In 1912, in the light of the pending Land Act, a group of farmworkers in the then Eastern Transvaal, bought a piece of land called Driefontein, by selling cattle, and registered it in the name of the Native Farmers' Association. One of the main people behind this idea was Pixley Ka Seme, of the SANNC (South African Native National Congress). The land was subdivided into 310 plots of 10 morgen (about 21 acres) each. Over subsequent years, these plots were sold to individuals, some of whom bought two plots. By 1985, there were 250 plot owners in Driefontein.

The community was first approached by the government about its plans to remove them, in 1965. The landowners made it clear they did not want to move:

"My father bought 10 morgen at Driefontein in 1919 from the Native Farmers' Association. Why would we move from places where we were born and where we want to die?" (Mr. V Manqele)

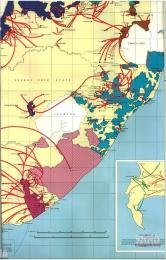

In 1983, the government once again told the community that it would have to move. This time the reason given was that the government intended building a dam on one section of the farm, and it would cover 25% of the plots. The given rationale was if these people would lose their plots then the whole community would have to move. The designated place of removal was Oshoek, in the Bantustan of KaNgwane. Another place mentioned in KaNgwane as a destination was eLondweni, or Lochiel. This was for the siSwati speakers. The isiZulu speakers would be moved to Babanango.

Not all Driefontein residents were Seswati speaking. Many were Zulus. There were also a few Sotho residents. This made a mockery of the policy of homelands being allocated to designated ethnic groups. At this time, hearing the resistance of the people to moving, the government tried to remove the democratic structure that managed Driefontein, and replace it with a Government imposed Driefontein Community Board.

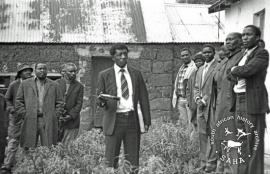

In response the community elected a new Board of Directors, with Saul Mkhize as its head.

Saul made it clear that the community opposed any threat of removal. As a result, the government put pressure on the community: old age pensions and public transport to Piet Retief and Ermelo was halted. Trading licenses were not renewed.

The community responded by taking legal action against these strategiesmarching on the offices of the magistrate in Ermelo and exposing, through the press, the government's tactics. A legal clinic was set up in Driefontein to assist residents and farmworkers in the surrounding farms. The latter were being retrenched and removed from farms in the area in alarming numbers at this time, and evicted farm workers were asking for a place to stay on Driefontein.

The response of the State was to take the gloves off.

On 2 April 1983, Saul Mkhize was conducting a meeting at Qalani primary school, when Constable Johannes Nienaber, a policeman from Piet Retief, arrived and told him he did not have permission to hold a meeting. Saul said as head of the elected Driefontein Board of Directors he was fully in his rights to hold the meeting. The angry crowd demanded the policeman leave. The policeman left the premises, and then, from behind the gate outside the school yard, fired at Saul Mkhize, who died of the gunshot wounds. The shocked community felt this was a cowardly act ( Zwli Sidu)

The people were low and there was a fence which was 4m high and the others were this side and the white man was on the other side of the fence and they would run to the fence and they would hit the fence with these sticks that they had and they would climb the fence and they would fall down and take their sticks and run.(Shelley Shelembe)

The community was astounded that the rhetoric of the government was that of voluntary removals, but through the killing of Saul, the State had shown what lengths it would go to, to achieve its purpose. Legal action and press reports continued against the removals, and Beauty Mkhize, Saul's widow, was elected as Saul's successor on the Board.

The state also tried to install chiefs in Driefontein, to appeal to people's ethnicity and offered Zulu people a place in Babanango, part of the KwaZulu homeland.

Still people refused. Another tactic was to attempt to divide landlord and tenant but this too failed. (building of clinic?)

TRAC approached Enos Mabuza and invited him to a meeting at Driefontein. Mabuza had made it clear that he was not interested in accepting independence for his homeland, and had stated in the press that he was against the plicy of forced removals.He addressed the people and, having heard they did not want to move to his homeland, he said he would not accept people that had been moved by force into his homeland.

Coupled with this, a forestry company, Lotzaba Forests, affiliated to Barlo Rand, offered land near Driefontein to the Government for purchase, that could be used to compensate the people whose plots the planned Heyshope Dam would cover.

With the two main pillars of hope for the removal to proceed smashed, the government reprieved Driefontein in August 1985. The people were elated. Their struggle for the right to keep their land was over. However, the struggle for autonomy was not over. In the early 1990s government tried to replace the Driefontein Board of Directors with a community authority, and to limit the number of people on the land. Later there were attempts to install a Zulu Tribal authority over the people, and to establish an Inkatha stronghold. This divided residents, and clashes occurred, and at least two people died. There were tensions between the Board of Directors in Driefontein, as they were supportive of the ANC, and the tribal chiefs and those who supported Inkatha.

Youth in the community were also involved in these tensions and "Shelley" Shelembe remembers the formation of the Driefontein Youth Committee, DYC, to assist the elders in fighting forced removals. Saul Mkhize approached him and someother youth members to play an active role, and thus he joined the Driefontein Board of Sirectors and attended meetings, with Saul and other community leaders, to discuss the removals.

we did it mainly that we will not move from where we are. That was our slogan and it was that we will not move. That is when we sat down and discussed the whole matter ... It was formed through Mkhize as there were youth movements that were present in that time and these were Inyanza [youth movement] and IFP Youth Brigade.

(Shelley Shelembe).

The core of the people's organization held the community together despite attempts to divide them and destroy their sense of victory.

"The first task was the fight against removals. After we won the reprieve, we then focused on development...electricity was installed by the help of the Board of Directors, for water to be pulled in by pipes. ...through the help of the LRC and black Sash". (Jane Vilakazi)

Many residents of Driefontein stressed at the time that there was a shortage of land for residential purposes, with only the farmers and a few tenants stressing the need for more land for grazing and ploughing. Historically Driefontein has been a place of refuge for waves of people evicted from farms during forced removals or drought periods under Apartheid.

Zeblon Ndlangamandla explains how he came to Driefontein:

"I left Bethal where conditions were very bad and was given a place here in Driefontein. In exchange I helped the land owner with farming. He had about 20 cattle. Then when the major evictions from white farms started taking place after 1965, his relatives started coming in and asking for place. By 1983 there was only grazing for three cattle. Today the place is full up. Most of the people, being relatives, are not even paying the owner anything."

By 1985 there was a severe pressure on the land.

In 1985 there were no farming extension services to Driefontein. Maize, beans and vegetables were the main crops, and mostly for own consumption. This was all families could grow as the average size of a plot was1 hectare for most families. For the landowning families who had preserved most of their original purchase and occupied a 24 hectare plot, some commercial farming took place. Cattle were used for milk, meat, manure and lobola.

Jane Vilakazi, once a member of the Driefontein Board of Directors with Saul Mkhize, remembers people bartering with each other for different products that they had grown. She came as a young bride to Driefontein,in 1980. She came from Meadowlands, Soweto, where her family had been moved from Sophiatown, in 1955. Her in-laws were from Bethal, and they came to Driefontein first as tenants but later bought the plot from the original owner. She feels the community has come a long way in terms of electricity and flushing toilets but feels the land is underutilized.

When interviewed in 2013, Jane Vilakazi also felt that there was enough land for people to farm, but some were not interested or just lazy. Post 1994, extra land has been bought by the community, including Masihambisane, Tshabalala, Lindelane, Mkhizeville (with RDP houses), etc but extra people have continued to settle on the land from neighboring farms. Grazing land is always short and although there are some successful farmers who grow mealies and sell them to cooperatives, most people do not exist off the land. Some grow beans and vegetables for their own use, but few are commercial farmers. Cows are to be seen on certain of the landowners' plots, and arrangements have been made with local landowners for extra grazing as well. There is a farm Driepan, that is apparently owned by Daggakraal and Driefontein, but the community is not accessing it according to Jane Vilakazi, but she is not sure why.

Driefontein now falls under the municipality of Mkhondo, along with KwaNgema, Iswepe and other farms. The Driefontein Board of Directors was disbanded and Councillors elected. They are paid by the municipality and Beauty Mkhize feels as such their sense of accountability to the people of Driefontein is not great. There is little consultation with the community over issues affecting them. The Department of Agriculture has provided 10 tractors, with ploughs, to the broader Mkhondo area, for use by farmers, along with free seeds. Training courses are offered, although these are not regular. Silos have been built at Masihambisane to store grain.

Most of the people in the community grow vegetables to eat - not to sell, according to JaneVilakazi. She also said that the land at Driefontein - including all the extra farms that Driefontein has purchased over the years, is under pressure due to settlement, and not much is available for farming...One of the landowners, the Mkhize family have more than twenty tenants at their plot. This is not necessarily lucrative - as Beauty Mkhize pointed out:

"tenants here only pay rental once a year. For example those living in the Mkhize homestead they're paying R50 a year...but they don't want to pay that money...if you chase them away where would they go? ...and we fought the resistance together with them...we decided to look for another farm where the tenants could purchase land and build their homesteads...Masihambisane. Each plot owner paid R700 and the government paid in an equal amount to purchase the land, according to MrDlamini. An extension was established in Driefontein where RDP houses were built. More sections were established like Lindelane, Tshabalala...the ANC was in power (by this time). The officials came and said that we should have a place where we could store our maize after harvesting, because they were running a project called Masibuyele e masimani (let's go back to tilling the land). (A mill was built near Driefontein to help people grind their maize). ..at Masihambisane each person owns a stand which is two hectares in size...this allows each person to even have their cattle and other animals to graze there and to till the land. .. the major problem is that the landowner cuts a piece of land for the tenant. So it becomes difficult for anyone to farm the land..."

Even Beauty Mkhize uses land belonging to a white farmer, near Piet Retief, to graze her own cattle at a rate of R4 per cow per month. She had 18 cows at the time of the interview in June 2013, and some sheep. She refers to other values of the plots that the landowners have:

"I decided to buy my own stand...so there's a big homestead where I lived when I arrived in Driefontein... (her late husband's) birthplace. ..I sometimes go to the big homestead to clean, cook and eat over there, then return to my place to sleep...the nice thing is we're united as a family. All the graves of the Mkhizes are in the big homestead."

Johan Sam Dlamini came to Driefontein as a tenant but later bought a stand at Masihambisane. He is now a farmer. He farms for himself and ploughs for others using the tractors and ploughs provided by the Department of Agriculture. Before this he used to use his own. He buys the diesel, planter and spray, and charges for his work. He belongs to a farmers' association formed by farmers from black communities in the area. Any repair work to the tractor can be claimed back from the government. Besides farming for others, and charging them, he farms 38 hectares at present for himself, using his land and that of others who do not want to farm. At the end of the harvest he pays back the stand owners whose land he has used, with produce. He farms other people's farms for them, starting from 6 hectares in size. In smaller areas than this, he says the government helps with farming for free - including chemicals and sprays.

He became very frustrated when asked about the Youth. His farming association at one stage under a Mr Dladla had offered the Youth in the area a piece of land, - of 2 hectares, and had asked a local white farmer for a water pumping generator for this piece of land. In spite of this, the youth did not pitch to become involved in the project. Dlamini feels they just want desk jobs.

"The youth is cared for but it doesn't want to work...they want to work in the offices. If you say to them, ‘while you are waiting for those jobs, work the land', they refused...there is one young man I asked to help me driving my tractor. He said he doesn't like to work Saturdays and Sundays. ..I work throughout the week started at 4 in the morning and I'll finish at 10 at night."

He described how the young man had arrived on a Saturday and was too drunk to drive the tractor. He then went on to say that it is up to how a child is raised in terms of the land.

"If a child grew up in a family where the adults didn't work the land, then the child wouldn't know how to work the land later. ...I work the land and my children also do the same...(they) finish off my work where I couldn't."

Right near Qalani school is a house that used to be owned by Hilda Gumede. She was a stalwart of the community and fiercely outspoken against the removal. Her house is now occupied by a couple who are currently employed by the national school feeding scheme, to grow vegetables that have to be delivered to a central point in Nelspruit whereupon they get distributed to schools where children are at risk. After growing the vegetables and taking them to Nelspruit for over three months, the couple has yet to be paid. They reported to Gille and me that they are running out of money and resources, and all queries to the official in charge of the feeding scheme in their area, have been fruitless.vbecome a housing settlement. Most people work for others in forestry projects nearby or have to leave and seek work elsewhere. Some people still have cattle, but there is limited grazing. The few people who do farm sell their maize to a company who makes mealiemeal.

When asked to outline their plans and dreams for the future, plus the challenges in the community, the Youth expressed their hopes either to stay in the community and make a difference as a farmer, or a teacher or a nurse, whilst others said they would leave as soon as they could due to the lack of jobs in the area. Some spoke of tourism opportunities in Durban. In terms of challenges in the community, Youth spoke about poor services, poor living conditions, poor education, teen pregnancy, alcoholism, and lack of job options for their future. They expressed frustration that they were not educated about how to develop or improve their area. Overcrowding was a problem and with it, crime had started - something new in their community.

The Headmistress of Qalani Primary, Mavis Luthuli, outlined how most of the Youth that have left school survive on about R500 a month that they receive by being part of the Community Works Programme in Driefontein, for working 2 days a week on average, doing basic CWP work that the community had identified. This included cleaning a hall, or repairing roads or visiting the elderly. The Mine in the area - Kangra coal mine provided a few jobs for the community as did the local forestry companies. She felt there was no real interest in agriculture expressed by the Youth, although the youth said they had not really been drawn into projects in the area that encouraged farming.