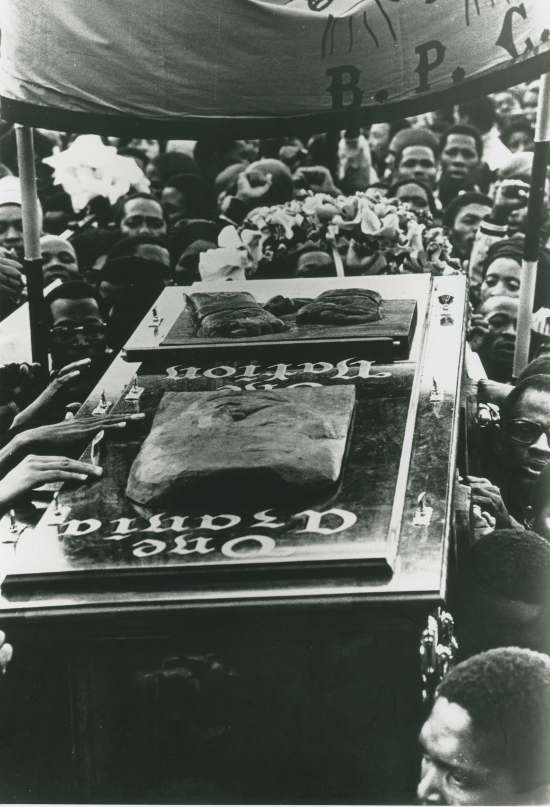

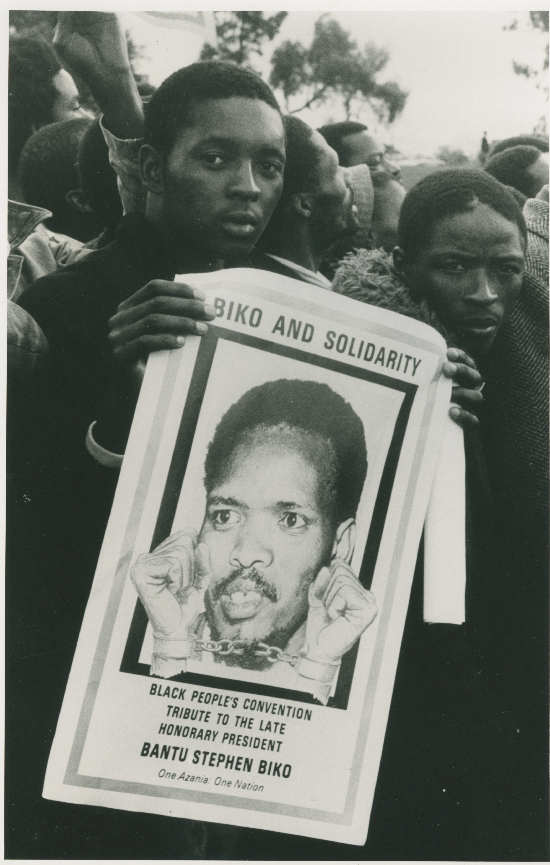

After the Soweto Uprising, Black Consciousness was systematically targeted. Biko often ignored his banning orders in order to address crowds and to continue his work in the movement. On 17 August 1977, he left Port Elizabeth and travelled with Peter Jones to the Cape to attend a meeting. They were stopped at a roadblock and were detained. On 12 September 1977, Biko died of injuries sustained during interrogation. His death stunned and shocked the world. But not Jimmy Kruger, the Minister of Justice, who stated that Biko’s death ‘left him cold’.

An official inquest into Biko’s death, despite evidence to the contrary, found in favour of the police, stating that his death could not have been brought about “by any act or omission involving an offence by any person.” Biko was the twentieth detainee to die in custody. South Africa had lost one of its most influential young men.

It was only at the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC) that the truth of Biko’s death was revealed. Four security policemen admitted to the killing of Biko during interrogation. The commanding officer, Gideon Nieuwoudt was denied amnesty on the grounds that he did not prove that his crime was politically motivated.

Exibitions in the classroom

Reading the past

SOURCE:

“I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko. His death leaves me cold”

- Minister of Justice, Jimmy Kruger in The Cape Times, 15 September 1977.

Read the quotations made by the Minister of Justice, Jimmy Kruger, on the subject of Steve Biko’s death.

- What is Kruger’s tone in both the quotations?

- What does his tone suggest about the man and the nature of the apartheid government?

- If you could respond to these comments in person to Jimmy Kruger, what would you say to him?

Pausing for thought

Think about Steve Biko

If Steve Biko was alive today, what do you think he would think about the last twenty years of democracy? Discuss this in your groups.