The administration of all these activities over such a long time span (17 years) was no small task, and with constant comings and goings and security threats to deal with, as well as political and military matters, it was a major effort to achieve orderly decision-making and implementation.

ZAPU never officially established a "government in exile", but they were in fact virtually running one - not to govern the country but to direct the war effort and manage the refugees. The period up to 1970 was more straightforward, as the party leaders established offices and built up diplomatic relations as well as developing an army.

Serious problems came in 1970 with the first sign of the split within the leadership leading to the formation of FROLIZI and mutinies among some of the cadres. For two years virtually no movement could take place on the military front, and from 1972 the whole operation had to be rebuilt - but rebuilt in the context of pressure from the OAU to form a combined effort with the other liberation movements.

Before that was resolved, the leaders restricted within Rhodesia were released and joined those in Lusaka, and at the same time the dramatic increase in flow of both recruits and refugees began. From 1976 to the end of the war there were continuing new political developments at the same time as logistics nightmares and yet dramatic progress on the military front.

The first administration in Lusaka was established in March 1963, when Amos Ngwenya was sent with Willie Musarurwa to set up offices. Ngwenya remained as the administrator until 1977. In 1964 Lusaka became the external headquarters, when Zambia gained independence and all liberation movements moved from Dar es Salaam.

Musarurwa returned home and was arrested and joined others in detention, but five executive members were sent to run the operation in Lusaka. The Vice President James Chikerema, and Jason Moyo took responsibility for military developments after the first trainees returned to Lusaka in 1965 and a high command was formed under the Department of Special Affairs.

George Silundika, Edward Ndlovu and George Nyandoro were the other members of the executive in exile, with Silundika taking prime responsibility for publicity, and Ndlovu assuming the role of a diplomat. Together these five built up the diplomatic and military strategies.

The effort was assisted by large numbers of Zimbabweans living in Zambia. As Ngwenya tells it:

We formed branches in all the major cities of Zambia. Livingston e, Choma, Mazabuka, Lusaka, Kabwe - which was Broken Hill at the time - Ndola, Luna shya, Kitwe, Mufulira, Chingola, Bancroft, and then also rural areas like Mumbwa, Liteta, these were areas with a large population of Zimbabweans; they all also belonged to ZAPU.

Charles Madonko was one of those members who played a key role as he was based in the Copperbelt, working for the railways:

Yes, I was running an office there. And therefore because I was busy with the railways so I asked the office to give me some guys who were not so busy in Lusaka. So th ey gave me Attwell and Butshe, and we worked together until I left Zambia for Hungary [to go to study]. While I was in Kitwe with Butshe and Attwell, I had the largest number of recruits from my province.

Besides recruiting the members would contribute funds through monthly subscriptions:

That was the purpose of the office, why I had those two guys, because they ... they would look after the finance and I would ... either Chikerema and Nyandoro would come there. So that`s what we did and therefore because the volume of the supporters in Kitwe, so I had to ask for assistance, and then I got these two boys.

The administration under Chikerema and Moyo continued up until 1970 and was responsible for the early military activities, including the major campaigns of Wankie and Sipolilo. But political differences produced a split which went along tribal lines when Chikerema and Nyandoro withdrew and formed a rival party known as FROLIZI. The quarrel also resulted in the military efforts coming to a standstill and that in turn produced mutinies from restless cadres in the camps who blamed the leaders for neglecting the struggle. Ngwenya tells the story thus:

The administration under Chikerema and Moyo continued up until 1970 and was responsible for the early military activities, including the major campaigns of Wankie and Sipolilo. But political differences produced a split which went along tribal lines when Chikerema and Nyandoro withdrew and formed a rival party known as FROLIZI. The quarrel also resulted in the military efforts coming to a standstill and that in turn produced mutinies from restless cadres in the camps who blamed the leaders for neglecting the struggle. Ngwenya tells the story thus:

... after the departure of Chikerema and George Nyandoro, you see in 1971 ... 1970- 71. We were detained There were also some young people who carried out a mutiny, arrested the leaders - this was 1970; then the Zambian government intervened, then took everybody to a camp - Mboroma that's where we were camped there; and then they asked one of their senior officials - Aaron Milner who was the Secretary General of the Zambian government - to assist to, to solve the problems there and then he did that.

The mutineers were handed over to the Zambians and most were eventually sent overseas for academic studies.

The remaining leadership returned to Lusaka and set up a new decision-making body, the Revolutionary Council which would have representation from both the politicians and the military. Later administrators were also added. Jason Moyo now was elected to chair the Revolutionary Council and Dumiso Dabengwa was the secretary. Alfred Nikita Mangena became the new military commander. Under this new arrangement, the military was rebuilt and ZAPU's role in the armed struggle surged forward.

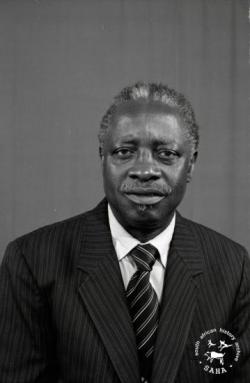

Jason Moyo is remembered with great respect by most of his colleagues. Says Ngwenya:

He was a very courageous person, discipliner, some of us did a good job because of his discipline positions [inaudible] yes and faithful, he would not listen to lies, in fact, you could not tell lies to him.

Mtshana Ncube saw him very much as a team player:

... the Revolutionary Council was an active body that seemed to me at the time to take over all of the duties of what might be the duties of a President in an organization and although all of us knew that the head then was JZ Moyo it seemed he did not want to put himself too much in the limelight. Whether this was by design or whether this was by structure I couldn't ... I couldn't say, but I know that he seemed to work very much in concert with a number of other comrades to produce whatever decisions needed to be produced and then he would publish them or read them when necessary.

JZ Moyo was the focal point there, and very, very well respected indeed... a man of very few words, but a man of great effect. When he spoke he spoke because he had to speak, and when he spoke he spoke what moved the people, and that's how I remember him and I sometimes wonder whether some of the leaders shouldn't learn a great lesson from JZ Moyo - that it's not the speaking and it's not being present in the eyes of the people every minute that makes the difference. It is what you bring to their eyes, what you bring in terms of action, what you bring in the few necessary words that makes the difference. And JZ Moyo had it.

The Revolutionary Council then took over the functions of the former executive, although the executive was not dissolved and remained in existence. The council was apparently very active, as recalled by Ncube:

... it created the impression in my mind that they had taken over the functions of the executive, because they seemed to be always in session and maybe this of course explains the times also, because these were very busy times at the military front, so that perhaps emphasis would necessarily shift to matters military than ... than civilian.

Another feature of the mid1970s was the constant insistence by the frontline states, that the various Zimbabwean parties should come together in a joint effort. With FROLIZI, the ANC of Muzorewa was also added to the mix; after successfully organizing a "no" vote for the Pearce Commission in 1972 on behalf of ZAPU, it then took on a life of its own:

In 1974 there was a ...we had a unity accord that was actually im posed on us ... that is, all political parties in this country, ZAPU, ZANU and the ANC Zimbabwe National Council that was led by Bishop Muzorewa to organize people to oppose the Pearce Commission ... so it had become a party that was operating ... so then the Frontline states, Botswana, Zambia and Tanzania you see well initiated it... this unity accord, I remember it was in November 1974, I can`t remember the date.

This was not the first attempt to force unity, but the situation became far more complex when the imprisoned and restricted leadership of ZAPU and ZANU were released by Ian Smith at the end of 1974, and internal struggles in ZANU led to the assassination of Chitepo in Lusaka in 1975. Once released, Nkomo did not immediately leave the country to base himself in Zambia. This only happened later, after the assassination of Jason Moyo by a parcel bomb in January 1977.

The death of Moyo was a great loss to ZAPU. Ncube recounts:

... I had just left the office. I could have died in the office on the same day. I don't think it was even 15-20 minutes after I had left the office when the e xplosion ... went off and that brought quite a sad atmosphere throughout the liberation movement and I think for a while I might not be exaggerating if I say some paralysis because we didn't know what that might mean in terms of our operations ... the direction, the effectiveness, our ability to collect resources, our ability to connect with the international community to say we are still there ... all of that became a big question mark.

It was at this point, then, that Nkomo decided to leave Rhodesia to base himself in Lusaka. Of course he had been visiting frequently since his release but now he came to take over the administration. Says Ngwenya, "instead of appointing someone to lead, to replace JZ Moyo, he chose to come outside to lead the party".

Those final years of struggle from 1977 to 1980 were ones of intense activity. Not only Nkomo but several other of the detained leaders came to Zambia, as well as thousands of members who could be drafted into administration instead of the military. It was not easy to fit all of them into a coherent structure where everyone feel useful, would know their place and perform effectively.

However, due to the development of military activities and the flood of refugees, there was far more work to be done, so administration had to be expanded. New offices were constructed at Zimbabwe House in Emmasdale to accommodate all those who had to manage the logistics, the publicity and general administration of people coming and going, needing accommodation, passports, visas, food and offices. Nkomo took charge of operations himself and it seems that his style was somewhat different from JZ Moyo's.

However, due to the development of military activities and the flood of refugees, there was far more work to be done, so administration had to be expanded. New offices were constructed at Zimbabwe House in Emmasdale to accommodate all those who had to manage the logistics, the publicity and general administration of people coming and going, needing accommodation, passports, visas, food and offices. Nkomo took charge of operations himself and it seems that his style was somewhat different from JZ Moyo's.

Ncube recalls:

Nkomo for whatever else people may have thought of him ... he was a man who understood the mind of the people. He understood very, very well. ... he also understood the ... need to mould an organization. He understood it very, very well. One of the ways he did it, he had to bring himself forward to be leader of the organization, and being leader of the organization didn't mean being President of ZAPU only, in the overall sense, but also being able to be leader of the units of ZAPU. Like the military, hence that uniform.

Nkomo had to draw together not only the military and the civilians but also those who had been in exile for ten years or more and those who had been sitting in restriction at Gonakudzingwa.

Ncube speaks about the tensions but also about Nkomo's strong leadership and ability to provide the unifying glue:

There were [tensions], yes, as there would always be in any movement, because you are talking here of ... not only are you talking of different class backgrounds, you are also talking about different orientations in terms of knowledge, people who have been exposed to all sorts of ideas coming together to try and sit with someone who hasn't got a clue where the world starts and where it ends. Naturally there would be those tensions, and the differences were felt, however, I hasten to say in many instances they were handled quite, quite correctly, in discussions.

The Revolutionary Council, however, lost its central role in decision-making and became more of a consultative body, with the critical decisions being taken by the military and intelligence leadership along with Nkomo and his senior politicians. Ncube discusses all these issues as well as the burgeoning administration having to handle both military and refugee logistics as well as diplomacy.

Once again the ZAPU membership in Zambia became of critical importance in assisting. The branches were active throughout Zambia, under the leadership of Desire Khuphe the chairman of ZAPU's Zambia province. Frequently meetings were held at Kabwata Hall in Lusaka, in rural areas such as Mumbwa and at homes in urban areas.

In addition to the earlier roles of funding and recruitment there were new functions added for the members. Charles Madonko played a particularly important role as a farmer. After returning early from Hungary he entered the University of Zambia to study agriculture, however again he did not complete but joined the Zambian Ministry of Agriculture's research institute. From there he was asked by the party to obtain a farm, which he did with the help of the Zambians. Then he began to provide food for the military and the refugee camps:

I was growing vegetables, I was growing huge acreage, like 10-12 hectares of vegetables, where from the camps the guys would come and pick up the vegetables... and beef. I had money from the party to buy beef on the commercial farms... the cattle would stay on the farm, then they would come weekly and slaughter two, three up to ten ...

The Mulungushi Camp which trained the regular army was his main responsibility, but he also supplied food for the women at Mkushi Camp. When they were attacked he, along with members in Kabwe, played a big role in rescuing the survivors and getting them to Kabwe hospital. Before moving to his farm in Mkushi Madonko occupied a smaller farm ne ar Lusaka, where he regularly accommodated some guerrillas who guarded caches of arms which he stored for ZPRA.

These were the roles which a member could play; few were as active as Madonko. But without people like him it would have been difficult to manage such large numbers of military cadres and refugees.

Mtshana Ncube discusses how the administration attempted to deal with so many issues at once, and also goes into a little more detail on the manner in which education was handled. He talks about how not only members living in Zambia but also many of the administrative personnel could easily become confused about the overall plan and progress towards the ultimate goal. Hence an overall strategic vision was drafted and communicated to the party members as well as the general public.

This vision was known as the "Turning Point". Most other interviewees as well as writers of ZAPU history have understood the Turning Point as a purely military strategy. Probably that was what came across most clearly to the public, but Ncube, who drafted the document which was read by Nkomo at a press conference, presents it as an all-embracing vision which was meant to inspire and motivate all members.

This vision was known as the "Turning Point". Most other interviewees as well as writers of ZAPU history have understood the Turning Point as a purely military strategy. Probably that was what came across most clearly to the public, but Ncube, who drafted the document which was read by Nkomo at a press conference, presents it as an all-embracing vision which was meant to inspire and motivate all members.

Interestingly enough, this new strategy was taken so seriously that every member of the Revolutionary Council, being privy to further information that was not released to the public, participated in a signing ceremony during which they had to pledge to secrecy:

So we were signing what was called a secrecy agreement which each individual leader was asked to sign - swear and sign - before the President, affirming their own understanding that they were being held responsible if any information should be leaked which they came to have by reason of service to the struggle.

Various aspects of the administration are referred to in many of the interviews. It was a complex thing, running several departments, especially towards the end - a large publicity department with its own printing press and photo laboratory, schools for several thousand children, transport, even a research unit, and few individuals would have had a clear grasp of the many processes at work. The fact that it worked at all and moved the struggle forward must be a tribute to the dedication and leadership qualities of many.