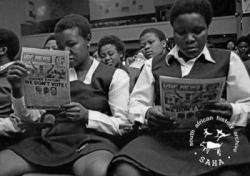

At the height of resistance in the mid-1980s secondary and high school students were at the forefront of the struggle, initially, against the education authorities, and finally, the apartheid regime in general. In the first three years of its foundation, Cosas did not focus on student-based issues; instead mainly became involved in national politics. This resulted in the detention of almost the entire leadership of Cosas. Its first president Ephraim Mogale was subsequently charged with furthering the aims of the ANC and the South African Communist Party (SACP).73 From 1983, as school boycotts became increasingly common, Cosas re-orientated its strategy towards education-based issues.

At the height of resistance in the mid-1980s secondary and high school students were at the forefront of the struggle, initially, against the education authorities, and finally, the apartheid regime in general. In the first three years of its foundation, Cosas did not focus on student-based issues; instead mainly became involved in national politics. This resulted in the detention of almost the entire leadership of Cosas. Its first president Ephraim Mogale was subsequently charged with furthering the aims of the ANC and the South African Communist Party (SACP).73 From 1983, as school boycotts became increasingly common, Cosas re-orientated its strategy towards education-based issues.

In 1984 Cosas tabled five key demands that were later taken up by secondary and high school students in different areas. It demanded the Student Representative Councils (SRCs) replace the prefect system, the removal of the age limit rule, an end to corporal punishment, that teachers stop sexually harassing female students, and that the police and South African Defence Force (SADF) be withdrawn from schools and townships. It was against this background that high and secondary schools students began to mobilize in different townships across the country.

Students at Tembisa formed branches of Cosas to take up some of the key demands tabled by Cosas national. This was after they had been influenced and guided by Michael Figo Madlala and Brian Mazibuko, who had been incarcerated on Robben Island for five years since 1977.

However, it was the branch of Cosas at Jiyane Secondary School which influenced student politics in the township.

Greg Thulare and Debra Marakalala remember this branch's role as follows:

"People would meet then and make sure that from those plenary sessions we go out and implemented the [resolutions]. Because of the energy and accessibility of youth ... Jiyane Secondary School was ideal because of the situation there. The level of discipline in Jiyane and the other general problems which were there: corporal punishment.

"It was a perfect breeding ground to start to mobilize students, get them into formations, identify comrades ... Hence our association with Thabiso [Radebe] and the others. One could communicate with them, and bring them into this formation. You see, one's life was influenced a great deal to say if you are not in the student movement you have to be in other formations - one or another. And that took a turn to say wherever you go you had to mobilize students. In the end we formed Cosas. And Cosas in Jiyane influenced the formation of Cosas in the other two high schools, Boitumelong and Tembisa High. Because of concentration and the level of mobilization at Jiyane we were able to move things faster and speedily."- Rosina Marakalala1- Greg Thulare -1-

Mncedisi Prince Sibanyoni concurs:

"Dr. Semetse, Kabelo and many others like Mthofu Khumalo were the people who were pushing the struggle. We attended at Tembisa High School, even though they were ahead of us by a grade. I went to a meeting near Oakmoor Station at Xuweni. There is a hall there where they conducted their meetings. I got there and guys were appointed to various leadership positions from different schools. Then came elections for the Cosas Tembisa High branch, I got myself a position on the top five as an organiser. The first thing we wanted in our school was the introduction of the student representative council and the end of corporal punishment."

When both the schools' management and the Department of Education (DET) refused to give in to the demands by Cosas, students in Tembisa called for a class boycott. The Sowetan reported that in July 1984 about 7 000 pupils (students) boycotted classes because of the refusal by school's authorities, among other things, to introduce SRCs to replace the prefect system.

The boycott continued indefinitely and in the following year the DET suspended five schools in Tembisa. These were Jiyane, Thuto-Ke-Matla Junior Secondary, Boitumelong Senior Secondary, Tembisa High and Masisebenze Secondary.80 In addition, the state responded with force, detaining student leaders.

Greg Thulare, a student at Jiyane and an organizer for Cosas in Tembisa, was one of those detained. His bail application was denied after a security policeman argued at the Kempton Park magistrate's court that Greg planned to leave the country if he was granted bail.81 In April 1985 Greg Thulare's home was petrol bombed. This was clearly a way of intimidating his family, probably to force him to relinquish his participation in student politics. On 25 August 1985, the government banned COSAS.

Greg Thulare, a student at Jiyane and an organizer for Cosas in Tembisa, was one of those detained. His bail application was denied after a security policeman argued at the Kempton Park magistrate's court that Greg planned to leave the country if he was granted bail.81 In April 1985 Greg Thulare's home was petrol bombed. This was clearly a way of intimidating his family, probably to force him to relinquish his participation in student politics. On 25 August 1985, the government banned COSAS.

At this stage youth congresses had been formed in townships across the country to cater for young workers and non-school going young people in the townships. For Charles Carter, the decision to form youth congresses was, inter alia, "made [by Cosas] in response to allegations by the Minister of Law and Order, Louis le Grange, that non-students were directing the activities of the school-based organization".82 In Tembisa, young people formed Tembisa Youth Congress (Teyco), a predecessor of Moya Youth Movement. Members of Teyco were plagued by similar state repression. Teyco's President Sam Semetse, Philemon Nzimande, Teyco's secretary general, and Debra Marakalla and Godfrey Qwabe were detained. Constant police harassment and the possibility of detention forced some of the student and youth activists to flee the country into exile. Their escape was in most cases facilitated by the underground operatives, one of whom was Sello Serote.

Recalling how he helped Leeuw and Elsie to flee into exile, Serote had this to say:

"I took Leeuw out of the country after they had attacked their targets. After they had parted ways with Gezani - Gezani had crossed into Botswana - Leeuw came to me with his girlfriend, Elsie. I asked him if he had informed her about our plan and he affirmed. I transported them. When she saw the fence that they were supposed to cross into Botswana, she clung on to me, begging me to return home with her. I said ‘Are you crazy? You're not going back home. You have to jump this fence'. They finally jumped the fence at Makgobistad, near Mafikeng."

NEXT: Underground operatives in the 1980s

1. interview with Greg Thulare and Debra Marakalala by Tshepo Moloi, for SADET Oral History Project, Midrand, 19 November 2004.