It is barely half a year since the historic announcement by erstwhile President Zuma that the government had decided to implement free education as a policy starting in 2018. While some saw the announcement as a desperate ploy to maintain power, but for #FeesMustFall supporters it signified a giant victory in a struggle that, unbeknownst to many observers, had been decades in the making.

Anyone who has some sense of political awareness should be familiar with the “fallist movement”. The phrase “Fallists” generally refers to those individuals who aligned themselves with the various “must fall” movements, including #RhodesMustFall #FessMustFall, #AfrikaansMustFall and the decolonization of the education system. The calls of the Fallists for free tertiary education in South Africa ushered in a wave of mass protests across the majority of higher learning institutions. The Fallist movement has been opposed by many due to the nature of violence that followed the protests and so called unrainbow -national-like calls the movement stands for. The level of violence prompted critics like Jonathan Jansen, former chancellor of the University of the Free State to declare that SA universities were “finished”.

Those in positions of privilege and power will likely have seen the protests as little more than wasteful and nothing more than organised hooliganism. More astute observers, ones that have been paying attention to the conditions of university campuses and communities beyond the leafy enclaves of Stellenbosch or Hatfield would have known that the student protests of 2015/16 were overdue by many years. While at first glance it might seem that the issues are just about fees and language, the heart of the student activist movements are much deeper. Earlier this year the South African shadow minister for higher education and training, Belinda Bazsoli, penned an article in the Daily Maverick discussing some of the challenges around South African universities.

Bazsoli describes how she and a team of investigators did a comprehensive tour of the country’s institutions of higher learning, and the contrasts they saw shocked them. An easy comparison is one between University of Pretoria and Walter Sisulu University. One the hand you have the UP, nestled in the relatively safe and upmarket enclave of Pretoria’s eastern suburbs. Its grounds are described as park like, its academic and extracurricular facilities are immaculately maintained, it carries an international reputation as a premier research institution and its qualifications, especially ones from its engineering and built environment faculties, are considered a sure ticket to employment. Then on the extreme end of the spectrum lies Walter Sisulu University, formerly known as the University of the Transkei. Walter Sisulu’s rural location poses a challenge to securing students and donors necessary to maintain its operations. This lack of funding is reflected in the poor state of its teaching and accommodation facilities, which are unsafe and not conducive to learning. The university struggles to maintain its staff and foster an alumni network, which makes delivering quality services a difficult task. This has led to the institution losing its accreditation for its formerly prestigious law qualification, effectively casting hundreds of students adrift with little to look forward to but debt and potentially destitution, regardless of the years of effort on their part.

Youth struggles to improve education in South Africa are not new. In mid-June, 40 years before the protests of 2016, another generation of radical young activists stepped out of their own ill-provisioned classrooms to the streets of Soweto seeking justice. Like their Fallist contemporaries they were mostly black South Africans and were also protesting a system of education which was largely decrepit and entirely ambivalent to their needs and human rights. The system they fought, that of “bantu education”, was one which had its inherent inequities consciously worked into it to suit the ideology of the apartheid establishment. While disparities in the quality of education on racial grounds had always been part and parcel of South Africa’s western style school system since its inception in the 19th century, they paled in significance to the dismal prospects that the infamous Bantu Education Act of 1953 stipulated. As Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, one of the chief architects of the system, candidly put it: “The natives must be made to understand from an early age that equality with the European is not for them”.

The act was deliberately designed to make all forthcoming generations of black South Africans capable of little more than the manual labour tasks which the apartheid system condemned them too. Beyond that, it was also intended to foster and entrench already existing inequality by blocking what few avenues still existed which would allow black South Africans to better the positions of them and their communities. To this end the Apartheid government forced the closure of missionary schools operated by local and foreign church groups and made Bantu schooling compulsory. Few preparations were made for this new influx of students into the few government schools set out for this purpose and the system was soon struggling with overcrowding and under staffing, This part of the education system was drastically underfunded compared to schools for whites, and by 1967 the ratio of pupils to teachers at schools designated for black south Africans stood at 58:1. Urgent calls for government attention to these schools were left unheeded even in the decade that South Africa had its highest ever levels of economic growth. Between 1962 and 1971 not a single high school for black South Africans was built, despite a drastic increase in the numbers of black learners in the same time frame.

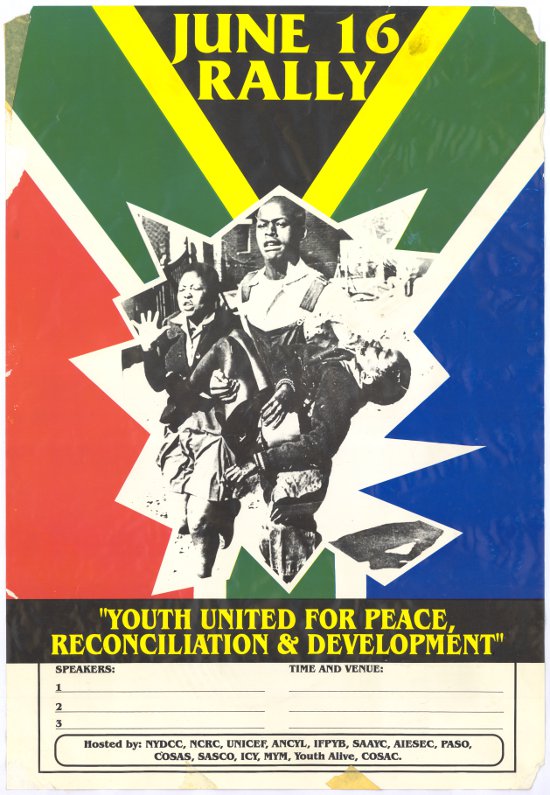

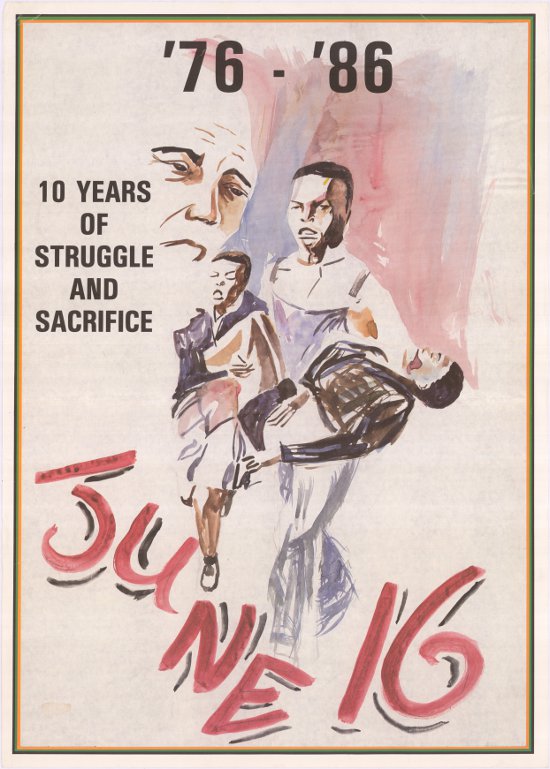

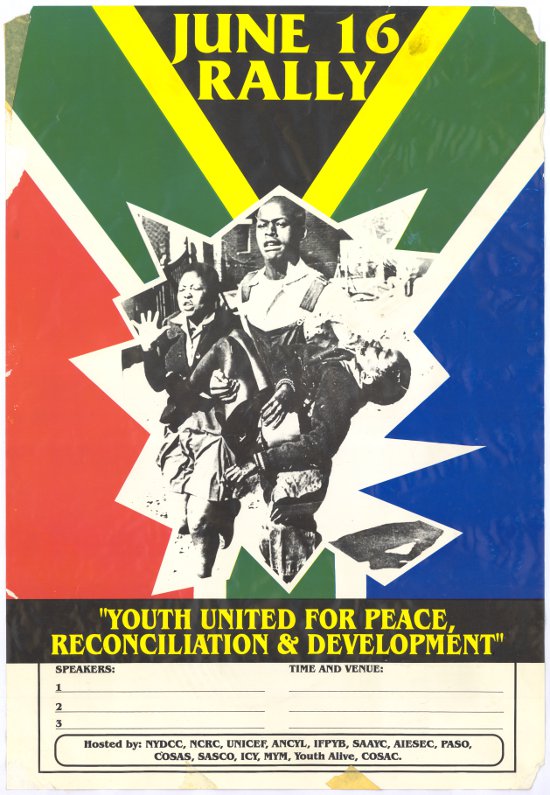

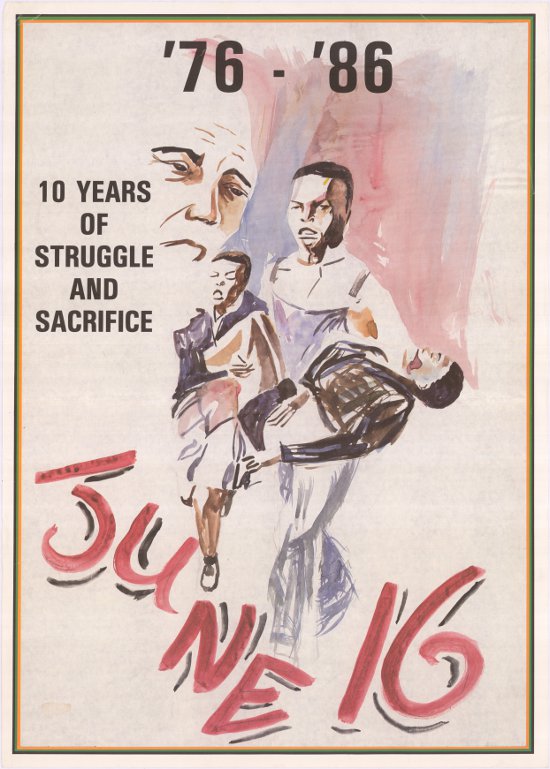

Then in 1975 came the furthest and final provocation. The regime, in total disconnect with the reality on the ground, gave a directive that from now on students in black secondary schools would have to complete half their subjects in Afrikaans if they wished to obtain their certificates. For a student and teacher body who were largely unable to speak and write in the language with the fluency this order required, this was simply the final straw. On June 16, students across Soweto, energized by the new ideology of black consciousness refused to attend school and challenged government security forces face to face. South African Police, imbued with the racial prejudices the system created and with no crowd dispersal methods at their disposal save live ammunition, indiscriminately opened fire. The resulting violence killed over three hundred and injured up to a thousand. The image of a dying Hector Pieterson, one of the first to be shot by police, became an international symbol of the June 16 riots and the brutality inherent in the Apartheid system. It heralded the beginning of international economic and diplomatic sanctions on South Africa and breathed new life into the liberation movements in exile who would be inundated with an entire generation of eager new recruits.

The fall of apartheid and the establishment of the democratic dispensation in South Africa can doubtlessly be traced back to the efforts by the youth on that day. The parallels between the class of 1976 and the Fallists are easy to draw. Yet despite all that has achieved the same struggles are still a daily fact of life for many, starting from primary school all the way to post-graduate. Recently SAHA has had the privilege of assisting a community from Ekurhuleni where residents are growing furious with local government over an inexplicable decision to stop providing a bus fare subsidy for school students. This, combined with a host of other issue was making it difficult for local children to attend school. I was told in no uncertain terms that unless our organization could assist in getting information out of the relevant authorities there would likely be protest action. This brought it home to me what an essential role the FOIP programme can play in activism around access to education and related socio-economic issues facing our society. PAIA gives average citizens access to consultation, accountability and transparency, all features that are instrumental to achieving justice and the reification of the freedom charter upon which our constitution is based. For too long it has been necessary that death and destruction be the preconditions which make government sit up and pay attention to our needs as citizens. With proper use of PAIA we can ensure that this need no longer be the case.