After the October crackdown of 1977, youth and student organisations began to revive slowly. This included the Soweto Students’ Representative Council (SSRC), which had been responsible for the coordination of many of the events of June 1976. This new generation of young activists were younger and less experienced than the students of 76.

After the October crackdown of 1977, youth and student organisations began to revive slowly. This included the Soweto Students’ Representative Council (SSRC), which had been responsible for the coordination of many of the events of June 1976. This new generation of young activists were younger and less experienced than the students of 76.

This group of student activists centred much of their protests on the ongoing issue of Bantu Education, as they called on the youth to boycott school. Another target of youth anger was harnessed against black collaborators, who worked within the apartheid system as police or as officials in local councils.

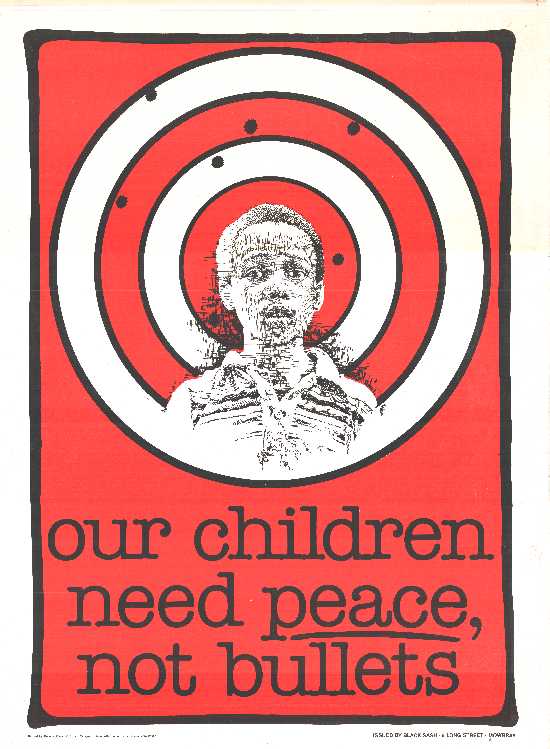

As the school boycotts continued into the 1980s, the police and the army did much to stir up the anger of the youth. They terrorised students by throwing teargas into schoolrooms, beating them, and firing buckshot and rubber bullets at them. A teacher in Soweto commented:

“Some of the kids are scared to death, others are angry."

Before the mid-1980s, Baragwaneth Hospital reported that the majority of violence-related injuries were on patients between the ages of 35 to 40. During the 1986 state of emergency, the majority of injured patients were children from 14 to 18 years. It was clear that the security forces were targeting children.

Before the mid-1980s, Baragwaneth Hospital reported that the majority of violence-related injuries were on patients between the ages of 35 to 40. During the 1986 state of emergency, the majority of injured patients were children from 14 to 18 years. It was clear that the security forces were targeting children.

Increasingly, in the 1980s, more and more student leaders, activists and children of a very young age were detained, without access to lawyers or their parents. Once in detention, they were extremely vulnerable and had little protection against police brutality. By 1986 it was estimated that about eight thousand detainees were below the age of eighteen, many of them in their early teens, but some as young as seven to ten years old. Children were subjected to the same conditions in detention as adults. They were often tortured during interrogation and were held for long periods of time.

A group of concerned parents of detainees formed the Detainees Parent Support Committee (DPSC). This was a multi-racial group of parents who tried to gain support for their children in detention and worked to expose the abuses of the security forces. The DPSC reported a pattern of abuses against young people. Soldiers would pick children off the streets and hold them for several hours or take them into the veld. Here, children were brutalised. They were beaten with fists, rifle butts and often were subjected to electric shock treatments. Some had petrol poured over them and then held near open flames.

The brutalisation of children in prisons and on the streets of the townships is a mark of shame against the apartheid regime that should be remembered in time to come.

Exhibitions in the classroom

Working as a historian

SOURCE: “Rights of Children Under International Law Kader Asmal, September 1987.

Look at the statistics of police violence against children from 1984 to 1986.

- How many children died through police action during this period?

- How many children were detained during this period?

- What do all the statistics reveal about police attitudes towards children?

- Why are these statistics not considered to be accurate?

- If they are not accurate, are they still useful? Explain your answer.

Learning more

Learn more about death in detention on SAHA’s DVD: Between Life and Death – stories from John Vorster Square or online on SAHA’s virtual exhibition “Detention without trial in John Vorster Square on the Google Cultural Institute website.