The Bakwena baMogopa community, having worked as labourers on "Free State" farms, grouped together and bought their first piece of land, Zwartrand, in 1911, in the Ventersdorp region, and later acquired another farm, Hartebeeslaagte

This indigenous polity was organized along communal lines and headmen represented their family lines, or kgoros. There was not an overall chief in Mogopa, but rather a senior headman, as the paramount chief of the Bakwena people was in an area near Brits.

By the 1980s, there were two schools, a clinic, shops, a reservoir, and a thriving agricultural sector. Mogopa farmers sold crops to the local agricultural co-operative, besides catering for the community.

As Mogopa resident, Victor Mogomotsi explains:

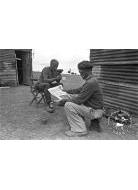

Before we were removed the land was used for various things such as agricultural purposes such as mielies, white maize (...for mielie meal), and yellow maize (the purpose for this was to feed the animals) and beans - and the purpose for those were to make an income. There was also sorghum. They would sell it ... and vegetables were planted in the individual yards.

There were also clear leadership structures within the community, as described by Philip

More:

in each clan there was one. One would ask to come into the clan and when you enter the clan you would be given rules and they would say that they are giving you a place to stay and regarding the farming you would not be privileged to have any farming land. You did not have any say, but you got a place... you could do what you wanted to do in your land and we could give you cows as well but you would not have separate farming land. These clans had very big rules or administration as you cannot just come and do what you wanted here...

All these clans would meet and they would have Rra Moloi to represent us and we told him what needs to happen or what is happening and he needs to listen to the rules of the clan. What would happen from then - you would be called or you would be paid, if there was something that needed to be done. For example, if the windmill was broken, you would all assist to fix it so that the community can have water. When they put streets up, they called the community ... and you were informed that they are going to put streets up

According to Andrew Pooe, the land was shared out, and shared by the community:

...each and every family was allocated a plot where we can farm. There was no one who was deprived from farming and there was not that people were not given an equal privilege. It was just a matter of being given the land and everyone given permission to farm. And those who managed and had the energy to farm, with huge space of land, others didn't have that energy. They had small land. That is how the land was allocated. There was no one who was deprived, it was purely common.

There was a primary school in Mogopa called Swartkop Primary School but initially older children had to leave Mogopa in order to attend secondary school in Ventersdorp and Lichtenburg, Men also travelled to other towns, in search of work to supplement the income from crops in Mogopa. Later, a secondary school, Kutlwano Secondary School, was built. According to Andrew Pooe:

...our school was one of the best [in the] Western Transvaal because it was able to attract other kids from outside, it wasn't just attended by the Mogopa kids. It was Carletonville, Randfontein, and others were from Soweto, Potchefstroom, Klerksdorp, Koster, Coligny, Bloemhof, Schweizer-Reneke, it was a big school that could attract students from outside.

Steps of the demolished school in Mogopa, December

The people of Mogopa talk of a great sense of unity and mutual cooperation in the time before the removal. Matlakala Lucy Manamela recalls:

... Every household was friends with everyone. There was no one who used to go hungry where there are neighbours. There was no way that your child would not go to school because you did not have money and your neighbour had money- we all helped each other. Our parents helped each other to take us to school and high school if we were all there together. Life was great, we used to plant vegetables; if there was no father figure in your home who could plant vegetables for you, the other fathers in the area would make sure that you ate. If you had your piece of land, they would plant vegetables for you and ensure that you were taken care of as well. Life was very nice in Mogopa before the forced removals.

In the early 1980s the community had a problem with their new senior headman, Jacob More, and tried to lay a case of corruption against him and have him ousted from his position. The government was quick to take advantage of the situation, with the local magistrate responding to this request by stating:

I as a white man and Magistrate of this whole area say Jacob More will rule until he dies."

Using the Native Authorities Act of 1927, the local magistrate said that he had the authority to keep Jacob More in power. Sensing an Achilles heel in the unity of this community, state officials started liaising with Jacob in the early 1980s about moving the community to an area called Pachsdraai, in Bophuthatswana, the demarcated homeland intended for all Tswana people.

Now they capitalized on the situation that was prevalent in Mogopa at that time because of the conflict between the community and Jacob More. So they capitalized on this conflict that this is the right time to come in. So they went in and destroyed the community. (Andrew Pooe)

Jacob was offered the farmhouse at Pachsdraai that used to belong to the white farmer that had owned the land before it had been expropriated by the state. As headman, he failed to consult the Mogopa community from which he was estranged over the corruption issue. In 1983, he moved to Pachsdraai with 10 other families.

Once he was gone, the State sent bulldozers to destroy the schools, churches and clinic. Trading permits for the shop keepers were no longer issued. Pensions stopped, and old age pensioners were told that they would only be able to collect their pensions at Pachsdraai once they had moved. The bus service to Ventersdorp stopped, and the water pumps were removed.

"The government was hoping to demoralise the community and force them to leave ‘voluntarily'."

Virtually we were left in an island; we were totally cut out from the world. There were no schools, churches... (Andrew Pooe)

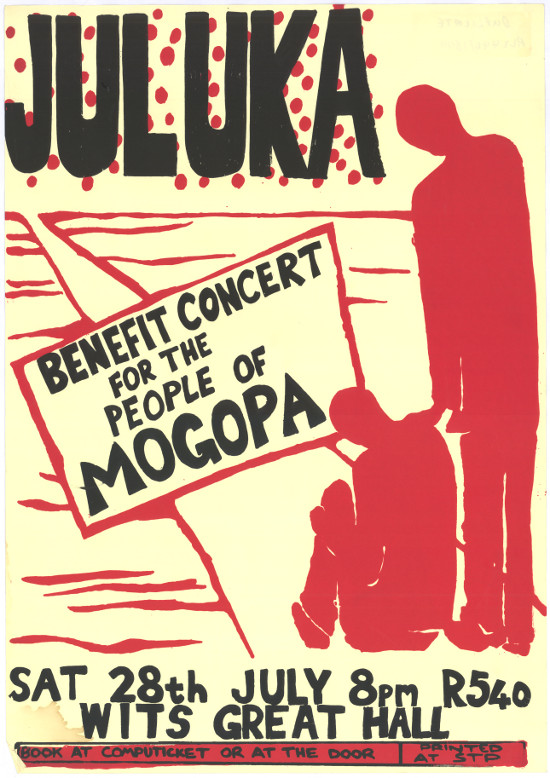

Giving in to this pressure, 170 more families moved to bullying tactics to strip them of their land, citizenship, and source of income, plus all the other value their land and birthplace held. The remaining families were issued a removal order and told they will be removed on November 24, 1983. The night before the removal, representations from the United Democratic Front (UDF) , including black Sash leaders, the media, the church, attended a vigil at Mogopa, tactic that succeeded in halting the removals.

Buoyed by this victory, the school was rebuilt by the community, with the help of the SACC, between December 1983 and February 1984, and through legal action the bus service and pensions were reinstated.

But the state was simply playing a waiting game - in the early hours of the 14th February 1984, with no warning, Mogopa was cordoned off and the police moved in. People were loaded onto trucks at gunpoint and taken to Pachsdraai.

"The leaders were handcuffed and put into police vans, doors of homes were kicked in and women were carried onto the lorries."

No journalists were allowed into Mogopa, neither were embassy staff, from the UK and USA embassies, black Sash nor TRAC fieldworkers. White farmers from the area were, however, allowed in in order to take advantage of the situation. They bought cows at bargain prices as the panicked residents were loaded onto trucks, fearing that if they did not sell their cattle, they would be stolen in their absence.

The white people had taken over and they had their things here and they were happy here in our place. They ate all our goats, cows. The white people ate our things. When we need our land back today, they are now talking about compensation but when they took the land from us they did not talk about compensation ...(Chief Mamogale More)

Many old people found the removal deeply traumatizing. Caroline Yvonne Tladinyane's father was forcibly removed in an ambulance as he was bedridden, and placed in a shack.

The people who were forcibly removed were adamant that they would not stay at Pachsdraai: it was arid, hot, and unsuitable for agriculture. They also mistrusted Jacob More, who had already made it clear to the dissidents that they would not get trading licenses, and pensions under his rule.

The Mogopa men who worked in Johannesburg had formed a committee to try and get the land back - it was called the Reef committee. They approached TRAC and lawyers in Johannesburg, for help:

...where they moved us to, it was difficult. We could not do anything that we do traditionally. If a person passes away there are ways that we do things. It was difficult to do things traditionally when they moved us to where they moved us. Some of the things we missed - majority of us believed in ancestors and it was difficult because when you do a function ...your ancestors are far away. This is one of the issues that forced us to do this was because we cannot be far away from our ancestors. (Victor Mogomotsi)

Women were also galvanised into action. Youth, who were normally excluded from community decision making processes, were also now able to participate:

... this removal was not discriminating, either on gender or whatever. So men and women stood together.

I remember some ladies who organized themselves moving around and also holding meetings, moving around and collecting donations from the very same community...their rule was visible, ... they played an important role in the decision making in organizing and meeting... things changed after 1983, after the removal itself, after that one-year. So there was no discrimination, young boys, women, young girls, we all went into the same meeting.

(Andrew Pooe)

The community applied for an interdict on the basis that they were not consulted and that Parliament was not consulted about the removal. In response, the state asserted that they did not have to be consulted in terms of the Black Administration Act of 1927. To reinforce this exclusion, the Department of Co-operation and Development Amendment Bill was drafted in 1985, with a retroactive clause which stated that the approval of Parliament was not necessary for the order to have been issued. While the tribe awaited an appeal of their case, the government expropriated Mogopa, with no notice, so that even if the tribe won the court case, they would be trespassing if they returned to their land.

In the meantime, the tribe packed up, left [Pachsdraai or Mogopa??] with the help of TRAC and the SACC (South African Council of Churches), and sought refuge in Bethanie, where their paramount chief was based.

But life was not easy for the Mogopa refugees. Bethanie was in another part of Bophuthatswana altogether, near Brits. They were faced with a range of social problems that come with living in limbo. They were divided up into three separate areas, as there was insufficient space for them to live together. They had no farm land, low water supply, no pensions and no chance of work as their reference books were registered back in Ventersdorp. This meant they were not regarded as residents in the area of Brits, as work seekers. The community members of Mogopa would have had to apply for Bophuthatswana citizenship to work in the area. As they retained their old SA identity books, these labeled them as being registered as work seekers in the area near Mogopa, Ventersdorp.

While I was in Bethal [Bethanie] I was working but I saw people that were suffering. There was nothing that was happening. You had to all organize: if you were going to buy food, you would combine and get transport for all of you and then take out money to get food in Brits or Rustenburg.

People suffered during this time. During this time there were no people that were working; the only people that survived were the people who had people working in Gauteng. They survived better. But you must remember because we were at the forced removals now and we were looking at one person who was working. It was not the same as when we were at Mogopa when we could farm and get vegetables and help each other out. It was very difficult during this time. (Matlakala Lucy Manamela)

Here too, they were under Mangope's rule - as he was President of Bophuthatswana. He did not take kindly to the fact they had resisted going to the area designated for them in "his" homeland. This meant that the Mogopa people had to be careful of what they said while in this homeland. They had been divided into three villages, which made meeting difficult.

"Bethanie was like a jail because we couldn't move an inch, we couldn't do activities, the only activities was to play soccer in Bethanie, we couldn't even hold meetings and so on, we were under the oppression of the old Bophuthatswana laws".

Ishmael Pule Mohutsiwa

But life was never the same as in Mogopa because we have those people from Bethal and they have their own culture and their own living. Here we are coming with our own lifestyle, everything changed... What we experienced was very difficult; there was so much frustration. It was the kind of frustration that morally and socially ... things don't go well, we started experiencing teenage pregnancy, we started seeing a lot of people indulging in alcohol, some families were destroyed. .. We didn't have anything to do. Job prospects - there were no job prospects and that is why there was so much alcohol because when everyone wakes up, what do you do? It was hell, it wasn't the lifestyle we were used to. It ended up being a free for all, without direction. Mogopa life was destroyed and it's never been the same again even though we came back...

you'll remember that it was Bophuthatswana...We fell under wrong structures, they could not allow us to hold the meetings...until we had a youth movement... and no decision could be taken by elderly people without consulting us. They would ask us is this right or wrong when we do this? Then we kept them together stronger because they saw that we're serious as youth in the community. (Andrew Pooe)

TRAC and SACC worked on a plan to buy alternative land for the community at Holgat, an old mission farm, in 1987. But just before the community could move, the government expropriated this farm too, claiming it was needed for an agricultural college.

In a historic judgment in 1987, the Supreme Court declared the Mogopa removal had been illegal. However due to the expropriation of Mogopa, the tribe was not free to return to their land. The Mogopa people negotiated with the government insisting they would accept no place other than Mogopa to live. In 1987, the government offered them a place at Onderstepoort near Sun City.

Some of the community moved there whilst others stayed at Bethanie, too tired and demoralised to face another move. While the community discussed what was the best way ahead,people differed out of fear or approach, and the once united community split even more. Distrust developed.

...we didn't trust each other first of all, because some of us took things that we discussed outside, then the following day you will be seeing police harassing some of the members of the community. So the relationship was not good. It was just good with few that trust each other but truly speaking there was a mistrust within the community , so you had to be sure, who are you talking to, what will you be doing in that particular time of the day. So it was not like before where people in Mogopa were united.(Pule Mohutsiwa)

While the tribe was at Onderstepoort, Boitumelo Manamela was a young girl - about 6 or 7 years old, and she remembers:

"We lived in a shack and it was very hot and at night you could not have a good night's rest as there was also no electricity as well....There were a lot of us that stayed in the shack... more than five of us in one house. To cook we would need to make a fire ... however if you had your own stove, you would cook on the stove."

From Onderstepoort, some members of the community decided to simply return to Mogopa. This was largely in part due to the youth starting to organize themselves and start playing a more active role.

Then we started the youth group and it was called Mogopa Youth Congress. I remember we even had t-shirts for that. (Ishmael Pule Mohutsiwa)

Youth had already started trying to meet and organize themselves in Bethanie under the pretext of playing soccer, but it was difficult as the community was now separated into three areas there, but the organisation firmed up once in Onderstepoort:

Our plan when we were there is that we came up with the Youth when we were at Onderstepoort. We started to interact with our parents and the leadership there and showing each other our problems. The Government ... promise was that we were going to stay there for only one year but it was going on two to three years. Now, what is our next move? We sat down and started thinking and we have to come up with something tricky. That is when we decided to close in on Viljoen to get permission to clean up the graves; then if we get the permission then that is how we are going to stay in Mogopa.

(Victor Mogomotsi)

In 1988 they secure permission for the old people to clean the graves of their ancestors at Mogopa, and those that went to clean the graves stayed and camped out on their land.

"We are not prepared to move from our land. We want to live here. If the government wants to remove us they must rather shoot us and move our corpses. We are not going anywhere again" (Daniele Molefe)

I was using the truck we had at home. What we used to do is bring their material at night. I was doing two trips. One trip at 6 - 10pm and the other trip from 10pm - 6am again travelling like this to bring the material of all the people. (Victor Mogomotsi)

Slowly more and more of the Mogopa residents joined them, camping out amongst the rubble of the demolished houses and facilities.

Attempts were made to evict them, but in the face of broader political developments, such as the release of Mandela, and the start of negotiations towards a more representative political dispensation, eventually the government agreed that they could remain, and one of their farms, Swartrand, was restored to them in 1991.