The Black Consciousness Movement and student uprisings, 1970s

The Black Consciousness Movement and student uprisings, 1970s

Towards the end of the 1960s many black students at tertiary level were disenchanted with the predominantly-white led National Union of South African Students' (NUSAS) leadership - one of the few remaining vehicles for multi-racial political activity".21 They felt that the latter, and the white members of NUSAS in general, paid lip service to the total destruction of the Apartheid government; but they, nevertheless, were content with the status quo because they benefited from it. The situation reached a boiling point in 1967 at the NUSAS conference held at Rhodes University, Grahamstown. The NUSAS' conference organizers failed to secure accommodation for their black members in the same venue as the white and Indian members of NUSAS at the University. Instead, the black members of NUSAS were accommodated in a church outside the whites' only designated area.

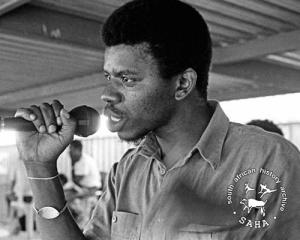

Although it was not NUSAS's fault that the University followed the government's discriminatory policy to the letter, Biko and his peers felt betrayed by NUSAS leadership. It was against this background that SASO was formed in 1969, and formally launched in 1970 at the University of the North (or Turfloop University), where Biko was elected its first president. The Biko's SASO popularized the Black Consciousness (BC) philosophy. In December 1971 Biko described the BC philosophy as follows "... Black Consciousness in essence ... seeks to demonstrate the lie that black is an aberration from the ‘normal' which is white".23 The objective of the BC philosophy was clearly to instill pride in black people. It was for this reason that SASO developed the slogan ‘I'm black and I'm proud'. The BC philosophy, however, did not remain at the tertiary institutions but spread to the townships. In 1972 the Black People's Convention (BPC) was established to cater for the township-based adherents of the BC philosophy who were not at tertiary institutions.

Mongezi Maphuthi, who had recently moved to Tembisa, remembers that in the early 1970s Black Consciousness (BC) ideas were already being disseminated in the township. According to him:

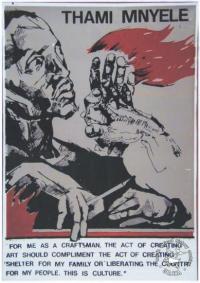

"People like Mthuli Shezi, Thami Mnyele, Mxolosi Moyo, and James Moleya ... were exponents of the the BC ideas. Shezi even wrote a play called Ashanti. He was killed at the Germiston train station by boers who pushed him in front of a moving train."

- Mongezi Maphuthi 1

Similarly, Greg Malebo recalls:

"We had Ralph Mothiba who was in the Black People's Convention. He really played a role in shaping our political thinking in that during the History lesson in particular we'd talk about Kwame Nkrumah, African Unity, Patrice Lumumba. He'd talk about all those things."

However, it was Thamsanqa ‘Thami' Harry Mnyele more than his colleagues who seemed to have made a lasting impact on many young people in Tembisa in the early 1970s. Mnyele was born in Alexandra Township in 1948. While living in Alexandra, he joined Molefe Pheto's Mehloti Black Theatre. This theatre group included personalities such as Wally Serote and Michael "Baba" Jordan. Jordan claims that the group's main objective was to conscientise black people to fight for their rights. It underscored this goal by refusing to perform in white suburbs and preferred to perform in townships.

Mnyele's political understanding developed during this stage. Jaki Seroke, who lived in Alexandra with Mnyele, remembers that Mnyele and some of his contemporaries like Wally Serote used to engage in serious discussions about the position of a black person in the racist South Africa.

"Thami Mnyele, when he lived in Alexandra Township, liked jazz and used to discuss the plight of the black man. Mnyele and others like Wally Serote used to talk about this issue and sometimes even make a joke about it, but in a way that they were articulating their views.

"I mean, they were educated people compared to some of the workers who were employed in the factories. They had matric; some even had degrees. I know one of the guys worked in Germiston at the Pass Office as a clerk. I think he had a B.A. degree in Public Administration. But they were frustrated. And they would say, in spite of their education, they still didn't enjoy a good life, because they couldn't get a house. I can still remember that they would laugh at this guy who worked at the Pass Office and say that even with his degree he was pushed from pillar to post by Afrikaners who were not so well educated."- Jaki Seroke 2

Mnyele was also an artistic painter. He exhibited some of his work in different townships across the Rand. When the Mnyele family relocated to Tembisa, Thami became instrumental in mobilizing young people and conscientizing them. Timothy and Matilda Mabena were some of the young people recruited by Thami and his fellow BC adherents.

Matilda Mabena explains how they were drawn closer to Thami's political network:

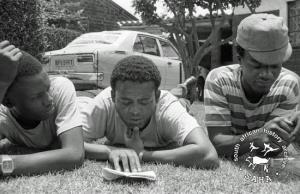

"There was a group of people who were from Alexandra who were staying in Difateng section. They approached a few students and informed them that they wanted to form a social club. This is where we were taught how to play chess. We would read and practice drama. They also taught us to play tennis. I can still remember Thami Mnyele used to play tennis. They then introduced us to jazz and artists like Abdullah Ibrahim, Duke Ellington, Hugh Masekela, Herbie Hancock. Some of them had already completed their matric level and others were teachers. We realised later that some of them were involved in Black Consciousness Movement. Thami Mnyele, James Moleya, Ralph Mothiba, Obed Raphalla, Mazizi Mbuqe, and Mike Mthembu were some of the people who opened our eyes. Brian Mazibuko was also recruited into politics during this period. And he developed quickly. In 1976 he was the leader during the student uprisings."

Timothy Mabena, adds:

"We would meet in different houses. Mostly we would meet at Thami Mnyele's place. Sometimes we would stay overnight. At this stage Thami was working as an artist [for the South African Committee for Higher Education]. We would sit there and listen to political debates. For example, they would ask why black people were supposed to carry passes and yet whites did not. They discussed the forced removals. Why black people attended schools which were of lesser standard to white schools in town? Those discussions made us aware that whites and blacks were living under different conditions."

Lazarus Mawela, who was introduced to Mnyele by James Moleya in 1976, remembers that he encouraged them to read and to debate issues.

"Mnyele demanded that people should read. He'd give you a book and say, "Next week you must come and tell us about this book." Then we would have a debate about the book."

Young people who had been in contact with activists like Mnyele, Moleya and others gradually took the BC philosophy seriously to the extent that they started discouraging black females from using skin lotions to lighten their skin. They targeted them in shebeens.

Gregory Malebo recalls:

"As members of the BPC we saw our role as conscientising people. Generally we would talk to them about their blackness; being proud of their blackness. We were discouraging ladies who were using skin lotions like Ambie. The idea was to try and instill a sense of pride in them. We realized that the effect of apartheid was not just chaining people physically but mentally as well. Our intention was to psychologically free people. In most cases we would use shebeens like John Moleya's and Mary's, because that's where we would find many people. We would receive heroes' status when we arrived in shebeens. You see, we were reading then and so we were able to express ourselves well in English. People appreciated that."

BC's influence filled students with a sense of pride about who they were:

"We were not as naïve as the authorities would have loved to think. You know there were songs like ‘tswang-tswang le bone ngwana o tshwana le lekhalathi' [Meaning ‘all come out and see our child looks like a Coloured' in Sesotho]. You see, we did ask ourselves, ‘Why do we think to be Coloured is more important than what we are?' How can you desire to be someone you are not?' So we could really put things into perspective."

At a later stage the BC's influence was to encourage secondary and high schools students to resist the government's decision to impose Afrikaans as a medium of instruction on them.

The National Party government, through the Department of Bantu Education, has as far back as 1955 promulgated a policy to have black students at secondary school level use English and Afrikaans as the media of instruction (students at lower and higher primaries were allowed to use their mother tongue). However, it failed to implement this policy because "... of the shortage of teachers who were proficient in both languages".35 Seventeen years later the government, again, attempted to implement this policy. Black schools, from Standard Four (today's Grade Six) onwards, were given two options: to teach all examined subjects in English or Afrikaans or to teach both on a 50-50 basis.36 Despite appeals and protests from black teachers' unions, in 1973 the Bantu Education Department (BED) officials opted for the 50-50 basis policy. In 1974 the Acting Secretary of BED sent a circular to regional directors and inspectors, asserting that the 50-50 use of both official language of instruction in secondary class would be maintained.

Michael Figo Madlala recalls the difficulty they experienced learning in Afrikaans:

"In Tembisa, students' concern over the use of Afrikaans began in 1973. In 1973 I was at Tembisa High doing my Form 1. My subjects were Maths, Arithmetic, History, and Geography, and Health Studies, and Agriculture, and Languages: Isizulu, English and Afrikaans. Other than the Afrikaans language, the other subject which we were taught in Afrikaans was Agriculture, Die Landbou. Teacher Molala taught us this subject. The first day in class he asked us ‘Wat is die grond?' (What is the soil?) How do you explain what soil is in Afrikaans? And communication was difficult because we had to respond in Afrikaans. [Someone] said ‘Die grond is bietjie things' (Soil is very small things). We could not explain, ‘Wat is die grond?' Then he read it out for us in the book what soil is in Afrikaans. But still we could not understand what that was."

- Michael Figo Madlala 3

Afrikaans was not only perceived as a difficult language to learn, but was also understood by students as a language of the oppressor.

Greg Malebo remembers:

I [was] doing Form 1 in 1974 ... You know, because Afrikaans was seen as an oppressive language ... many people hated Afrikaans. In fact, the majority of people in our class did not really want Afrikaans. The argument was that what [were] we going to do with Afrikaans? It was not an international language. We were unhappy.

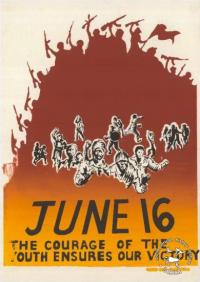

Students began to display their dissatisfaction as early as February 1976. Students at Thomas Mofolo Secondary School in Soweto clashed with their principal over the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction.40 In May Form Two (today's Grade 9) students at Phefeni Junior Secondary School in Soweto boycotted classes. On June 13 students in Soweto, comprising members of the South African Student Movement (SASM), a secondary and high school student organization, met to discuss the issue of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in black schools and to formulate ways in which other schools could support schools like Thomas Mofolo and Phefeni Junior Secondary. It was in this meeting that Tsietsi Don Mashinini is said to have suggested a mass demonstration on 16 June 1976 by all black schools in the township.42 On 16 June thousands of students from different schools marched in the streets of Soweto, carrying placards denouncing Afrikaans.

The police responded with brutal force, shooting and killing 13 year old Hector Pieterson. The student uprising spread to other areas. In Tembisa, students took to the streets in solidarity with students in Soweto on 17 June.

Michael Figo Madlala recalls:

"[On the 16th] we finished the day normally. It was on the 17th the headlines were in the newspapers ‘There's a march that had taken place in Soweto'. That was when in the morning at the assembly there was a feeling [that] something was going to happen. And very quickly the word was going around. We were then [directed] to a classroom where we then discussed as students the situation as it was happening in Soweto. Of course, there were a number of [politically conscious students] who were involved. You could sense from the way in which they were participating. One of these people who were in the leadership was Absolom Mazibuko. [In] that meeting we resolved that we [were] also going to march. And we said our march would go to Boitumelong Senior Secondary School because they were also affected by Afrikaans."

- Michael Figo Madlala 3

Just like in Soweto, police responded with force. Madlala, adds:

"We had already moved from Tembisa High. We were close to Boitumelong. We were somewhere in Mashimong [section] when we were disrupted. The police tear-gassed us and unleashed dogs on us. Students started running helter -skelter. [We] ran into a toilet. We got into a toilet - I'm sure we were about 15, if not 20, in one toilet. It was easy to go in but when we had to get out we couldn't because we were pressing the door out."

- Michael Figo Madlala 3

In the end, a number of students were arrested. Madlala continues:

"I think around the 21st we were then arrested. We were meant to have a meeting at school and the police encircled us. About 300 of us were arrested. And some [were discharged], then 105 of us were charged with public violence, alternatively arson. Our cases were then divided into three. Some were charged with three public violence; some with two public violence; and others [were charged] with only arson. If you were charged with public violence they would always put an alternative [charge of] arson."

- Michael Figo Madlala 3

Madlala and Brian Mbulelo Mazibuko were charged with sabotage and sentenced to five years on Robben Island. The two were to play a leading role in the formation of political structures in Tembisa in the 1980s.

Madlala and Brian Mbulelo Mazibuko were charged with sabotage and sentenced to five years on Robben Island. The two were to play a leading role in the formation of political structures in Tembisa in the 1980s.

In 1976 some of the students from Tembisa fled into exile to join the ANC. Andrew and Thabo Maphethu, sons to Reverend Phenias Maphethu were amongst those who left the country.

Less than a month (on 5 July) after students erupted against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, the BED Minister, M.C. Botha, publicly announced the department's decision to rescind the policy of 50-50 basis media of instruction.

NEXT: Development of competing political ideologies

1. Interview with Mongezi Maphuthi by Tshepo Moloi, for the SADET Oral History Project, Tembisa, 28 September 2004.

2. Interview with Jaki Seroke, conducted by Tshepo Moloi, Cosmo City, Johannesburg, 11 November 2011 [Tshepo Moloi’s private collection].

3. Interview with Mike “Figo” Madlala by Tshepo Moloi, for the South African Democracy Education Trust (hereafter SADET) Oral History Project, Kempton Park, 7 September 2004.