Oral history plays an important role in our lives. This section will look at some of the reasons to study oral history.

Education

Oral history gets learners "to develop an understanding, not only of the broad history of South Africa, but also of the richness of the histories of their local communities."1 The study of oral history gives us unique insights into "the personal thoughts of thousands of individuals from all walks of life."2 Oral history challenges learners to go beyond an understanding of history as a series of facts and figures. It also helps the development of "imperative research skills" such as attention to detail and critical thinking.3 This means learning how to use logic and reason "to analyse and sift out what is useful."4

The South African Department of Basic Education (DoBE) has recognised oral history education as a very effective method for learning. To celebrate this, a nation-wide oral history competition has become an annual highlight of the Department since 2006.

Heritage

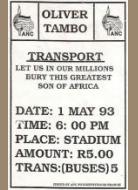

Oral history helps to identify, appreciate and respect different aspects of heritage. This includes the people, events and experiences that have shaped our personal lives, our communities and our national identity in different ways. Heritage is a "consciousness of the past that gives us individual and collective identity."5 Oral history thus makes it possible to focus on what the past means to us. For example, oral history has helped fill in the gaps of how struggles against apartheid unfolded, both in South Africa and abroad.6

Senrika Govindasamy, a Grade 10 learner from Chatsworth, conducted an oral history project to find out more about her heritage as a Hindu Indian. She has shown that heritage is not always about important people, politics or places. It is also about understanding our roots. Through interviewing the chairperson of her local Hindu temple, she got "way more than (she) had expected when (she) learnt how much the people in (her) community had to go through to finally achieve the vision of the elders before them."7

Healing

During the apartheid regime, millions of South Africans were denied most basic human rights, including the right to know and the right to be heard. One oral history educator has pointed out that "as a result of the heavy censorship under the apartheid regime, it is inevitable that, at some point, information would be manipulated."8 Oral history makes it possible for this information to rise to the surface. Remembering the past can be a painful experience for interviewees, but it can also help them resolve their experiences.

The end of apartheid marked the beginning of an era of prosperity and freedom, but for many, little changed. One returned exile, Bongiwe Njobe, interviewed in 1991, said that "many people subconsciously thought that it will be very easy in the new South Africa."9 But the promise of a new society was not felt so easily. This was expressed in an oral history interview conducted in 2007 with Rammolutsi resident Mokete Tsotlotlo (MT) by field workers Dale McKinley (DM) and Ahmed Veriava:

DM: Tell me what kind of things changed? What changed for the better for you?

MT: There is only one change that took place - this house that I'm living in. But here in the community, things have not changed much... the houses, the rubbish. Even the water can be shut down anytime and when it comes again it is not clean, not good for people to drink, it's smelly.10

McKinley and Veriava's interviews have been published through the South African History Archive in a book called Forgotten Voices in the Present. The interviews gathered in this collection show the value of oral history as a platform for expression, healing and hope.

References

9 Njobe, Bongiwe, Interview, SAHA Exiles Project (AL2461_10_p1_10), 27 January, 1991